7.2: Círculos

- Page ID

- 114760

El círculo es una de las figuras geométricas más frecuentes. Ruedas, anillos, discos fonográficos, relojes, monedas son solo algunos ejemplos de objetos comunes con forma circular. El círculo tiene muchas aplicaciones en la construcción de maquinaria y en el diseño arquitectónico y ornamental.

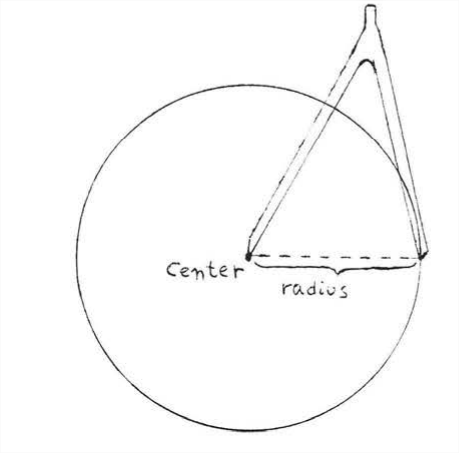

Para dibujar un círculo utilizamos un instrumento llamado brújula (Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\)). La brújula consta de dos brazos, uno que termina en una punta metálica afilada y el otro unido a un lápiz. Dibujamos el círculo girando el lápiz mientras se sujeta la punta metálica para que no se mueva, La posición de la punta metálica se llama el centro del círculo. La distancia entre el centro y la punta del lápiz se llama el radio del círculo, el radio sigue siendo el mismo que se dibuja el círculo.

El método de construcción de un círculo sugiere la siguiente definición:

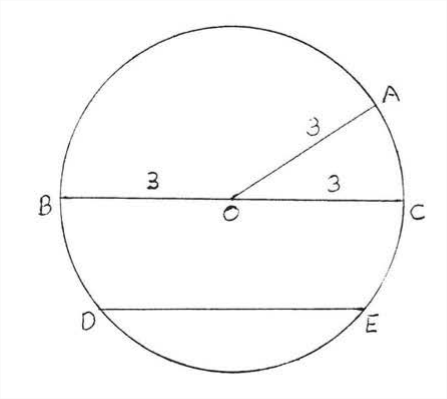

Un círculo es una figura que consta de todos los puntos que están a una distancia dada de un punto fijo llamado centro. Por ejemplo, el círculo de la Figura 2 consiste en todos los puntos que están a una distancia de 3 desde el centro 0. El radio es la distancia de cualquier punto del círculo desde el centro.

El círculo en la Figura\(\PageIndex{2}\) tiene radio 2. El término radio también se usa para denotar cualquiera de los segmentos de línea desde un punto en el círculo hasta el centro. En la Figura\(\PageIndex{2}\), cada uno de los segmentos de línea\(OA, OB\), y\(OC\) es un radio. De la definición de círculo se deduce que todos los radios de un círculo son iguales. Así que en\(\PageIndex{2}\) la Figura los tres radios\(OA, OB\), y\(OC\) son todos iguales a 3.

Un círculo suele llamarse por su centro. El círculo en la Figura\(\PageIndex{2}\) se llama círculo\(O\).

Un acorde es un segmento de línea que une dos puntos en un círculo. En Figura\(\PageIndex{2}\),\(DE\) es un acorde. Un diámetro es una cuerda que pasa por el centro. \ (BC es un diámetro. Un diámetro es siempre el doble de la longitud de un radio ya que consta de dos radios. Cualquier diámetro del círculo 0 es igual a 6. Todos los diámetros de un círculo son iguales.

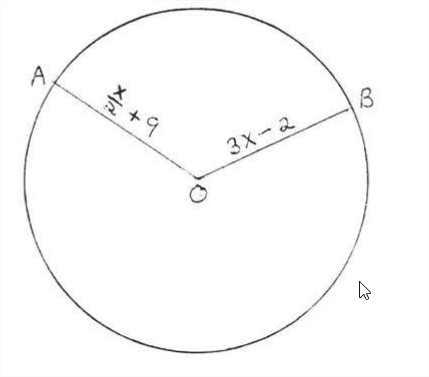

Encuentra el radio y diámetro y diámetro.

