7.4: Grados en un Arco

- Page ID

- 114748

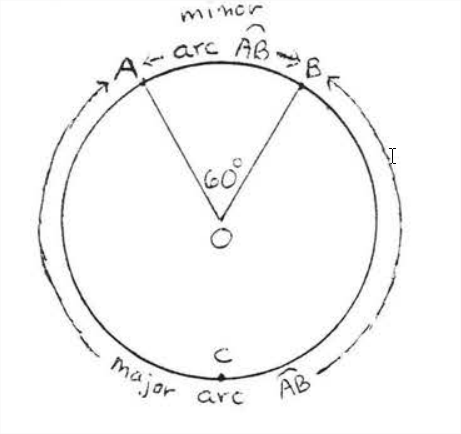

Un arco es una parte del círculo incluido entre dos puntos. El símbolo para el se incluyen entre puntos\(A\) e\(B\) Is\(\widehat{AB}\). En la Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\) hay dos arcos determinados por\(A\) y\(B\). El más corto se llama arco menor y el más largo se llama arco mayor. A menos que se indique lo contrario, siempre se\(\widehat{AB}\) referirá al arco menor. En\(\PageIndex{1}\), también podríamos escribir\(\widehat{ACB}\) en lugar de\(\widehat{AB}\) interceptar el arco mayor.

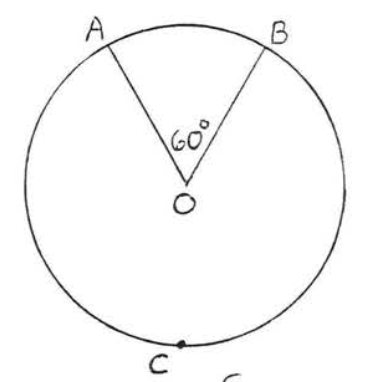

Un ángulo central es un vértice de ángulo es el centro del círculo y cuyos lados son radios. En la Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\),\(\angle AOB\) se encuentra un ángulo central. \(\angle AOB\)se dice que intercepta arco\(\widehat{AB}\).

El número de grados en un arco se define como el número de grados en el ángulo central que intercepta el arco. En la Figura 1 menor se\(\widehat{AB}\) tiene\(60^{\circ}\) porque\(\angle AO 3=60^{\circ}\), escribimos\(\widehat{AB} \stackrel{\circ}{=} 60^{\circ},\) donde el símbolo\(\stackrel{\circ}{=}\) significa igual en grados. El\(=\) símbolo plano se reservará para la longitud del arco, a ser discutido en la Sección 7.5.

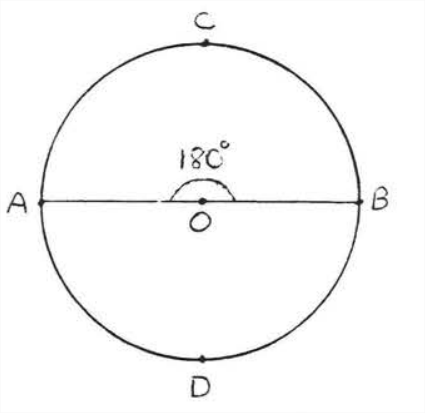

En la Figura 2\(\angle AOB\) se encuentra un ángulo recto así\(\angle AOB=180^{\circ}\) y\(\widehat{ACB} \stackrel{\circ}{=} 180^{\circ} .\) Similarmente\(\widehat{ADB} \stackrel{\circ}{=} 180^{\circ}\). Cada uno de estos arcos se llama semicírculo. El círculo completo mide\(360^{\circ} \).

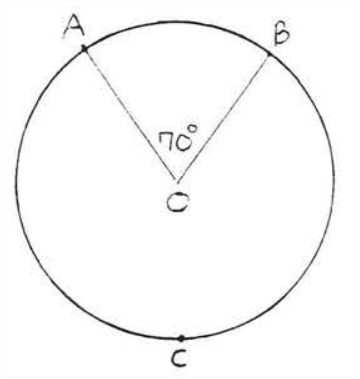

Encuentra el número de grados en arcos\(\widehat{AB}\) y\(\widehat{ACB}\):

Solución

\(\widehat{A B} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \angle A C B=\angle A C B=70^{\circ}\)y\( \widehat{A C B} \stackrel{\circ}{=} 360^{\circ}-\widehat{A B} \stackrel{\circ}{=} 360^{\circ}-70^{\circ}=290^{\circ} .\)

Respuesta:\(\widehat{A B} \stackrel{\circ}{=} 70^{\circ}, \widehat{A C B} \stackrel{\circ}{=} 290^{\circ}\)

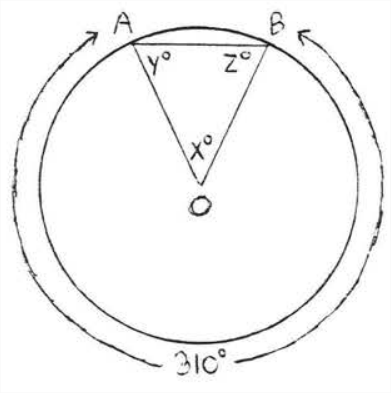

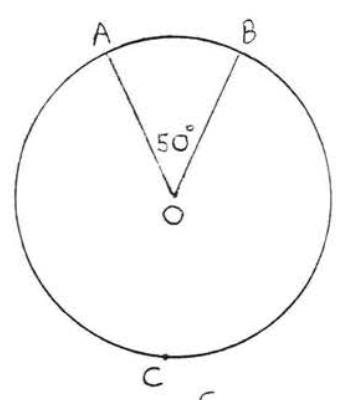

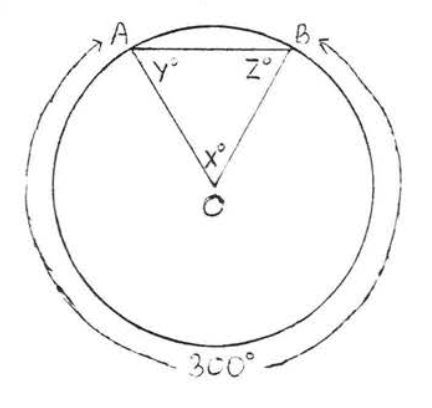

Encuentra\(x, y\) y\(z\):

