7.3: Tangentes al Círculo

- Page ID

- 114776

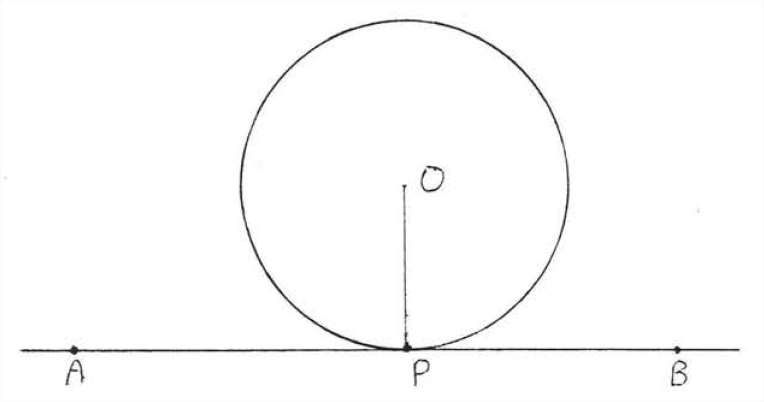

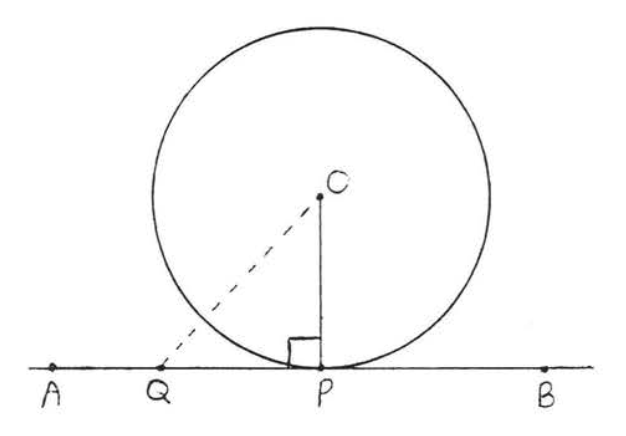

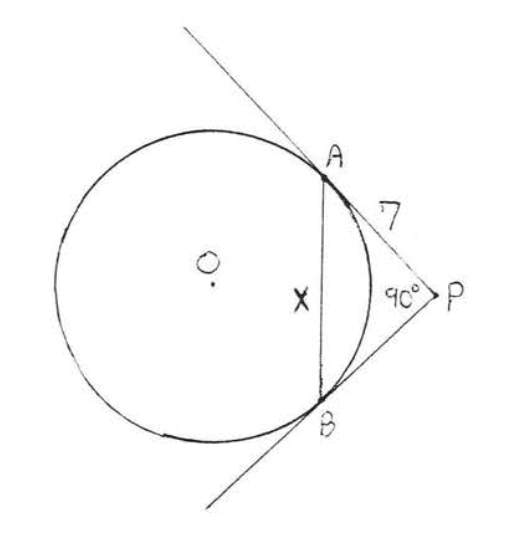

Una tangente a un círculo es una línea que cruza el círculo exactamente en un punto. En la Figura 1 la línea\(\overleftrightarrow{AB}\) es un círculo tangente que se cruza\(O\) justo en el punto\(P\).

Una tangente tiene la siguiente propiedad importante:

Una tangente es perpendicular al radio dibujado al punto de intersección.

