20.5: Área de rectángulos sólidos

- Page ID

- 114518

Un rectángulo sólido con lados\(a\) y\(b\) tiene área\(a\cdot b\).

- Prueba

-

Supongamos que\(\mathcal{R}_{a,b}\) denota el rectángulo sólido con lados\(a\) y\(b\). Set

\(s(a,b)=\text{area } \mathcal{R}_{a,b}.\)

Por definición de área,\(s(1,1)=\text{area }(\mathcal{K})=1\). Es decir, se sostiene la primera identidad en el lema algebraico.

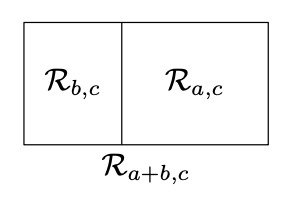

Tenga en cuenta que el rectángulo se\(\mathcal{R}_{a+b,c}\) puede subdividir en dos rectángulos congruentes con\(\mathcal{R}_{a,c}\) y\(\mathcal{R}_{b,c}\). Por lo tanto, por la Proposición 20.4.2,

\(\text{area }\mathcal{R}_{a+b,c}=\text{area } \mathcal{R}_{a,c}+\text{area } \mathcal{R}_{b,c}\)

Es decir, se mantiene la segunda identidad en el lema algebraico. La prueba de la tercera identidad es análoga.

Queda por aplicar el lema algebraico.

Supongamos que una función\(s\) devuelve un número real no negativo\(s(a,b)\) para cualquier par de números reales positivos\((a,b)\) y satisface las siguientes identidades:

\(\begin{aligned} s(1,1)&=1; \\ s(a,b+c)&=s(a,b)+s(a,c) \\ s(a+b,c)&=s(a,c)+s(b,c)\end{aligned}\)

para cualquier\(a,b,c>0\). Entonces

\(s(a,b)=a\cdot b\)

para cualquier\(a,b>0\).

La prueba es similar a la prueba de Lemma 14.4.1.

- Prueba

-

Tenga en cuenta que si\(a>a'\) y\(b>b'\) luego

\[s(a,b)\ge s(a',b').\]

En efecto, dado que\(s\) devuelve números no negativos, obtenemos que

\(\begin{aligned} s(a,b)&=s(a',b)+s(a-a',b)\ge \\ &\ge s(a',b)= \\ &\ge s(a',b')+s(a',b-b')\ge \\ &\ge s(a',b').\end{aligned}\)

Aplicando la segunda y tercera identidad pocas veces lo conseguimos

\(\begin{aligned} s(a,m\cdot b)=s(m\cdot a,b)=m\cdot s(a,b)\end{aligned}\)

para cualquier entero positivo\(m\). Por lo tanto

\(\begin{aligned} s(\tfrac kl,\tfrac mn)&=k \cdot s(\tfrac 1l,\tfrac mn)= \\ &=k\cdot m \cdot s(\tfrac 1l,\tfrac 1n)= \\ &=k\cdot m\cdot \tfrac 1l\cdot s(1, \tfrac 1n)= \\ &=k\cdot m\cdot \tfrac 1l\cdot \tfrac 1n\cdot s(1,1)= \\ &=\tfrac kl\cdot\tfrac mn\end{aligned}\)

para cualquier número entero positivo\(k\),\(l\),\(m\), y\(n\). Es decir, la identidad necesaria se mantiene para cualquier par de números racionales\(a=\tfrac kl\) y\(b=\tfrac mn\).

Argumentar por contradicción, asumir\(s(a,b)\ne a\cdot b\) para algún par de números reales positivos\((a,b)\). Consideraremos dos casos:\(s(a,b)> a\cdot b\) y\(s(a,b)< a\cdot b\).

Si\(s(a,b)> a\cdot b\), podemos elegir un entero positivo\(n\) tal que

\[s(a,b)> (a+\tfrac1n)\cdot (b+\tfrac1n).\]

Establecer\(k=\lfloor a\cdot n \rfloor+1\) y\(m=\lfloor b\cdot n \rfloor+1\); equivalentemente,\(k\) y\(m\) son enteros positivos de tal manera que

\(a< \tfrac kn\le a+\tfrac1n \quad\text{and}\quad b<\tfrac mn\le b+\tfrac1n.\)

Por 20.5.1, obtenemos eso

\(\begin{aligned} s(a,b)&\le s(\tfrac kn,\tfrac mn)= \\ &=\tfrac kn\cdot\tfrac mn\le \\ &\le (a+\tfrac1n)\cdot(b+\tfrac1n),\end{aligned}\)

lo que contradice 20.5.2.

El caso\(s(a,b)< a\cdot b\) es similar. Fijar un entero positivo\(n\) tal que\(a>\tfrac1n\),\(b>\tfrac1n\), y

\[s(a,b)< (a-\tfrac1n)\cdot (b-\tfrac1n).\]

Set\(k=\lceil a\cdot n \rceil-1\) y\(m=\lceil b\cdot n \rceil-1\); es decir,

\(a> \tfrac kn\ge a-\tfrac1n \quad\text{and}\quad b>\tfrac mn\ge b-\tfrac1n.\)

Aplicando 20.5.1 de nuevo, obtenemos que

\(\begin{aligned} s(a,b)&\ge s(\tfrac kn,\tfrac mn)= \\ &=\tfrac kn\cdot\tfrac mn\ge \\ &\ge (a-\tfrac1n)\cdot(b-\tfrac1n),\end{aligned}\)

lo que contradice 20.5.3.