Solución

\(x^{\circ} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \widehat{A B} \stackrel{\circ}{=} 360^{\circ}-310^{\circ}=50^{\circ}, O A=O B\)ya que todos los radios son iguales. Por lo tanto\(\triangle AOB\) es isósceles con\(y^{\circ}=z^{\circ} .\) Tenemos

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {x^{\circ} + y^{\circ} + z^{\circ}} & = & {180^{\circ}} \\ {50^{\circ} + y^{\circ} + y^{\circ}} & = & {180^{\circ}} \\ {2y^{\circ}} & = & {130^{\circ}} \\ {y^{\circ}} & = & {65^{\circ}} \end{array}\]

Respuesta:\(x = 50, y = z = 65\).

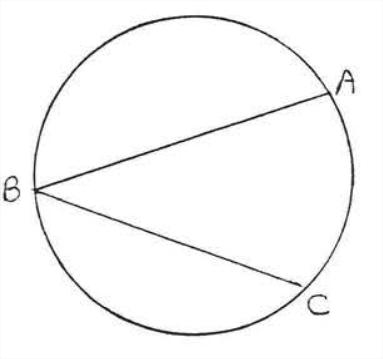

Un ángulo inscrito es un ángulo cuyo vértice está sobre un círculo y cuyas estáes son acordes del círculo. En la Figura\(\PageIndex{3}\),\(\angle ABC\) se encuentra un ángulo inscrito. \(\angle ABC\)se dice que interceptar son\(\widehat{AC}\)

FIGURA\(\PageIndex{3}\):\(\angle ABC\) es un ángulo inscrito.

Demostraremos el siguiente teorema:

Un ángulo inscrito\(\stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2}\) de su arco interceptado.

En la Figura\(\PageIndex{3}, \angle A B C \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{A C}\)

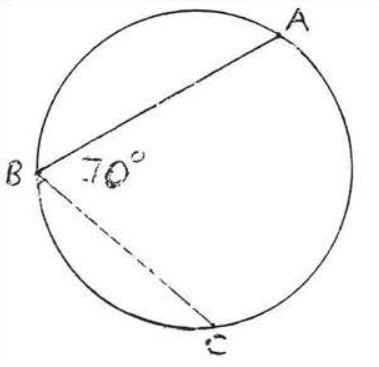

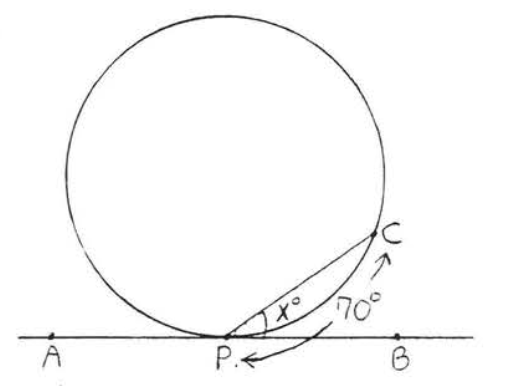

Encuentra el número de grados en\(\widehat{AC}\):

Solución:\(\angle ABC=70^{\circ} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{AC} .\) Por lo tanto\(\widehat{AC} \stackrel{\circ}{=} 140^{\circ}\)

Respuesta:\(\widehat{A C} \stackrel{\circ}{=} 140^{\circ}\)

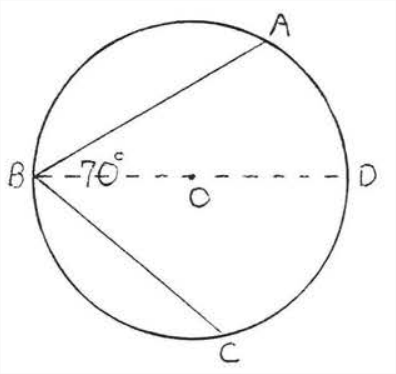

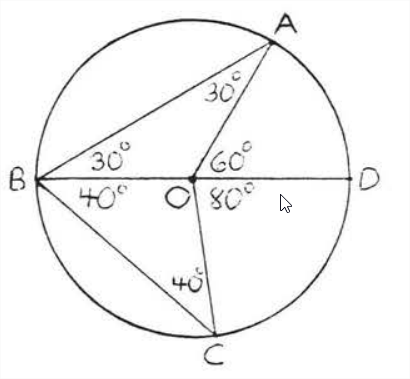

Antes de dar la prueba del Teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\) veamos si podemos probar la respuesta al EJEMPLO\(\PageIndex{3}\). Dibuja el diámetro desde\(B\) el centro\(O\) (Figura\(\PageIndex{4}\)). \(\angle A B C\)se divide por el diámetro en dos ángulos más pequeños,\(\angle A B D\) y\(\angle D B C\), cuya suma es\(70^{\circ}\). Supongamos\(\angle ABD = 30^{\circ}\) y\(\angle DBC = 40^{\circ}\) (Figura\(\PageIndex{5}\)). \(AO = BO\)porque todos los radios son iguales. De ahí\(\triangle AOB\) es isósceles con\(\angle A=\angle ABD=30^{\circ}\) Similarmente\(\angle C=\angle DBC=40^{\circ}\). \(\angle AOD\)es un ángulo exterior de\(\triangle AOB\) y por lo tanto es igual a la suma de los ángulos interiores remotos,\(30^{\circ} + 30^{\circ} = 60^{\circ}\) (Teorema 1.5.2 sección 1.5). De igual manera\(\angle COD = 40^{\circ} + 40^{\circ} = 80^{\circ}\). Por lo tanto ángulo central\(\angle AOC = 60^{\circ} + 80^{\circ} = 140^{\circ}\) y arco\(\widehat{AC} \stackrel{\circ}{=} 140^{\circ}\). Esto concuerda con nuestra respuesta al Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{3}\).