- Prueba

-

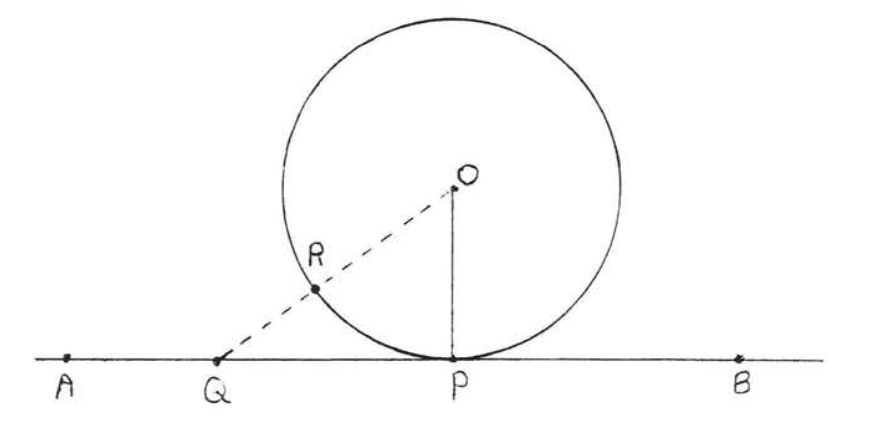

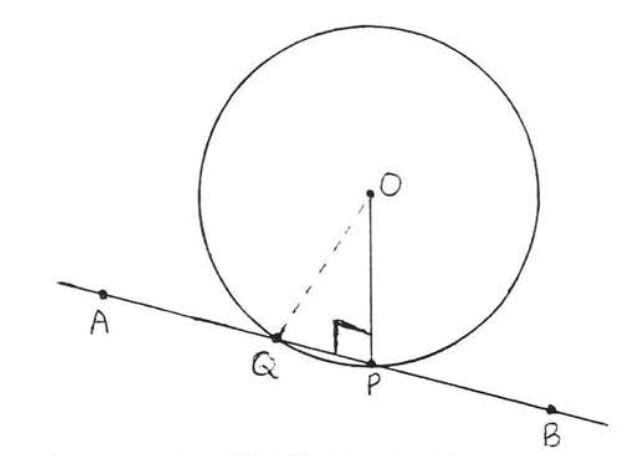

\(OP\)es el segmento de línea más corto que se puede dibujar de 0 a línea\(\overleftrightarrow{AB}\). Esto se debe a que si\(Q\) fuera otro punto en\(\overleftrightarrow{AB}\) entonces\(OQ\) sería más largo que el radio\(OR = OP\) (Figura\(\PageIndex{2}\)). Por lo tanto\(OP \perp \overleftrightarrow{AB}\) dado que el segmento de línea más corto que se puede dibujar de un punto a una línea recta es la perpendicular (Teorema\(\PageIndex{2}\), sección 4.6). Esto completa la prueba.

Figura\(\PageIndex{2}\):\(OP\) es el segmento de línea más corto que se puede dibujar de\(O\) a línea\(\overleftrightarrow{AB}\).

En la Figura la\(\PageIndex{1}\) tangente\(\overleftrightarrow{AB}\) es perpendicular al radio\(OP\) en el punto de intersección\(P\).

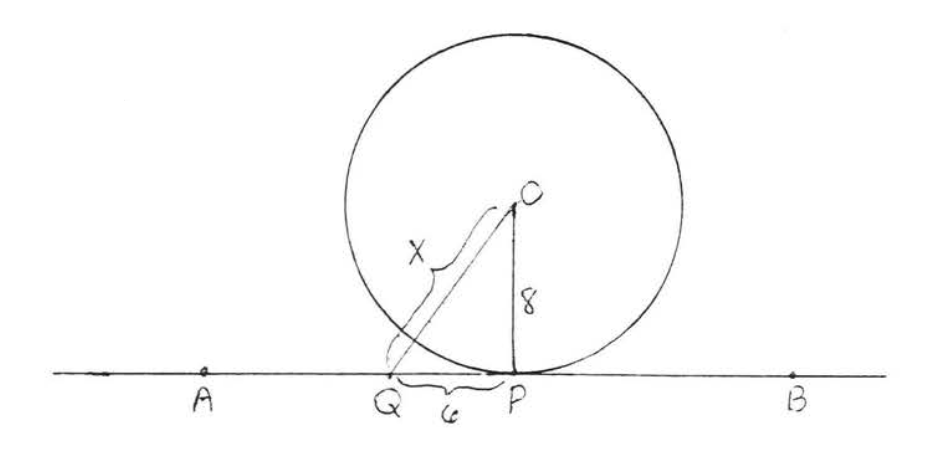

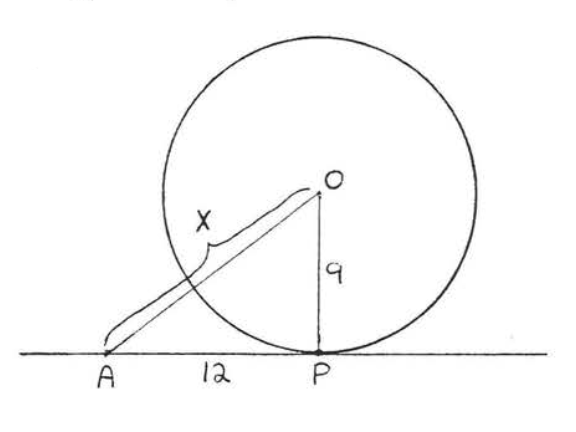

Encuentra\(x\):

Solución

Según el Teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\),\(\angle QPO\) es un ángulo recto. Por lo tanto, podemos aplicar el teorema de Pitágoras al triángulo rectángulo\(QPO\):

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {6^2 + 8^2} & = & {x^2} \\ {36 + 64} & = & {x^2} \\ {100} & = & {x^2} \\ {10} & = & {x} \end{array}\]

Respuesta:\(x = 10\).