Solución

Todos los radios son iguales

\ [\ comenzar {alineado}

O A &=O B\\

\ frac {x} {2} +9 &=3 x-2\\

(2)\ izquierda (\ frac {x} {2} +9\ derecha) &= (3 x-2) (2)\\

x+18 &=6 x-4\\

22 &=5 x\\

x &=\ frac {22} {5} =4.4

\ end {alineado}\]

Comprobar:

\(OA = OB\)

\ [\ begin {array} {r|l}

\ frac {x} {2} +9 y 3 x-2\\

\ frac {4.4} {2} +9 y 3 (4.4) -2\\

2.2+9 y 13.2-2\\

11.2 y 11.2

\ end {array}\]

Por lo tanto el radio\(OA = OB\) = = 11.2 y el diámetro = 2 (11.2) =22.4.

Respuesta: radio =11.2, diámetro =22.4.

Los siguientes tres teoremas muestran que un diámetro de un círculo y la bisectriz perpendicular de una cuerda en un círculo son en realidad lo mismo.

Un diámetro perpendicular a una cuerda biseca la cuerda.

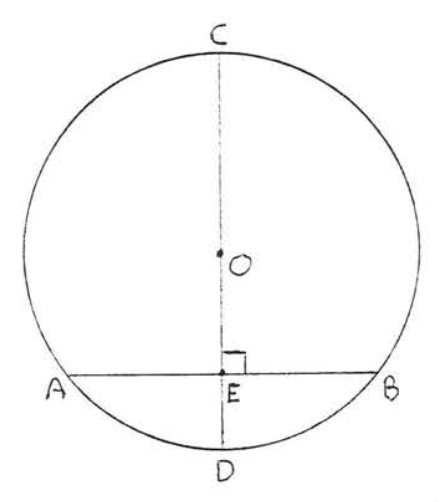

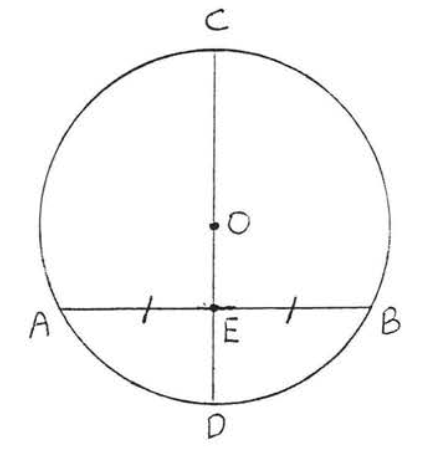

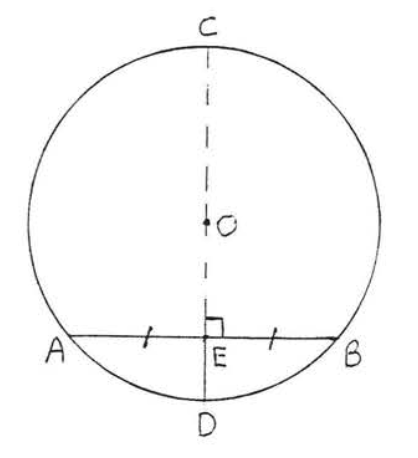

En la Figura\(\PageIndex{3}\), si\(AB \perp CD\) entonces\(AE = EB\).