Ahora vamos a dar una prueba formal del Teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\), que sostendrá para cualquier ángulo inscrito:

Prueba de teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\): Hay tres casos según si el centro está en, dentro o fuera del ángulo inscrito (Figuras\(\PageIndex{6}\),\(\PageIndex{7}\) y\(\PageIndex{8}\)).

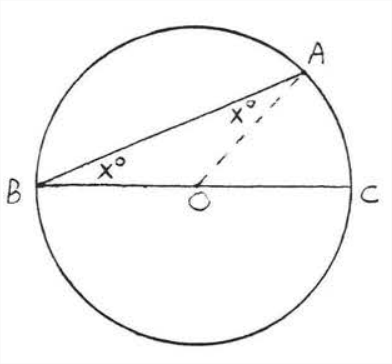

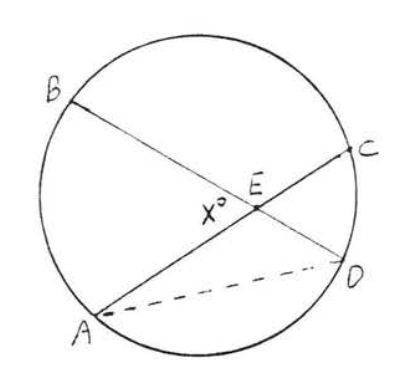

Caso I. El centro está en la Angie inscrita (Figura\(\PageIndex{6}\)). Empate\(AO\). Los radit son iguales así\(AO = BO\) y\(\angle A=\angle B=x^{\circ} .\) Por lo tanto\(\widehat{AC} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \angle AOC=x^{\circ}+x^{\circ}=2 x^{\circ}\) y\(\angle A B C=x^{\circ} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{AC}\).

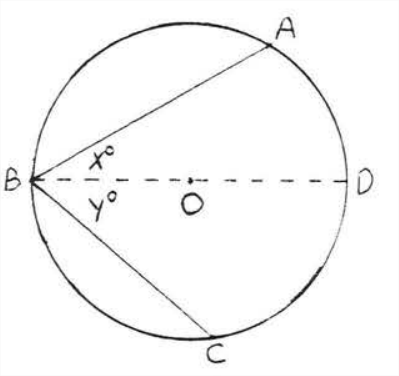

Caso II. El centro se encuentra dentro del ángulo inscrito (Figura\(\PageIndex{7}\)). Dibuje el diámetro\(BD\) de\(B\) a través\(O\). Por caso yo conocemos\(\angle A B D=x^{\circ} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{AD}\) y\(\angle DBC=y^{\circ} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{DC} .\) por lo tanto\[\angle ABC=x^{\circ}+y^{\circ} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{AD}+\dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{DC} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2}(\widehat{AD}+\widehat{DC}) \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{AC}\]

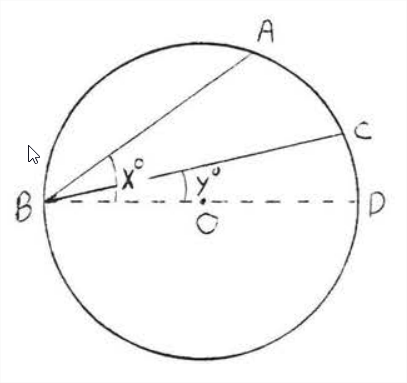

Caso III. El centro está fuera del ángulo inscrito (Figura\(\PageIndex{8}\)). Dibuje el diámetro\(BD\) de\(B\) a través\(O\). Por caso yo sabemos\(\angle A B D=x^{\circ} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{AD}\) y\(\angle CBD=y^{\circ} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{CD}\). Por lo tanto\[ \angle ABC=x^{\circ}-y^{\circ} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \hat{AD}-\dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{CD} \stackrel{\circ}{=}\dfrac{1}{2}(\widehat{AD}-\widehat{CD}) \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{AC}\]

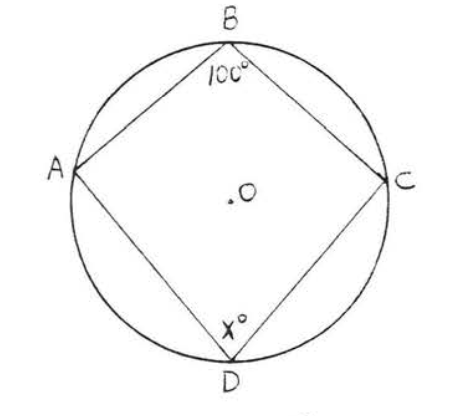

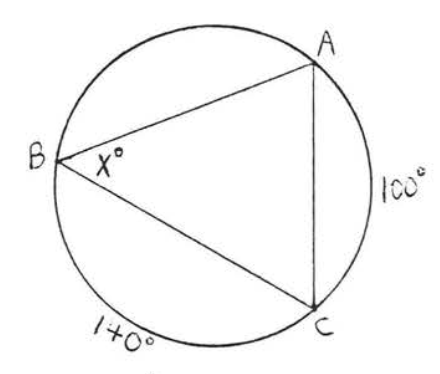

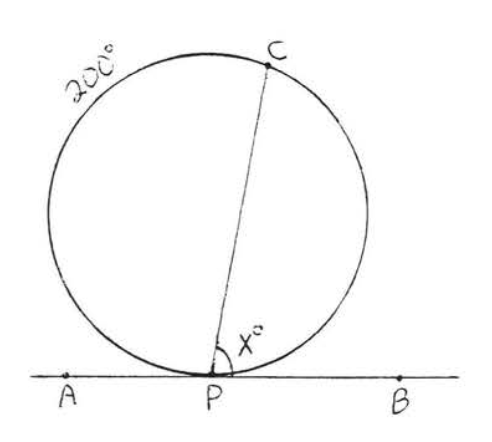

Encuentra\(x\):