Lo contrario del teorema también\(\PageIndex{1}\) es cierto:

Una línea perpendicular a un radio en un punto que toca el círculo debe ser una tangente.

En Figura\(\PageIndex{3}\), si\(OP \perp \overleftrightarrow{AB}\) entonces\(\overleftrightarrow{AB}\) debe ser una tangente; es decir,\(P\) es el único punto en el que\(\overleftrightarrow{AB}\) puede tocar el círculo (Figura\(\PageIndex{4}\)).

- Prueba

-

Supongamos que\(Q\) hubo algún otro punto sobre\(\overleftrightarrow{AB}\). Después\(OQ\) está la hipotenusa del triángulo rectángulo\(OPQ\) (ver Figura\(\PageIndex{3}\)). Según el Teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\), sección 4.6, la hipotenusa de un triángulo rectángulo siempre es mayor que una pierna. Por tanto, la hipotenusa\(OQ\) es mayor que la pierna\(OP\). Dado que\(OQ\) es mayor que el radio\(OP\),\(Q\) no puede estar en el círculo. Hemos demostrado que ningún otro punto sobre\(AB\) además\(P\) puede estar en el círculo. Por lo tanto\(\overleftrightarrow{AB}\) es una tangente. Esto completa la prueba.

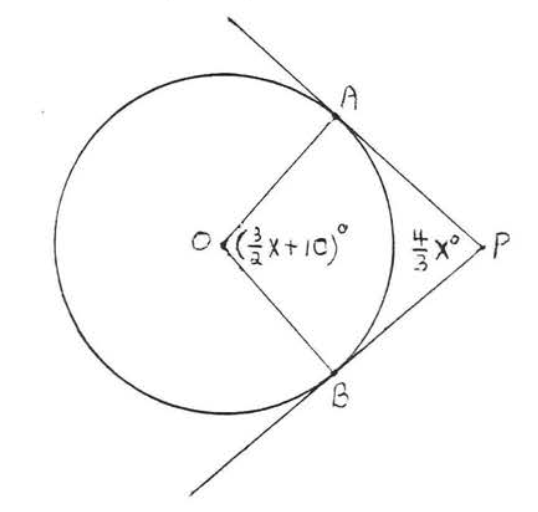

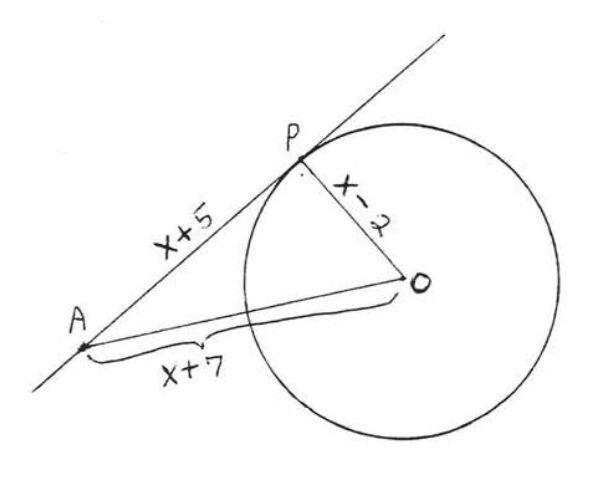

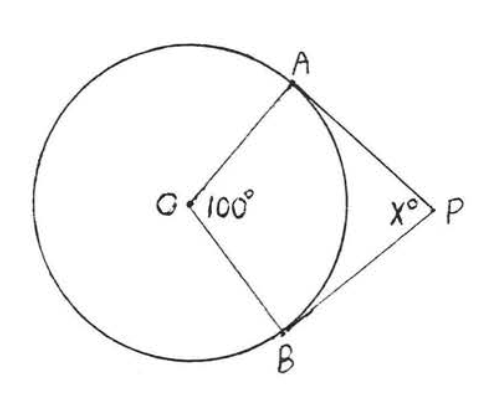

Buscar\(x\),\(\angle O\), y\(\angle P\):

