9.4: Método de círculo adicional

- Page ID

- 114845

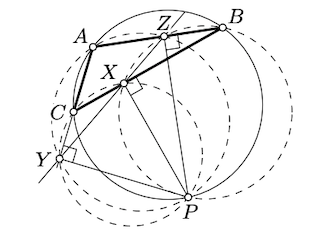

Supongamos que dos acordes\([AA']\) y se\([BB']\) cruzan en el punto\(P\) dentro de su círculo. Que\(X\) sea un punto tal que ambos ángulos\(XAA'\) y\(XBB'\) sean rectos. \((XP) \perp (A'B')\)Demuéstralo.

- Responder

-

Set\(Y = (A'B') \cap (XP)\).

Ambos ángulos\(XAA'\) y\(XBB'\) son rectos; por lo tanto

\(2 \cdot \measuredangle XAA' \equiv 2 \cdot \measuredangle XBB'\).

Por Corolario 9.3.2,\(\square XAPB\) está inscrito. Aplicando de nuevo este teorema obtenemos que

\(2 \cdot \measuredangle AXP \equiv 2 \cdot \measuredangle ABP\).

Dado que\(\square ABA'B'\) está inscrito,

\(2 \cdot \measuredangle ABB' \equiv 2 \cdot \measuredangle AA'B'\).

De ello se deduce que

\(2 \cdot \measuredangle AXY \equiv 2 \cdot \measuredangle AA'Y\).

Por el mismo teorema\(\square XAYA'\) se inscribe, y por lo tanto,

\(2 \cdot \measuredangle XAA' \equiv 2 \cdot \measuredangle XYA'\).

Ya que\(\angle XAA'\) es correcto, así es\(\angle XYA'\). Eso es\((XP) \perp (A'B')\).

Encuentra una inexactitud en la solución de Problema\(\PageIndex{1}\) e intenta solucionarlo.

- Pista

-

Hay que demostrar que las líneas\((A'B')\) y no\((XP)\) son paralelas, de lo contrario la primera línea en la prueba no tiene sentido.

Además, se utilizaron implícitamente las siguientes identidades:

\(2 \cdot \measuredangle AXP \equiv 2 \cdot \measuredangle AXY\),\(2 \cdot \measuredangle ABP \equiv 2 \cdot \measuredangle ABB'\),\(2 \cdot \measuredangle AA'B' \equiv 2 \cdot \measuredangle AA'Y\).

El método utilizado en la solución se denomina método de círculo adicional, ya que los circuncírculos de los\(XAPB\) cuadrángulos y\(XAPB\) superiores pueden considerarse como construcciones adicionales.

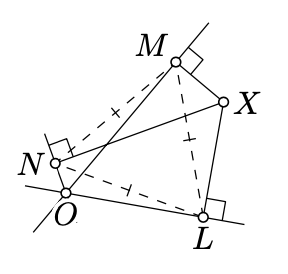

Supongamos tres líneas\(\ell, m\), y se\(n\) cruzan en el punto\(O\) y forman seis ángulos iguales en\(O\). Seamos\(X\) un punto distinto de\(O\). Dejar\(L, M\), y\(N\) denotar los puntos del pie de las perpendiculares a\(X\) partir de\(\ell, m\), y\(n\) respectivamente. Mostrar que\(\triangle LMN\) es equilátero.

- Pista

-

Por Corolario 9.3.1, los puntos\(L, M\), y\(N\) se encuentran en el círculo\(\Gamma\) con diámetro\([OX]\). Queda por aplicar el Teorema 9.2.1 para el círculo\(\Gamma\) y dos ángulos inscritos con vértice en\(O\).

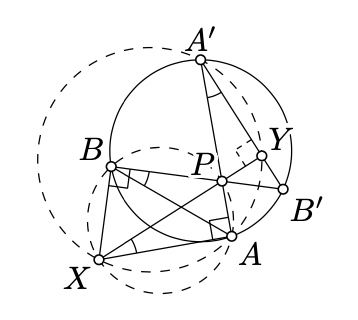

Supongamos que un punto\(P\) se encuentra en el circuncírculo del triángulo\(ABC\). Mostrar que tres puntos de pie de\(P\) en las líneas\((AB), (BC)\), y\((CA)\) se encuentran en una línea. (Esta línea se llama la línea Simson de\(P\)).

- Pista

-

Dejar\(X, Y\), y\(Z\) denotar los puntos del pie de\(P\) on\((BC), (CA)\), y\((AB)\) respectivamente. Demostrar que\(\square AZPY\)\(\square BXPZ\),\(\square CYPX\),, y\(\square ABCP\) están inscritos. Utilízalo para demostrar que

\(\begin{array} {rcl} {2 \cdot \measuredangle CXY \equiv 2 \cdot \measuredangle CPY} & \ \ \ \ & {2 \cdot \measuredangle BXZ \equiv 2 \cdot \measuredangle BPZ,} \\ {2 \cdot \measuredangle YAZ \equiv 2 \cdot \measuredangle YPZ} & \ \ \ \ & {2 \cdot \measuredangle CAB \equiv 2 \cdot \measuredangle CPB.} \end{array}\)

Concluir eso\(2 \cdot \measuredangle CXY \equiv 2 \cdot \measuredangle BXZ\) y por lo tanto\(X, Y\), y\(Z\) mentir en una línea.