Solución

\(\angle B = 100^{\circ} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{ADC}\). Por lo tanto\(\widehat{ADC} = 200^{\circ}\). Entonces\(\widehat{ABC} \stackrel{\circ}{=} 360^{\circ} - 200^{\circ} = 160^{\circ}\) y\(x^{\circ} = \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{ABC} = \dfrac{1}{2} (160^{\circ}) = 80^{\circ}\).

Respuesta:\(x = 80\).

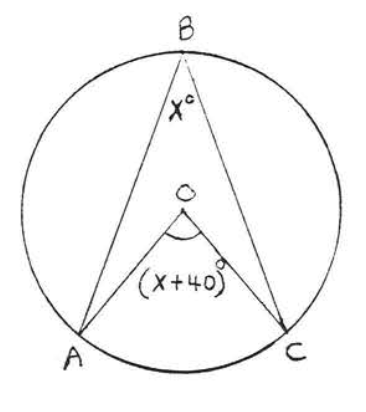

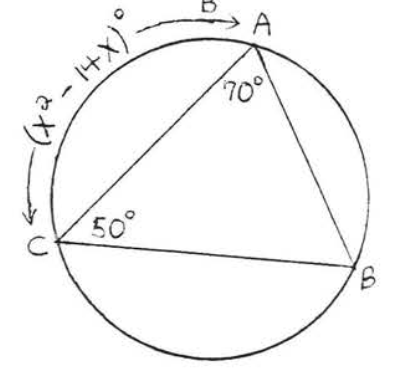

Encuentra\(x\):

Solución

\(\angle B = x^{\circ} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{AC}\). También\(\widehat{AC} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \angle AOC = (x + 40)^{\circ}\). Tenemos

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {\angle B} & \stackrel{\circ}{=} & {\dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{AC}} \\ {x} & = & {\dfrac{1}{2} (x + 40)} \\ {2x} & = & {x + 40} \\ {x} & = & {40} \end{array}\]

Comprobar:

\(\angle B \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{AC}\)

\[\begin{array} {r|l} {x^{\circ}} & {\dfrac{1}{2} (x + 40)^{\circ}} \\ {40^{\circ}} & {\dfrac{1}{2} (40^{\circ} + 40^{\circ})^{\circ}} \\ {} & {\dfrac{1}{2} (80)^{\circ}} \\ {} & {40^{\circ}} \end{array}\]

Respuesta:\(x = 40\).

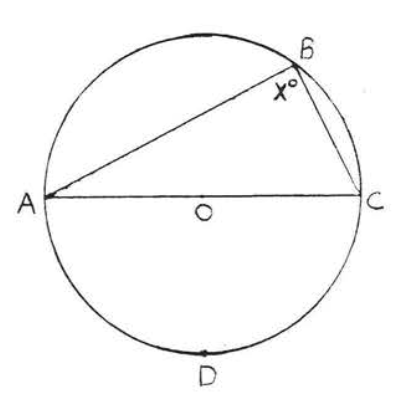

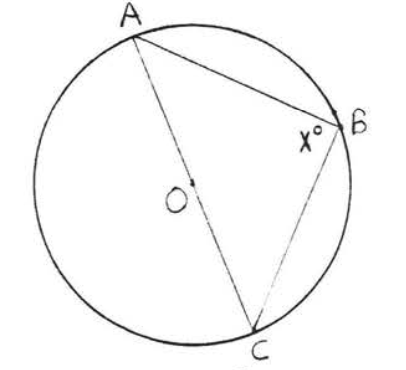

Encuentra\(x\):

Solución

\(\widehat{ADC}\)es un semicírculo así\(\widehat{ADC} \stackrel{\circ}{=} 180^{\circ}\). \(\angle B = x^{\circ} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{ADC} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} (180^{\circ}) = 90^{\circ}\).

Respuesta:\(x = 90\).

Anotamos el resultado de Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{6}\) como teorema:

Un ángulo inscrito en un semicírculo es un ángulo recto.

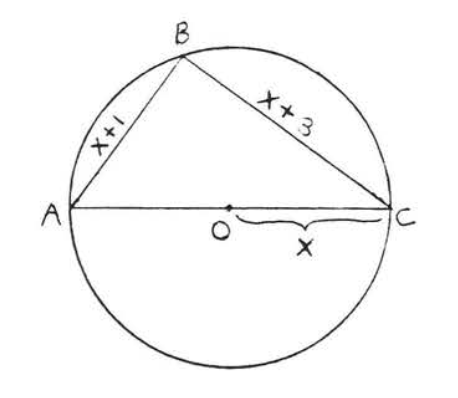

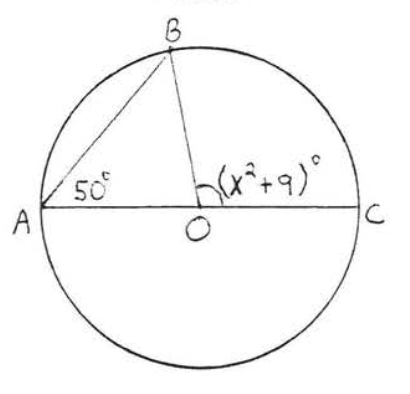

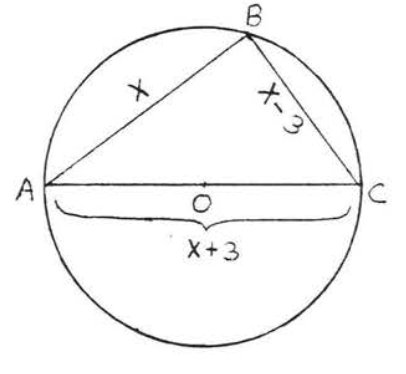

Encuentra\(x\):