Solución

\(\overleftrightarrow{AP}\)y\(\overleftrightarrow{BP}\) son tangentes a círculo\(O\), así por teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\),\(\angle OAP = \angle OBP = 90^{\circ}\). La suma de los ángulos del cuadrilátero\(AOBP\) es\(360^{\circ}\) (ver Ejemplo 1.5.5, sección 1.5), de ahí

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {90 + \left(\dfrac{3}{2} x + 10\right) + 90 + \dfrac{4}{3} x} & = & {360} \\ {\dfrac{3}{2}x + \dfrac{4}{3} x + 190} & = & {360} \\ {\dfrac{3}{2} x + \dfrac{4}{3} x} & = & {170} \\ {(6)\left(\dfrac{3}{2}x\right) + (6)\left(\dfrac{4}{3} x\right)} & = & {(6)(170)} \\ {9x + 8x} & = & {1020} \\ {17x} & = & {1020} \\ {x} & = & {60} \end{array}\]

Sustituyendo 60 por\(x\), encontramos

\(\angle O = \left(\dfrac{3}{2}x + 10\right)^{\circ} = \left(\dfrac{3}{2}(60) + 10\right)^{\circ} = (90 + 10)^{\circ} = 100^{\circ}\)

y

\(\angle P = \dfrac{4}{3} x^{\circ} = \dfrac{4}{3} (60)^{\circ} = 80^{\circ}\).

Comprobar:

\(\angle A + \angle O + \angle B + \angle P = 90^{\circ} + 100^{\circ} + 90^{\circ} + 80^{\circ} = 360^{\circ}.\)

Contestar

\(x = 60, \angle O = 100^{\circ}, \angle P = 80^{\circ}\).

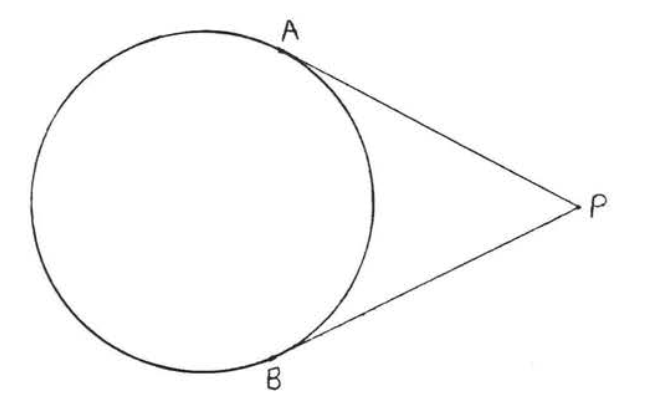

Si medimos segmentos de línea\(AP\) y\(BP\) en Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{2}\) encontraremos que son aproximadamente iguales en longitud. De hecho podemos demostrar que deben ser exactamente iguales:

Las tangentes dibujadas a un círculo desde un punto exterior son iguales.

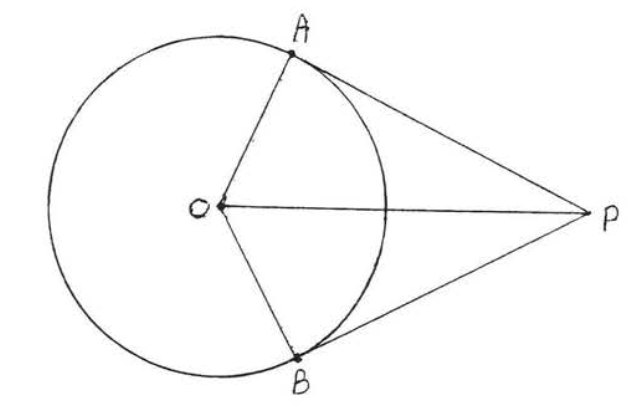

En Figura\(\PageIndex{5}\) si\(\overleftrightarrow{AP}\) y\(\overleftrightarrow{BP}\) son tangentes entonces\(AP = BP\).

- Prueba

-

Figura\(\PageIndex{6}\): Dibujar\(OA, OB\) y\(OP\). Dibujar\(OA, OB\), y\(OP\) (Figura\(\PageIndex{6}\)). \(OA = OB\)(todos los radios son iguales),\(OP = OP\) (identidad) y\(\angle A = \angle B = 90^{\circ}\) (Teorema (\ PageIndex {1}\)), de ahí\(\triangle AOP \cong \triangle BOP\) por Hyp-Leg = Hyp-Leg. Por\(AP = BP\) lo tanto, porque son lados correspondientes de triángulos congruentes.