- Prueba

-

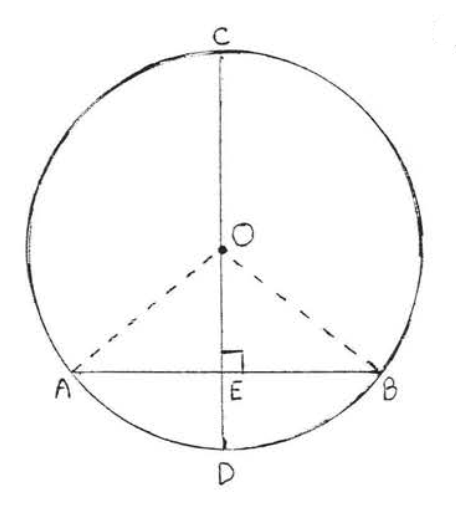

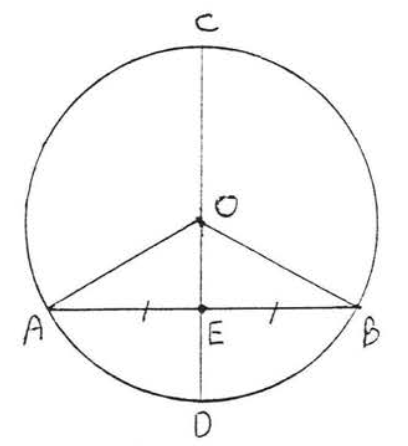

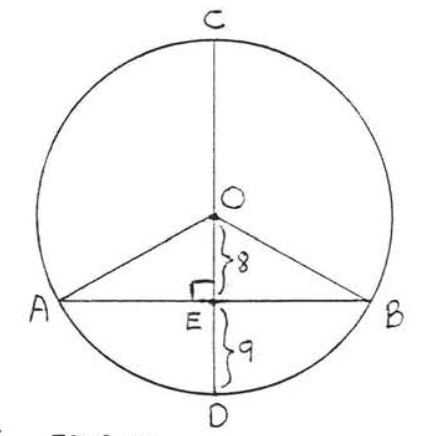

Figura\(\PageIndex{4}\): Dibujar\(OA\) y\(OB\). Dibujar\(OA\) y\(OB\) (Figura\(\PageIndex{4}\)). \(OA = OB\)porque todos los radios de un círculo son iguales. \(OE = OE\)por identidad. Por lo tanto\(\triangle ACE \cong \triangle BOE\) por Hyp-Leg = Hyp-Leg. De ahí\(AE = BE\) porque son lados correspondientes de triángulos congruentes.

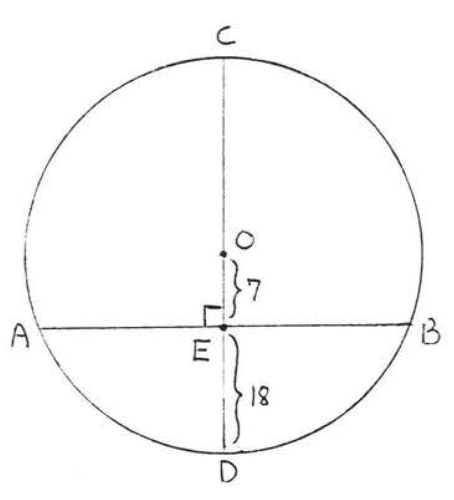

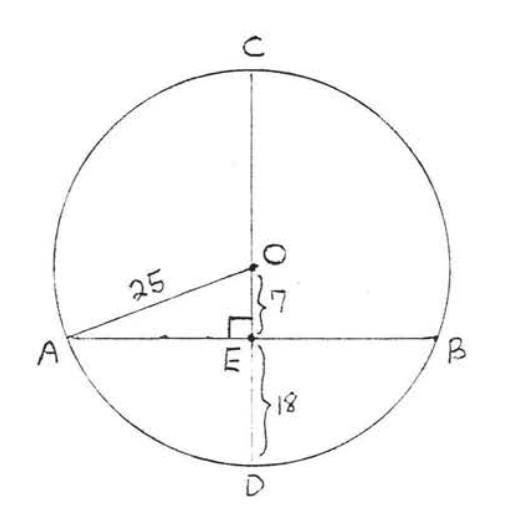

Encuentra\(AB\):

Solución

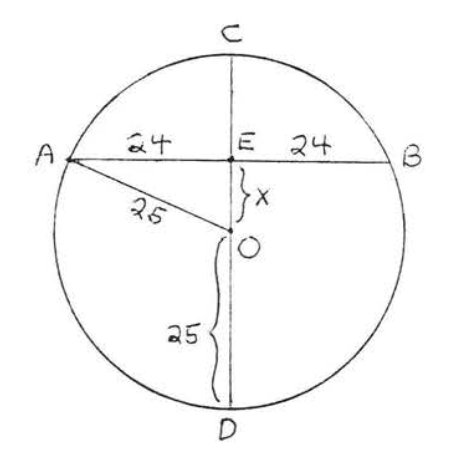

Dibujar\(OA\) (Figura\(\PageIndex{5}\)). \(OA = \text{radius} = OD = 18 + 7 = 25\). \(\triangle AOE\)es un triángulo rectángulo y por lo tanto podemos usar el teorema de Pitágoras para encontrar\(AE\):

\(\begin{array} {rcl} {\text{AE}^2+\text{CE}^2} & = & {\text{CA}^2} \\ {\text{AE}^2 + 7^2} & = & {25^2} \\ {\text{AE}^2 + 49} & = & {625} \\ {\text{AE}^2} & = & {576} \\ {\text{AE}} & = & {24} \end{array}\)

Por teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\),\(EB = AE = 24\) entonces\(AB = AE + EB = 24 + 24 = 48\).

