18.6: Método de coordenadas complejas

- Page ID

- 114754

El siguiente problema ilustra el método de coordenadas complejas.

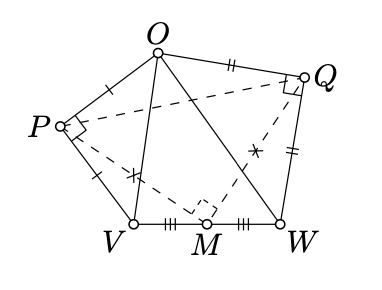

Dejar\(\triangle OPV\) y\(\triangle OQW\) ser isósceles triángulos rectos tales que

\(\measuredangle VPO = \measuredangle OQW=\dfrac{\pi}{2}\)

y\(M\) ser el punto medio de\([VW]\). Supongamos\(P\)\(Q\),, y\(M\) son puntos distintos. Mostrar que\(\triangle PMQ\) es un triángulo rectángulo isósceles.

- Solución

-

Elija las coordenadas complejas de manera que ese\(O\) sea el origen; denote por\(v, w, p, q, m\) las coordenadas complejas de los puntos restantes respectivamente.

Dado que\(\triangle OPV\) y\(\triangle OQW\) son isósceles y\(\measuredangle VPO=\measuredangle OQW=\dfrac{\pi}{2}\), 18.3.2 y 18.5.1 implican que

\(\begin{aligned} v-p&=i\cdot p, & q-w&=i\cdot q.\end{aligned}\)

Por lo tanto

\(\begin{aligned} m&=\tfrac12\cdot(v+w)= \\ &=\tfrac{1+i}2\cdot p+\tfrac{1-i}2\cdot q.\end{aligned}\)

Por cálculos sencillos, obtenemos que

\(p-m=i\cdot (q-m).\)

En particular,\(|p-m|=|q-m|\) y\(\arg\dfrac{p-m}{q-m}=\dfrac{\pi}{2}\); es decir,\(PM=QM\) y\(\measuredangle QMP =\dfrac{\pi}{2}\).

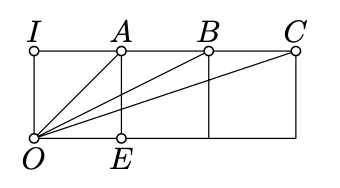

Considera tres cuadrados con lados comunes como en el diagrama. Utilice el método de coordenadas complejas para mostrar que

\(\measuredangle EOA+\measuredangle EOB+\measuredangle EOC=\pm\dfrac{\pi}{2}.\)

- Sugerencia

-

Podemos elegir las coordenadas complejas para que los puntos\(O, E, A, B\), y\(C\) tengan coordenadas\(0, 1, 1 + i, 2 + i\), y\(3 + i\) respectivamente.

Establecer\(\measuredangle EOA = \alpha\),\(\measuredangle EOB = \beta\), y\(\measuredangle EOC = \gamma\). Tenga en cuenta que

\(\begin{array} {rcl} {\alpha + \beta + \gamma} & \equiv & {\arg (1 + i) + \arg (2 + i) + \arg (3 + i) \equiv} \\ {} & \equiv & {\arg [(1 + i) \cdot (2 + i) \cdot (3 + i)] \equiv \arg [10 \cdot i] = \dfrac{\pi}{2}} \end{array}\)

Obsérvese que estos tres ángulos son agudos y concluyan que\(\alpha + \beta + \gamma = \dfrac{\pi}{2}\).

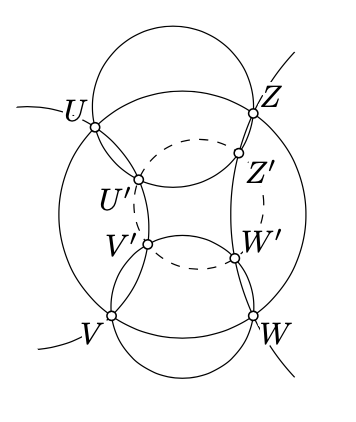

Verifique la siguiente identidad con seis relaciones cruzadas complejas:

\((u,w;v,z)\cdot(u',w';v',z')=\frac{(v,w';v',w)\cdot(z,u';z',u)}{(u,v';u',v)\cdot(w,z';w',z)}.\)

Utilízala junto con el Teorema 18.5.1 para probar que si\(\square UVWZ\)\(\square UVV'U'\)\(\square VWW'V'\)\(\square WZZ'W'\),,,, y\(\square ZUU'Z'\) están inscritos, entonces también\(\square U'V'W'Z'\) se inscribe.

- Sugerencia

-

La identidad se puede verificar mediante cálculos sencillos.

Por Teorema 18.5.1, cinco de seis relaciones cruzadas en la esta identidad son reales. Por lo tanto, así es la sexta relación cruzada; queda por aplicar nuevamente el teorema.

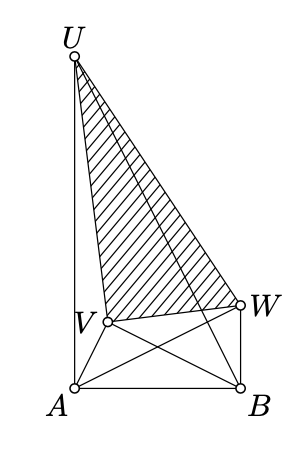

Supongamos que apunta\(U\),\(V\) y\(W\) se encuentran en un lado de la línea\((AB)\) y\(\triangle UAB\sim \triangle BVA \sim \triangle ABW\). Denote por\(a\)\(b\),\(u\),\(v\),, y\(w\) las complejas coordenadas de\(A\),\(B\),\(U\),\(V\), y\(W\) respectivamente.

- \(\dfrac{u-a}{b-a}=\dfrac{b-v}{a-v}=\dfrac{a-b}{w-b}=\dfrac{u-v}{w-v}\)Demuéstralo.

- Concluir eso\(\triangle UAB\sim \triangle BVA \sim \triangle ABW\sim \triangle UVW\).

- Sugerencia

-

Usa 3.7 y 3.10 para mostrar eso\(\angle UAB, \angle BVA\), y\(\angle ABW\) tener el mismo signo. Tenga en cuenta que por SAS tenemos que

\(\dfrac{AU}{AB} = \dfrac{VB}{VA} = \dfrac{BA}{BW}\)y\(\measuredangle UAB = \measuredangle BVA =\measuredangle ABW.\)

El último significa que\(|\dfrac{u - a}{b - a}| = |\dfrac{b - v}{a - v}| = |\dfrac{a - b}{w - b}|\), y\(\arg \dfrac{b - a}{u - a} = \arg \dfrac{a - b}{w - b}\). Implica las dos primeras igualdades en

\[\dfrac{b - a}{u - a} = \dfrac{a - v}{b - v} = \dfrac{w - b}{a -b} = \dfrac{w - v}{u - v}.\]

la última igualdad se mantiene desde

\(\dfrac{(b - a) + (a -v) + (w - b)}{(u - a) + (b - v) + (a -b)} = \dfrac{w - v}{u - v}.\)

Para probar (b), reescribir 18.6.1 usando ángulos y distancias entre los puntos y aplicar SAS.