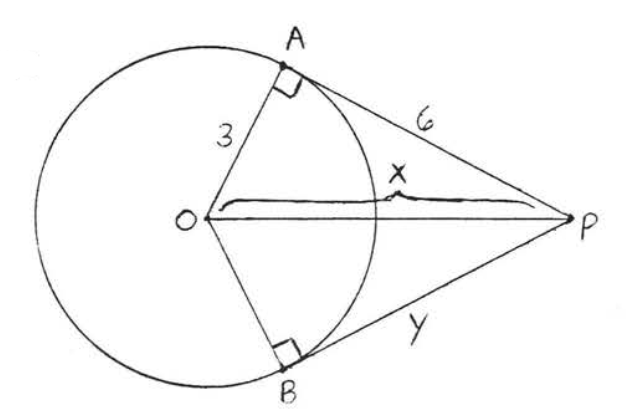

Encuentra\(x\) y\(y\):

Solución

Por el teorema de Pitágoras,\(x^2 = 3^2 + 6^2 = 9 + 36 = 45\) y\(x = \sqrt{45} = \sqrt{9}\sqrt{5} = 3\sqrt{5}\). Por teorema\(\PageIndex{3}\),\(y = BP = AP = 6\).

Respuesta:\(x = 3\sqrt{5}, y = 6\).

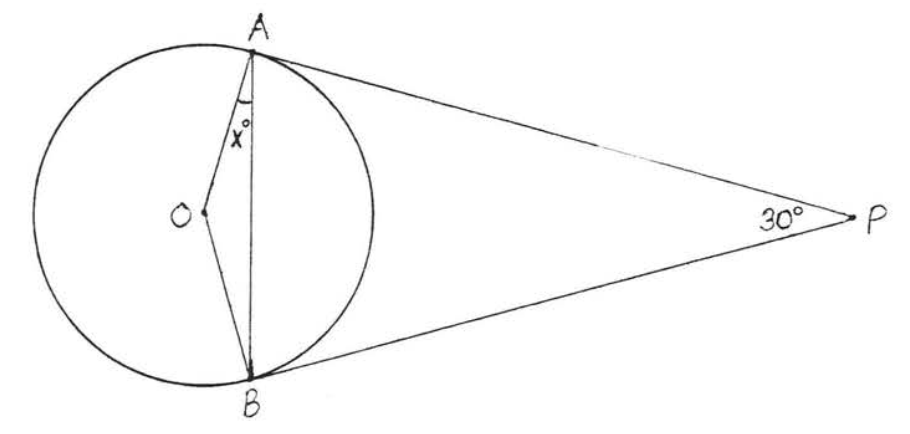

Encuentra\(x\):

Solución

Por teorema\(\PageIndex{3}\),\(AP = BP\). Así\(\triangle ABP\) es isósceles con\(\angle PAB = \angle PBA = 75^{\circ}\). Por lo tanto\(x^{\circ} = 90^{\circ} - 75^{\circ} = 15^{\circ}\).

Respuesta:\(x = 15\).