Respuesta:\(AB = 48\).

Un diámetro que biseca una cuerda que no es un diámetro es perpendicular a ella.

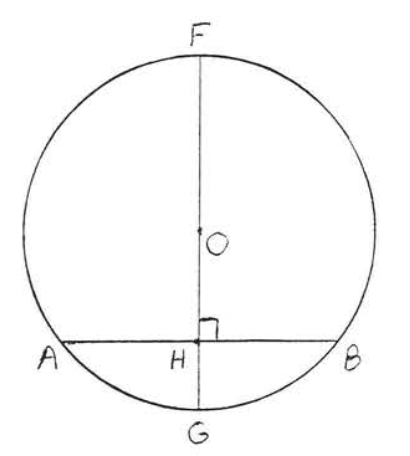

En la Figura\(\PageIndex{6}\), si\(AE = EB\) entonces\(AB \perp CD\).

- Prueba

-

Figura\(\PageIndex{7}\): Dibujar\(OA\) y\(OB\). Dibujar\(OA\) y\(OB\) (Figura\(\PageIndex{7}\)). \(OA = OB\)porque todos los radios son iguales,\(OE = OE\) (identidad) y\(AE = EB\) (dados). Por lo tanto\(\triangle AOE \cong \triangle BOE\) por\(SSS = SSS\). Por lo tanto\(\triangle AEO = \triangle BEO\). Ya que\(\angle AEO\) y también\(\angle BEO\) son complementarios debemos tener también\(\angle AEO = \angle BEO = 90^{\circ}\), que es lo que teníamos que probar.

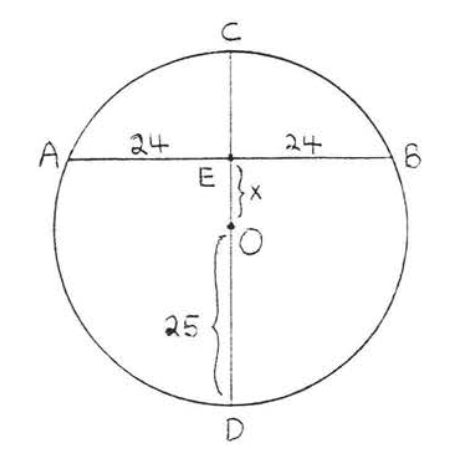

Encuentra\(x\):

Solución

Dibujar\(OA\) (Figura\(PageIndex{8}\)). \(OA = \text{radius} = OD = 25\). Según el teorema\(\PageIndex{2}\),\(AB \perp CD\). Por lo tanto\(\triangle AOE\) es un triángulo rectángulo, y podemos usar el teorema de Pitágoras para encontrar\(x\):

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {\text{OE}^2 + \text{AE}^2} & = & {\text{OA}^2} \\ {x^2 + 24^2} & = & {25^2} \\ {x^2 + 576} & = & {625} \\ {x^2} & = & {49} \\ {x} & = & {7} \end{array}\]

Respuesta:\(x = 7\).

La bisectriz perpendicular de una cuerda debe pasar por el centro del círculo (es decir, es un diámetro).

En Figura\(\PageIndex{9}\), si\(CD \perp AB\) y\(AE = EB\) luego\(O\) debe acostarse\(CD\).

- Prueba

-

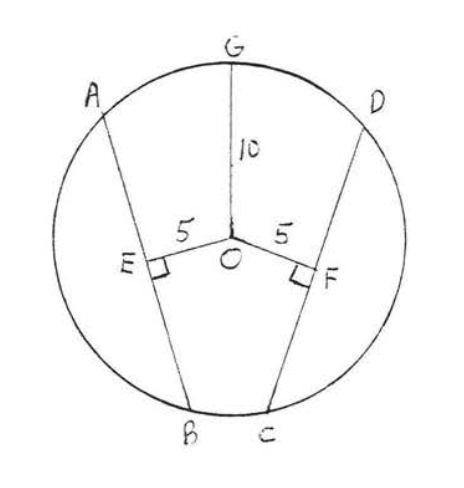

Figura\(\PageIndex{10}\): Dibujar\(FG\) a través de\(O\) perpendicular a\(AB\). Dibuje un diámetro\(FG\) a través de\(O\) perpendicular a\(AB\) at\(H\) (Figura\(\PageIndex{10}\)). Entonces según el Teorema se\(\PageIndex{1}\)\(H\) debe bisectar\(AB\). De ahí\(H\) y\(E\) son el mismo punto y\(FG\) y\(CD\) son la misma línea. Entonces\(O\) yace en\(CD\). Esto completa la prueba.

