13.2: Inradio del triángulo h

- Page ID

- 114326

El inradio de cualquier triángulo h es menor que\(\dfrac{1}{2} \cdot \ln3\).

- Prueba

-

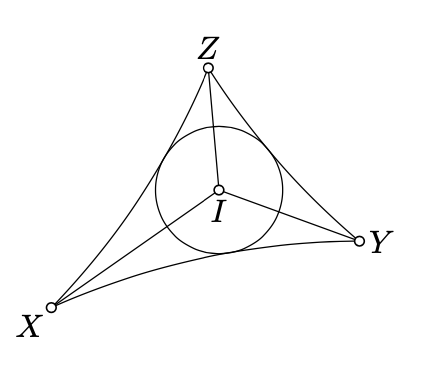

Dejar\(I\) y\(r\) ser el h-incenter y h-inradius de\(\triangle_hXYZ\).

Tenga en cuenta que los ángulos h\(XIY\),\(YIZ\) y\(ZIX\) tienen el mismo signo. Sin pérdida de generalidad, podemos suponer que todos ellos son positivos y por lo tanto

\(\measuredangle_hXIY+ \measuredangle_hYIZ+ \measuredangle_hZIX=2 \cdot \pi\)

Podemos suponer que\(\measuredangle_hXIY \ge \dfrac{2}{3} \cdot \pi\); si no relabel\(X\),\(Y\), y\(Z\).

Dado que\(r\) es la distancia h de\(I\) a\((XY)_h\), la Proposición 13.1.1 implica que

\(\begin{array} {rcl} {r} & < & {\dfrac{1}{2} \cdot \ln \dfrac{1 + \cos \dfrac{\pi}{3}}{1 - \cos \dfrac{\pi}{3}}} \\ {} & = & {\dfrac{1}{2} \cdot \ln \dfrac{1 + \dfrac{1}{2}}{1 - \dfrac{1}{2}}} \\ {} & = & {\dfrac{1}{2} \cdot \ln 3.} \end{array}\)

Dejar\(\square_h ABCD\) ser un cuadriángulo en el plano h tal que los ángulos h en\(A\),\(B\), y\(C\) son correctos y\(AB_h=BC_h\). Encuentra el límite superior óptimo para\(AB_h\).

- Insinuación

-

Tenga en cuenta que el ángulo de prarllelismo de\(B\) a\((CD)_h\) es mayor que\(\dfrac{\pi}{4}\), y converge a\(\dfrac{\pi}{4}\) como\(CD_h \to \infty\).

Aplicando la Proposición 13.1.1, obtenemos que

\(BC_h < \dfrac{1}{2} \cdot \ln \dfrac{1 + \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}}}{1 - \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}}} = \ln (1 + \sqrt{2}).\)

El lado derecho es el límite de\(BC_h\) si\(CD_h \to \infty\). Por lo tanto,\(\ln (1 + \sqrt{2})\) es el límite superior óptimo.