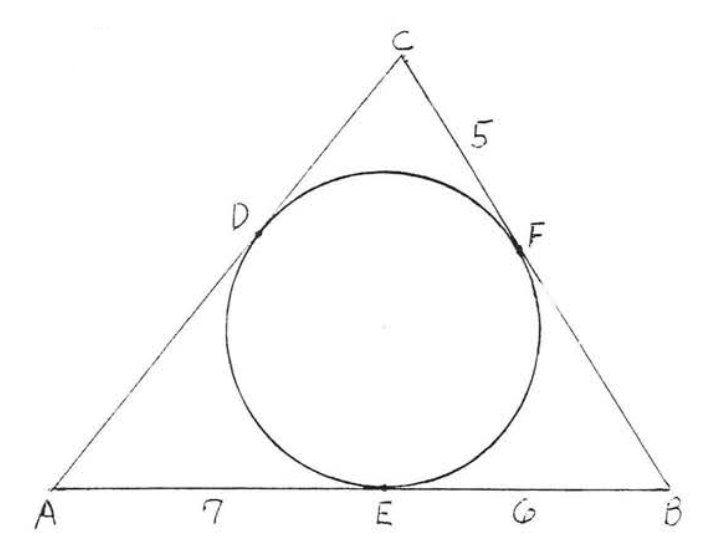

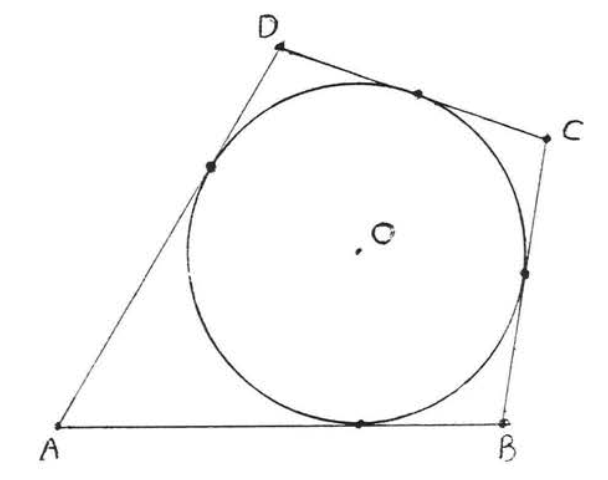

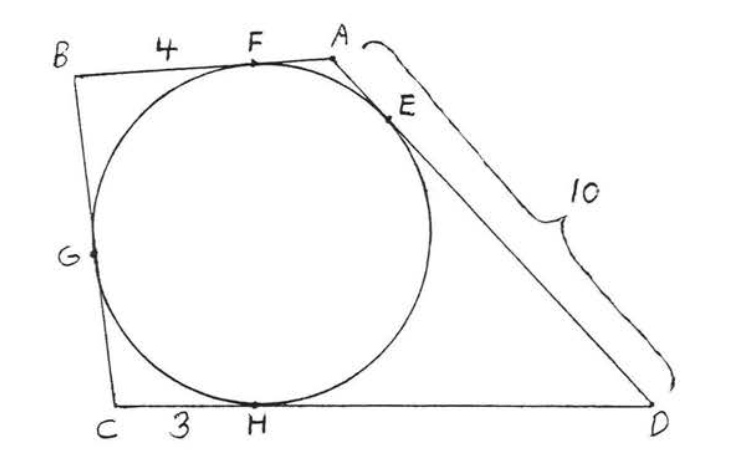

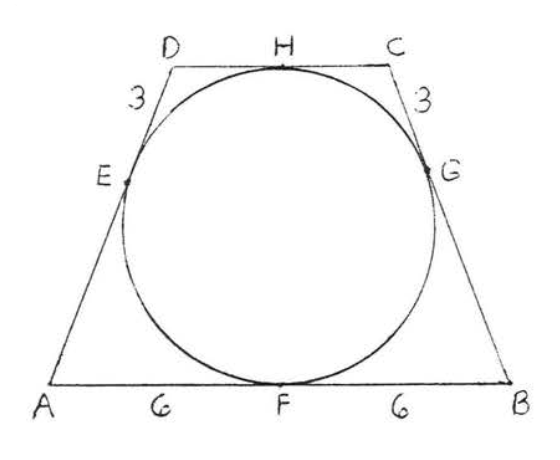

Si cada lado de un polígono es tangente a un círculo, se dice que el círculo está inscrito en el polígono y se dice que el polígono está circunscrito alrededor del círculo. En la Figura el\(\PageIndex{7}\) círculo 0 está inscrito en cuadrilátero\(ABCD\) y\(ABCD\) se circunscribe alrededor del círculo\(O\).

Encuentra el perímetro de\(ABCD\):

Solución

Por teorema\(\PageIndex{3}\),\(CG = CH = 3\) y\(BG = BF = 4\). También\(DH = DE\) y\(AF = AE\) así\(DH + AF = DE + AE =10\).

Por lo tanto, el perímetro de\(ABCD = 3 + 3 + 4 + 4 + 10 + 10 = 34.\)

Respuesta:\(P = 34\).