Solución

Según el Teorema\(\PageIndex{2}\)\(\angle B = 90^{\circ}\). Por lo tanto\(\triangle ABC\) es un triángulo rectángulo y podemos aplicar el teorema de Pitágoras:

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {\text{AB}^2 + \text{BC}^2} & = & {\text{AC}^2} \\ {(x + 1)^2 + (x + 3)^2} & = & {(2x)^2} \\ {x^2 + 2x + 1 + x^2 + 6x + 9} & = & {4x^2} \\ {2x^2 + 8x + 10} & = & {4x^2} \\ {0} & = & {2x^2 - 8x - 10} \\ {0} & = & {x^2 - 4x - 5} \\ {0} & = & {(x - 5)(x + 1)} \end{array}\]

\(\begin{array} {rcl} {0} & = & {x - 5} \\ {x} & = & {5} \end{array}\)\(\begin{array} {rcl} {0} & = & {x + 1} \\ {x} & = & {-1} \end{array}\)

Rechazamos la respuesta\(x = -1\) ya que\(OC = x\) debe tener longitud positiva.

Comprobar,\(x = 5\):

\(\text{AB}^2 + \text{BC}^2 = \text{AC}^2\)

\[\begin{array} {r|l} {(x + 1)^2 + (x + 3)^2} & {(2x)^2} \\ {(5 + 1)^2 + (5 + 3)^2} & {(2(5))^2} \\ {6^2 + 8^2} & {10^2} \\ {36 + 64} & {100} \\ {100} & {} \end{array}\]

Respuesta:\(x = 5\).

Los siguientes cuatro teoremas son todas consecuencias del Teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\):

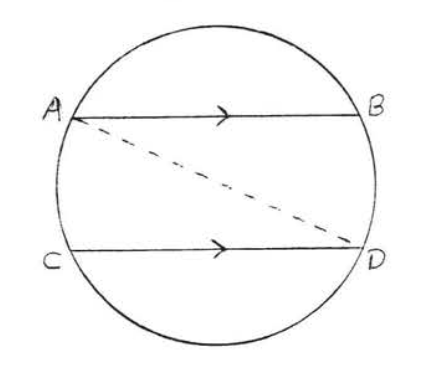

Las líneas paralelas interceptan arcos iguales en grados.

En Figura\(\PageIndex{9}\) si\(AB\) ||\(CD\) entonces\(\widehat{AC} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \widehat{BD}\).

Figura\(\PageIndex{9}\). Si\(AB\) ||\(CD\) entonces\(\widehat{AC}\)\ stackrel {\ circ} {=}\(\widehat{BD}\).

Figura\(\PageIndex{9}\). Si\(AB\) ||\(CD\) entonces\(\widehat{AC}\)\ stackrel {\ circ} {=}\(\widehat{BD}\).

- Prueba

-

Empate\(AD\). Entonces\(\angle ADC \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{AC}\) y\(\angle BAD \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{BD}\). También\(\angle ADC = \angle BAD\) porque son ángulos interiores alternos de líneas paralelas\(AB\) y\(CD\) .Por lo tanto\(\dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{AC} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{BD}\) y\(\widehat{AC} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \widehat{BD}\).