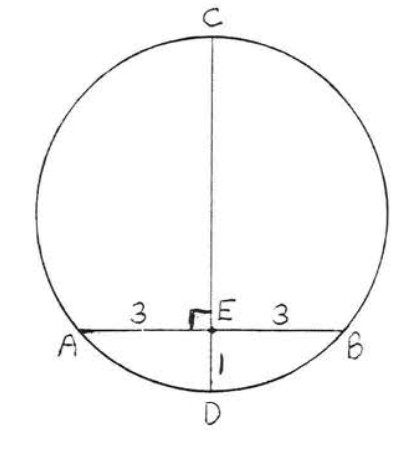

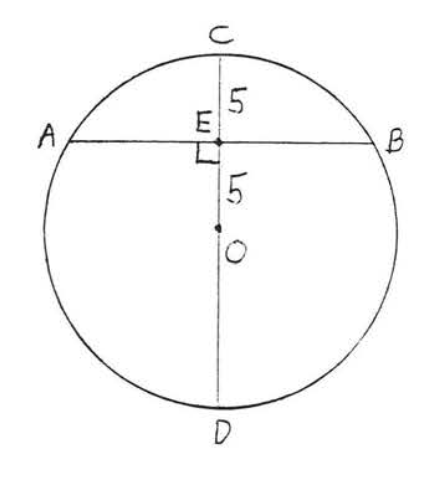

Encuentra el radio del círculo:

Solución

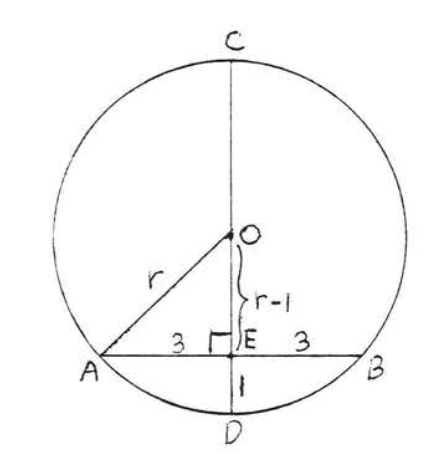

Según el Teorema\(\PageIndex{3}\),\(O\) hay que mentir sobre\(CD\). Dibujar\(OA\) (Figura\(\PageIndex{11}\)). Deja\(r\) ser el radio. Entonces\(OA = OD = r\) y\(OE = r - 1\). Para encontrar\(r\) aplicamos el teorema de Pitágoras al triángulo rectángulo\(AOE\):

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {\text{AE}^2 + \text{OE}^2} & = & {\text{OA}^2} \\ {3^2 + (r - 1)^2} & = & {r^2} \\ {9 + r^2 - 2r + 1} & = & {r^2} \\ {10} & = & {2r} \\ {5} & = & {r} \end{array}\]

Respuesta:\(r = 5\).