Problemas

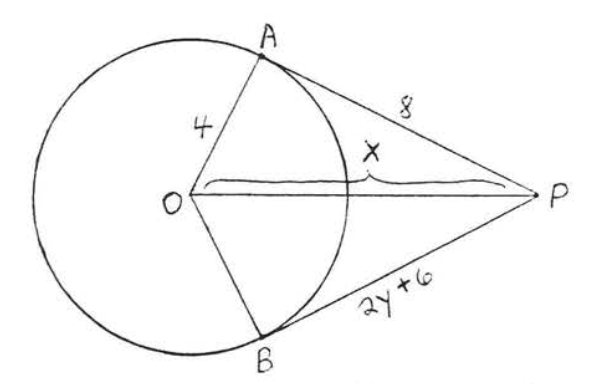

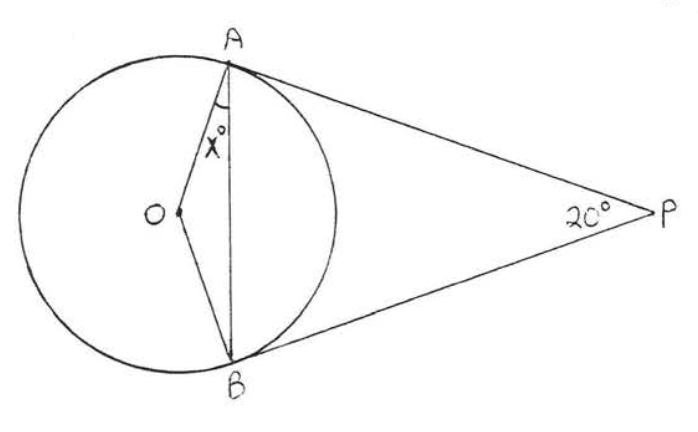

1 - 4. Encuentra\(x\):

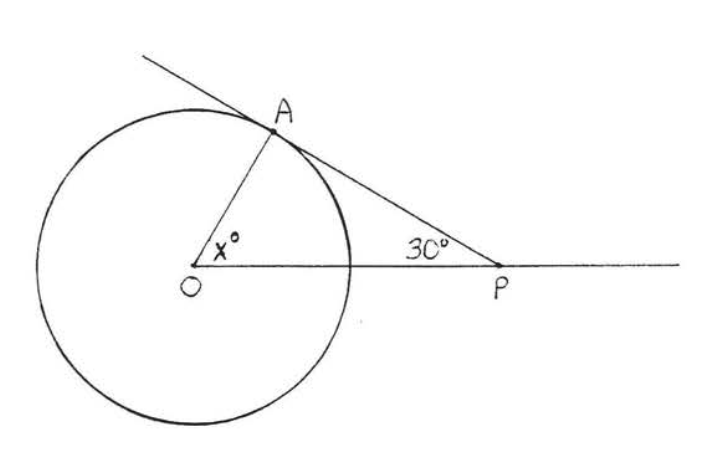

1.

2.

3.

4.

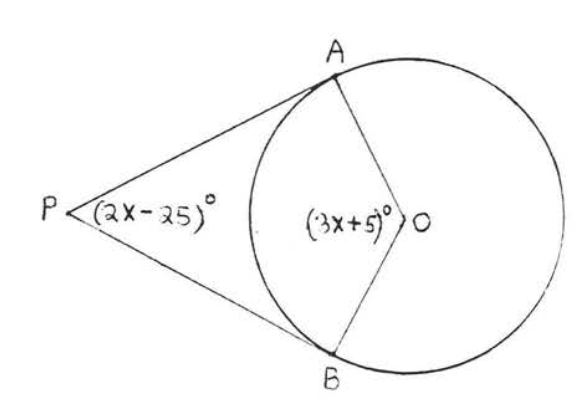

5 - 6. Buscar\(x\),\(\angle O\) y\(\angle P\):

5.

6.

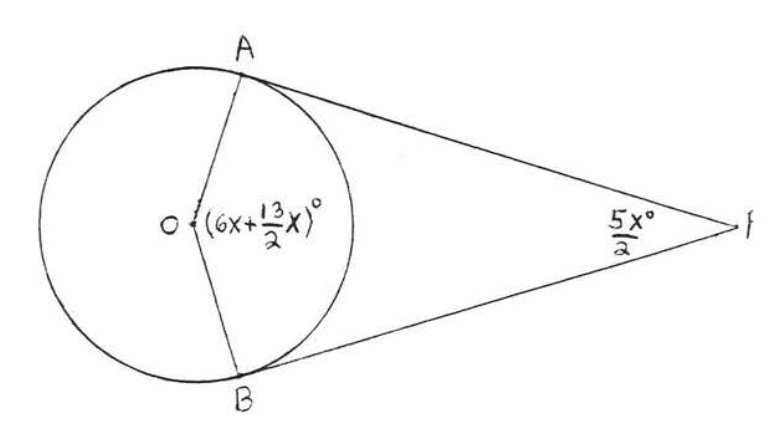

7 - 8. Encuentra\(x\) y\(y\):

7.

8.