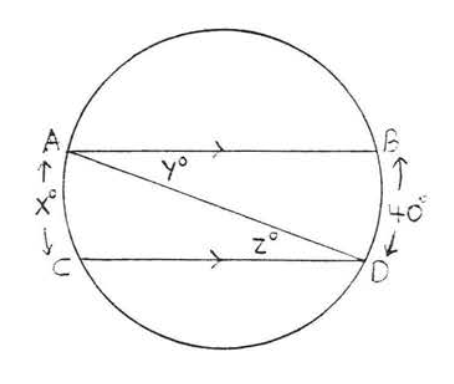

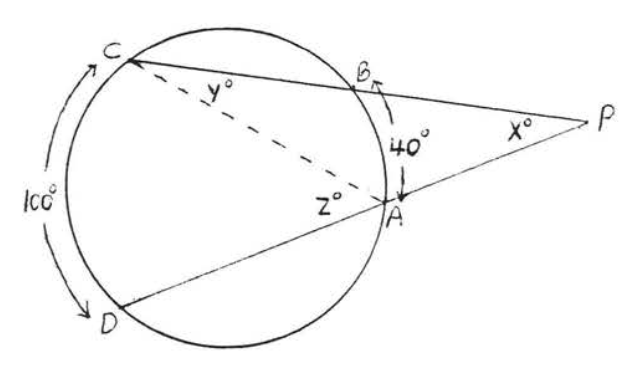

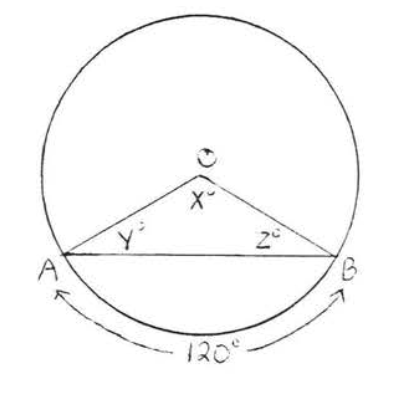

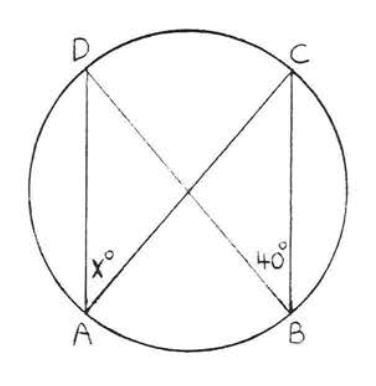

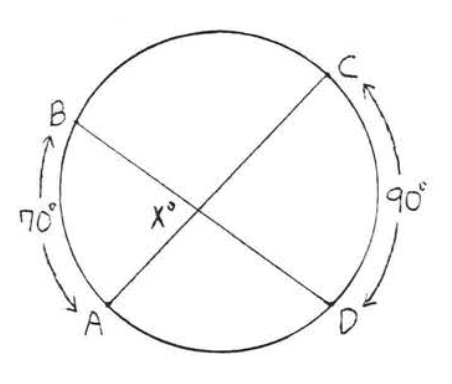

Encuentra\(x, y\) y\(z\):

Solución

Por teorema\(\PageIndex{3}\)\(x^{\circ} = 40^{\circ}\). \(y^{\circ} = z^{\circ} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{AC} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{BD} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} (40^{\circ}) = 20^{\circ}\).

Respuesta:\(x = 40, y = z = 20\).

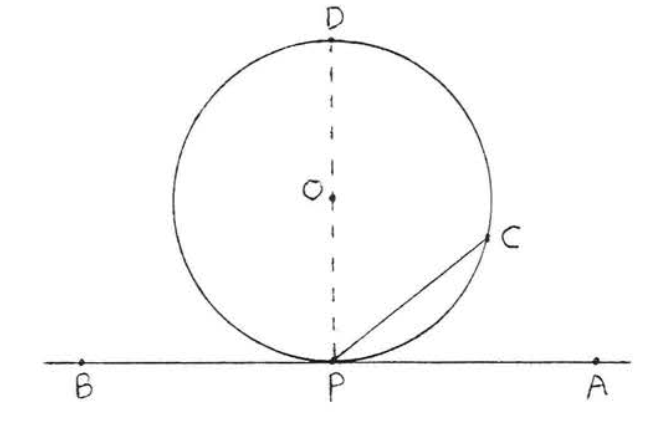

Un ángulo formado por una tangente y una cuerda es\(\stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2}\) de su arco interceptado.

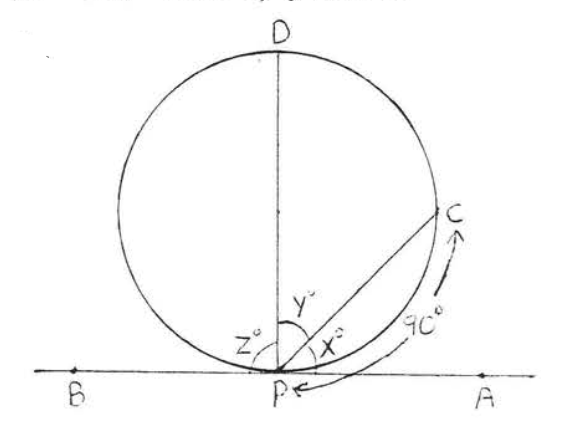

En la Figura\(\PageIndex{10}\)\(\angle APC \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{PDC}\).

Figura\(\PageIndex{10}\). \(\angle APC\)y\(\angle BPC\) están formados por tangente\(\overleftrightarrow{AB}\) y acorde\(PC\).

Figura\(\PageIndex{10}\). \(\angle APC\)y\(\angle BPC\) están formados por tangente\(\overleftrightarrow{AB}\) y acorde\(PC\).

- Prueba

-

En Figura\(\PageIndex{10}\) dibujar diámetro\(PD\). Entonces por el Teorema 7.3.1 de la sección 7.3\(\angle APD = \angle BPD = 90^{\circ}\). Por Teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\) de esta sección\(\angle CPD \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{CD}\). \(\angle APC = 90^{\circ} - \angle CPD \stackrel{\circ}{=} 90^{\circ} - \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{CD} \stackrel{\circ}{=} 90^{\circ} - \dfrac{1}{2} (180^{\circ} - \widehat{PC}) \stackrel{\circ}{=} 90^{\circ} - 90^{\circ} + \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{PC} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{PC}\). \(\angle BPC = 90^{\circ} + \angle CPD \stackrel{\circ}{=} 90^{\circ} + \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{CD} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} (180^{\circ} + \widehat{CD}) \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{PDC}\).