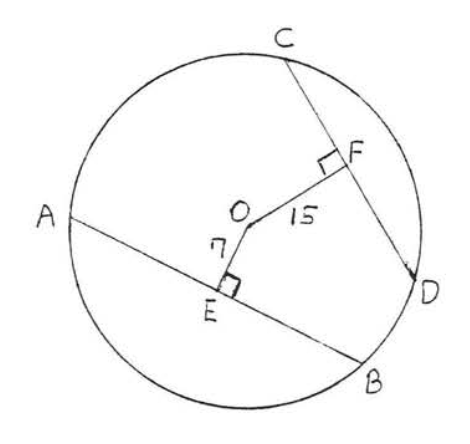

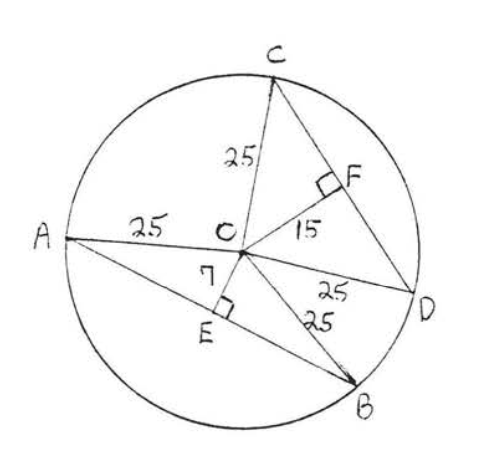

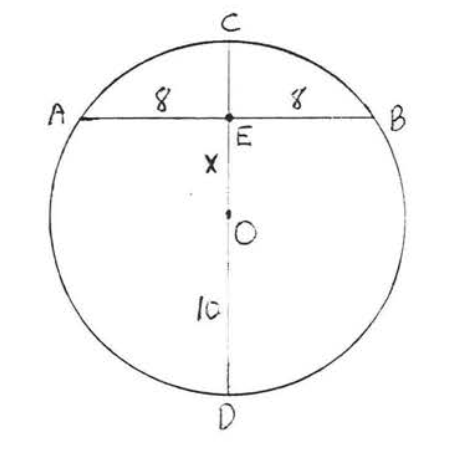

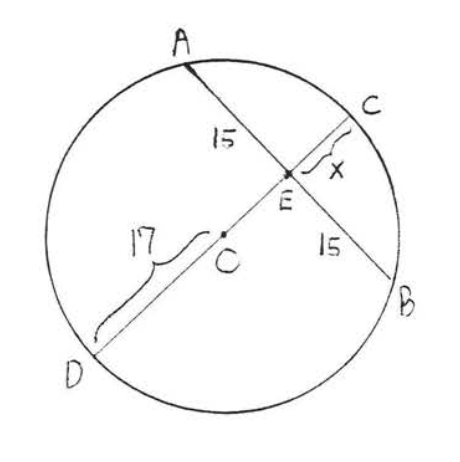

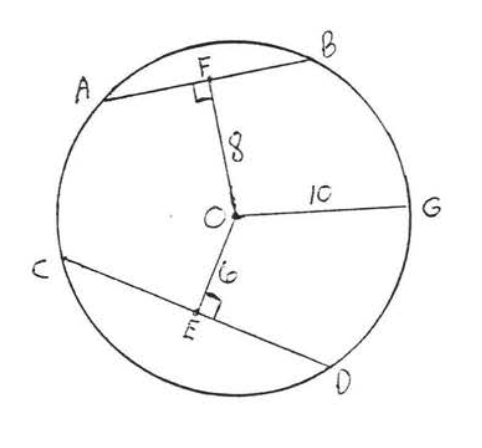

Encuentra qué acorde,\(AB\) o\(CD\), es mayor si el radio del círculo es 25:

Solución

Dibujar\(OA, OB, OC\) y\(OD\) (Figura\(\PageIndex{12}\)). Cada uno es un radio e igual a 25. Utilizamos el teorema de Pitágoras, aplicado al triángulo rectángulo\(AOE\), para encontrar\(AE\):

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {\text{AE}^2 + \text{OE}^2} & = & {\text{OA}^2} \\ {\text{AE}^2 + 7^2} & = & {25^2} \\ {\text{AE}^2 + 49} & = & {625} \\ {\text{AE}^2} & = & {576} \\ {\text{AE}} & = & {24} \end{array}\]

Dado que las\(OE\) bisectas perpendiculares\(AB\) (Teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\))\(BE = AE = 24\) y así\(AB = AE + BE = 24 + 24 = 48\).

De igual manera, para encontrar\(CF\), aplicamos el teorema de Pitágoras al triángulo rectángulo\(COF\):

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {\text{CF}^2 + \text{OF}^2} & = & {\text{OC}^2} \\ {\text{CF}^2 + 15^2} & = & {25^2} \\ {\text{CF}^2 + 225} & = & {625} \\ {\text{CF}^2} & = & {400} \\ {\text{CF}} & = & {20} \end{array}\]

Nuevamente, a partir del Teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\), conocemos\(OF\) bisectas\(CD\), de ahí\(DF = CF = 20\) y\(CD = 40\).

Respuesta:\(AB = 48\),\(CD = 40\),\(AB\) es mayor que\(CD\).

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{5}\) sugiere el siguiente Teorema (que declaramos sin pruebas):

La longitud de una cuerda está determinada por su distancia desde el centro del círculo; cuanto más cerca del centro, mayor es la cuerda.

La definición de círculo y esencialmente todos los teoremas de esta y las dos siguientes secciones se pueden encontrar en el Libro III de los Elementos de Euclides.