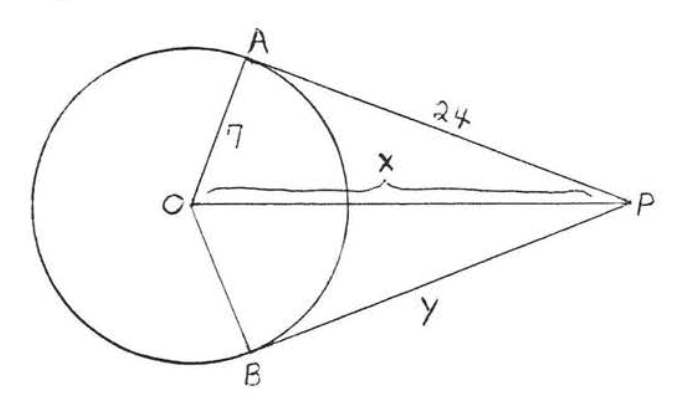

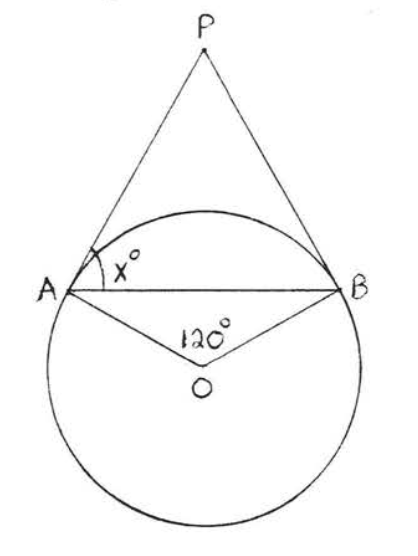

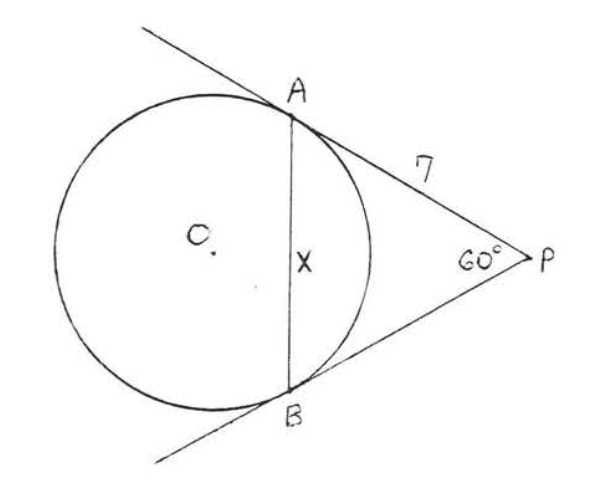

9 - 12. Encuentra\(x\):

9.

10.

11.

12.

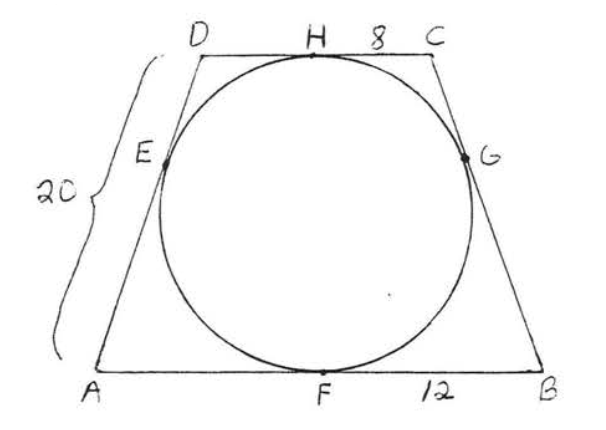

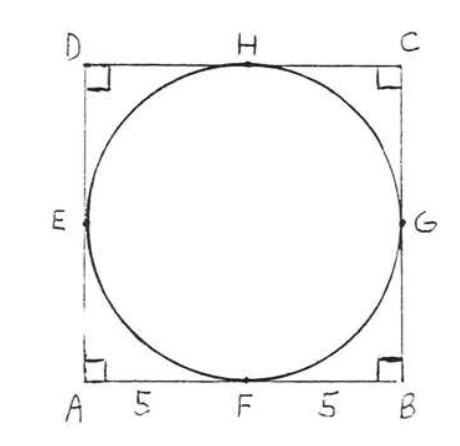

13 - 16. Encuentra el perímetro del polígono:

13.

14.

15.

16.