18.5: Argumento y coordenadas polares

- Page ID

- 114782

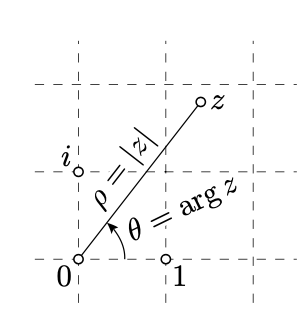

Como antes, asumimos que\(O\) y\(E\) son los puntos con coordenadas complejas\(0\) y\(1\) respectivamente.

Dejar\(Z\) ser un punto de forma distinta\(O\). Establecer\(\rho=OZ\) y\(\theta=\measuredangle EOZ\). El par\((\rho,\theta)\) se llama las coordenadas polares de\(Z\).

Si\(z\) es la compleja coordenada de\(Z\), entonces\(\rho=|z|\). Al valor\(\theta\) se le llama el argumento de\(z\) (brevemente,\(\theta=\arg z\)). En este caso,

\(z=\rho\cdot e^{i\cdot\theta}=\rho\cdot(\cos\theta+i\cdot\sin\theta).\)

Tenga en cuenta que

\(\arg (z\cdot w) \equiv \arg z+\arg w\)

y

\(\arg \tfrac z w \equiv \arg z-\arg w\)

si\(z \ne 0\) y\(w \ne 0\). En particular, si\(Z\)\(V\),\(W\) son puntos con coordenadas complejas\(z\)\(v\), y\(w\) respectivamente, entonces

\[\begin{aligned} \measuredangle VZW &=\arg\left(\frac{w-z}{v-z}\right)\equiv \\ &\equiv \arg(w-z)-\arg(v-z) \end{aligned}\]

si\(\measuredangle VZW\) se define.

Usa la fórmula 18.5.1 para demostrar que

\(\measuredangle ZVW+\measuredangle VWZ+\measuredangle WZV\equiv \pi\)

para cualquiera\(\triangle ZVW\) en el plano euclidiano.

- Insinuación

-

Dejar\(z, v\), y\(w\) denotar las coordenadas complejas de\(Z, V\), y\(W\) respectivamente. Entonces

\(\begin{array} {rcl} {\measuredangle ZVW + \measuredangle VWZ + \measuredangle WZV} & \equiv & {\arg \dfrac{w - v}{z- v} + \arg \dfrac{z-w}{v-w} + \arg \dfrac{v-z}{w-z} \equiv} \\ {} & \equiv & {\arg \dfrac{(w - v) \cdot (z - w) \cdot (v -z)}{(z - v) \cdot (v - w) \cdot (w - z)} \equiv} \\ {} & \equiv & {\arg (-1) \equiv \pi} \end{array}\)

Supongamos que los puntos\(O\)\(E\)\(V\),\(W\),,, y\(Z\) tienen coordenadas complejas\(0\)\(1\),,\(v\),\(w\), y\(z=v\cdot w\) respectivamente. Demostrar que

\(\triangle OEV\sim \triangle OWZ.\)

- Insinuación

-

Tenga en cuenta y use eso\(\measuredangle EOV = \measuredangle WOZ = \arg v\) y\(\dfrac{OW}{OZ} = \dfrac{OZ}{OW} = |v|\).

El siguiente teorema es una reformulación del Corolario 9.3.2 que utiliza coordenadas complejas.

Dejar\(\square UVWZ\) ser un cuadriángulo y\(u\)\(v\),\(w\),, y\(z\) ser las complejas coordenadas de sus vértices. Entonces\(\square UVWZ\) se inscribe si y sólo si el número

\(\dfrac{(v-u)\cdot(z-w)}{(v-w)\cdot(z-u)}\)

es real.

El valor\(\dfrac{(v-u)\cdot(w-z)}{(v-w)\cdot(z-u)}\) se denomina relación cruzada compleja de\(u\),\(w\),\(v\), y\(z\); se denotará por\((u,w;v,z)\).

Observe que el número complejo\(z\ne 0\) es real si y sólo si\(\arg z=0\) o\(\pi\); en otras palabras,\(2\cdot\arg z\equiv 0\).

Utilice esta observación para demostrar que el Teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\) es efectivamente una reformulación del Corolario 9.3.2.

- Insinuación

-

Tenga en cuenta que

\(\arg \dfrac{(v-u) \cdot (z-w)}{(v -w) \cdot (z -u)} \equiv \arg \dfrac{v - u}{z - u} + \arg \dfrac{z- w}{v -w} = \measuredangle ZUV + \measuredangle VWZ.\)

La declaración sigue ya que el valor\(\dfrac{(v - u) \cdot (x - w)}{(v - w) \cdot (z - u)}\) es real si y solo si

\(2 \cdot \arg \dfrac{(v - u) \cdot (z - w)}{(v - w) \cdot (z - u)} \equiv 0.\)