Problemas

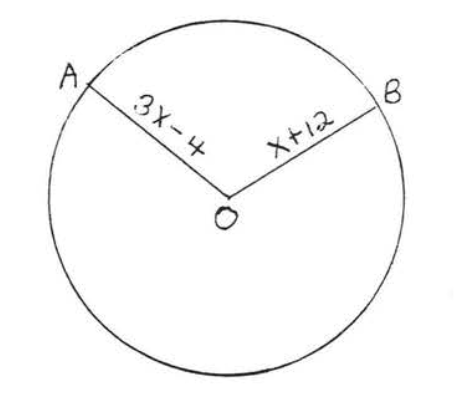

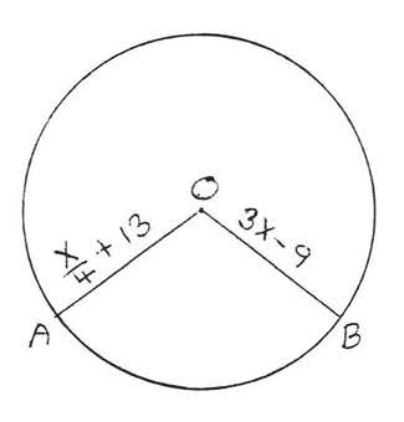

1 - 2. Encuentra el radio y el diámetro:

1.

2.

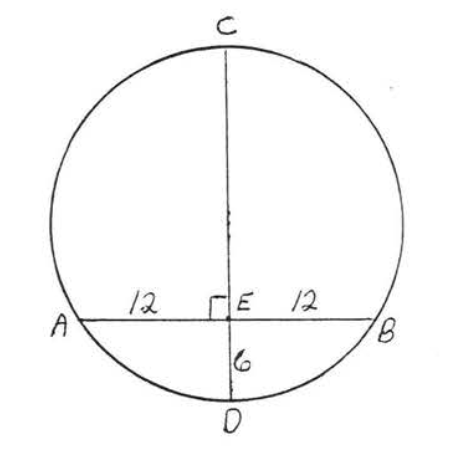

3 - 4. Encuentra\(AB\):

3.

4.

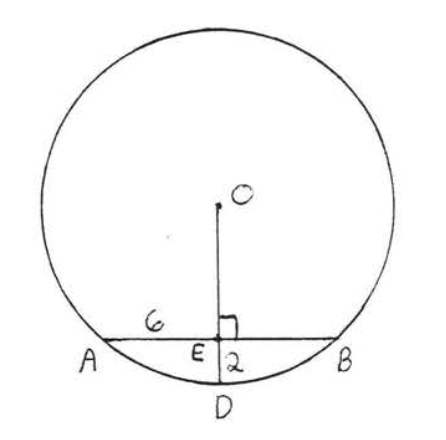

5 - 6. Encuentra\(x\):

5.

6.

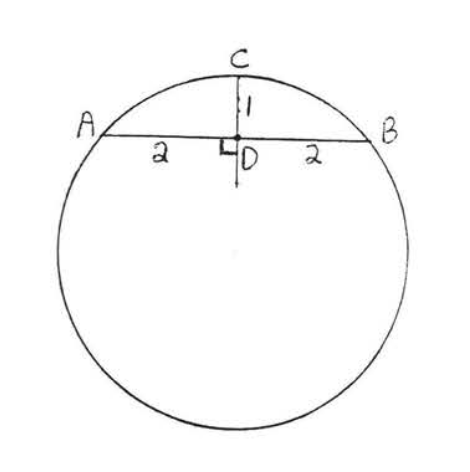

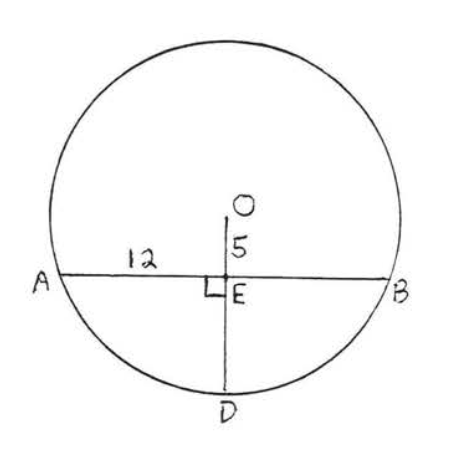

7 - 10. Encuentra el radio y el diámetro:

7.

8.

9.

10.

11 - 12. Encuentra las longitudes de\(AB\) y\(CD\):

11.

12.