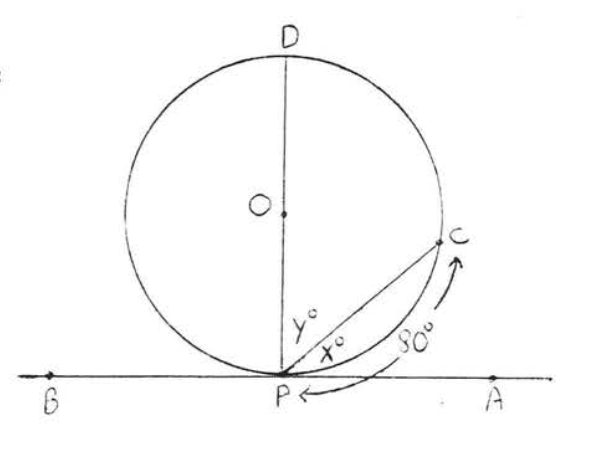

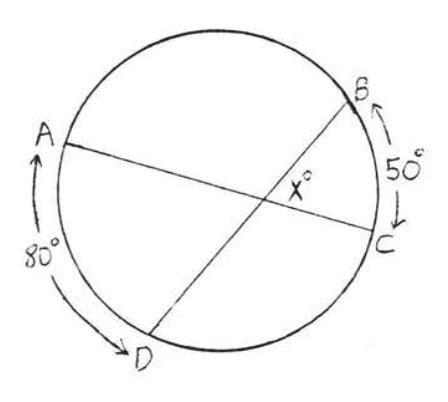

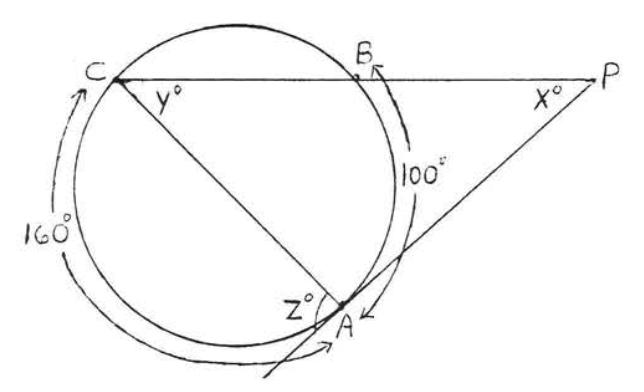

Encuentra\(x, y\) y\(\widehat{CD}\):

Solución

Por teorema\(\PageIndex{4}\)\(x^{\circ} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{PC} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} (80^{\circ}) = 40^{\circ}\). \(y^{\circ} = 90^{\circ} - x^{\circ} = 90^{\circ} - 40^{\circ} = 50^{\circ}\). \(\widehat{CD} \stackrel{\circ}{=} 180^{\circ} - \widehat{CP} \stackrel{\circ}{=} 180^{\circ} - 80^{\circ} = 100^{\circ}\).

Respuesta:\(x = 40\),\(y = 50\),\(\widehat{CD} \stackrel{\circ}{=} 100^{\circ}\).

Un ángulo formado por dos cuerdas que se cruzan es\(\stackrel{\circ}{=}\) a\(\dfrac{1}{2}\) la suma de los arcos interceptados.

En la Figura\(\PageIndex{11}\)\(x^{\circ} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} (\widehat{AB} + \widehat{CD})\).

- Prueba

-

\(\angle ADB \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{AB}\)y\(\angle CAD \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{CD}\). Por Teorema 1.5.2, sección 1.5, un ángulo exterior de un triángulo es igual a la suma de los dos ángulos interiores remotos. Por lo tanto\(x^{\circ} = \angle ADB + \angle CAD \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{AB} + \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{CD} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} (\widehat{AB} + \widehat{CD})\).

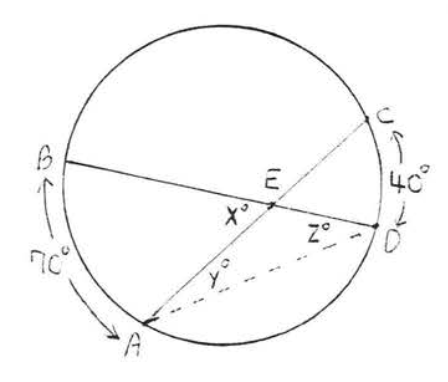

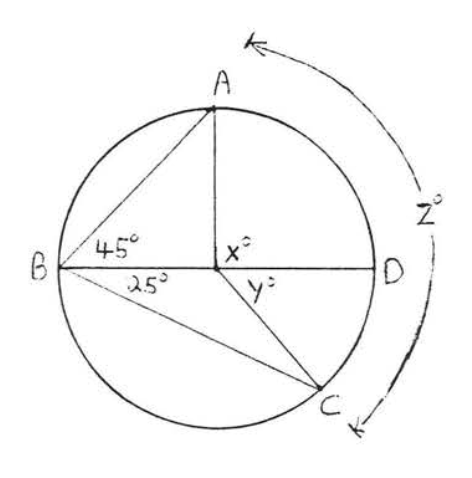

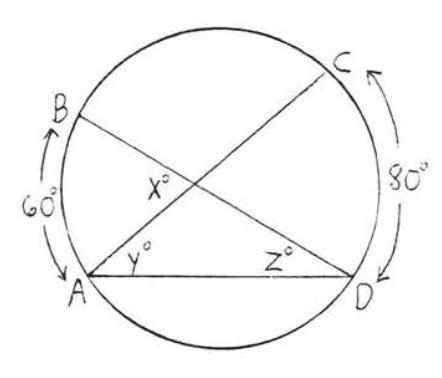

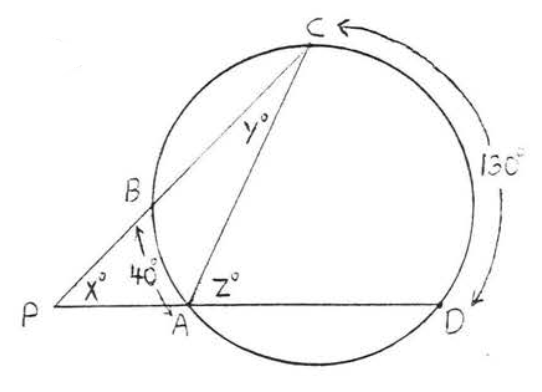

Encuentra\(x, y\) y\(z\):

Solución

Por teorema\(\PageIndex{5}\),\(x^{\circ} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} (\widehat{AB} + \widehat{CD}) \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} (70^{\circ} + 40^{\circ}) = \dfrac{1}{2}(110^{\circ}) = 55^{\circ}\). \(y^{\circ} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{CD} = \dfrac{1}{2} (40^{\circ}) = 20^{\circ}\),\(z^{\circ} = \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{AB} = \dfrac{1}{2}(70^{\circ}) = 35^{\circ}\).

Respuesta:\(x = 55, y = 20, z = 35\).

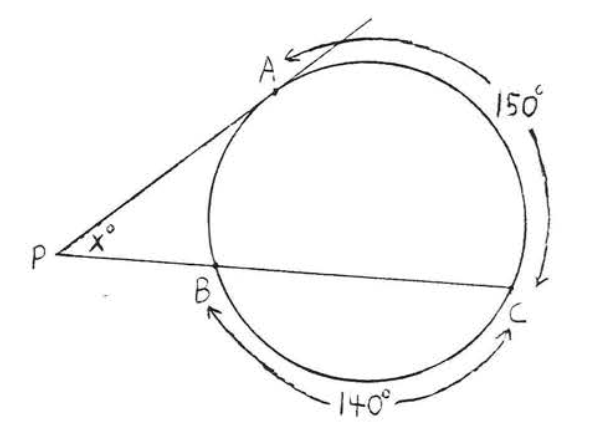

Una línea que cruza un círculo en dos puntos se llama secante. En la Figura\(\PageIndex{12}\),\(PC\) es una secante.

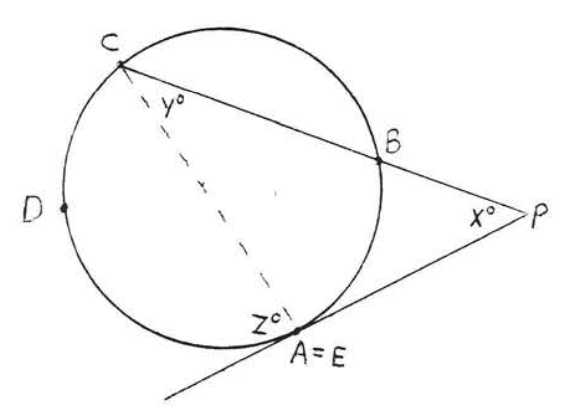

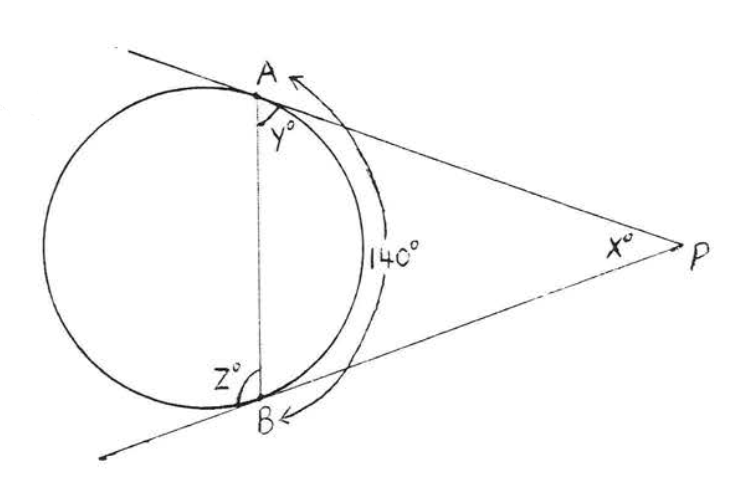

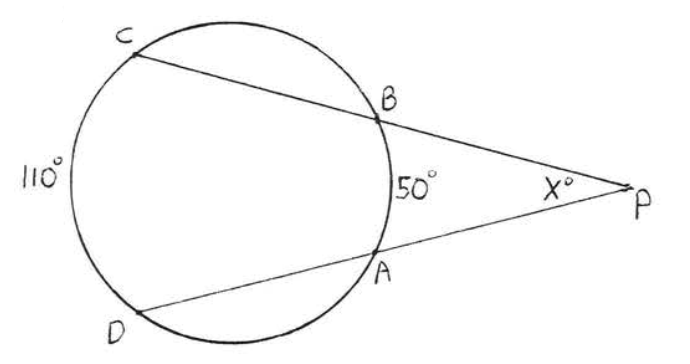

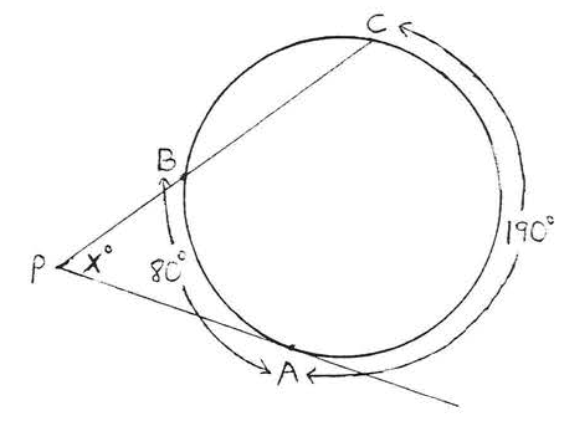

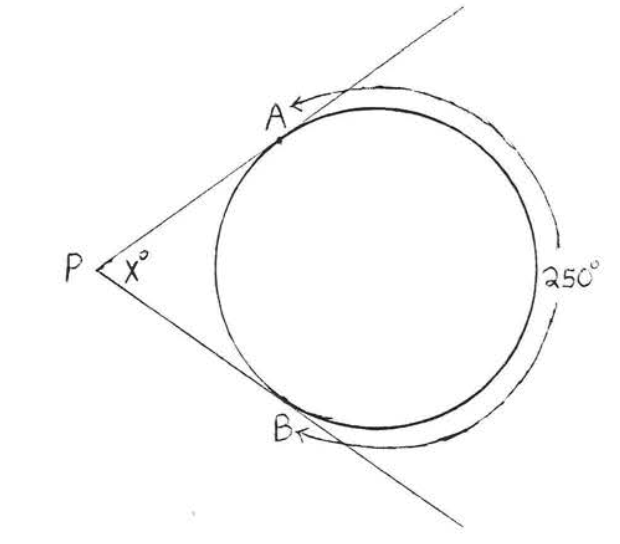

Un ángulo formado fuera de un círculo por dos secantes, una tangente y una secante, o dos tangentes es\(\stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2}\) la diferencia de los arcos interceptados.

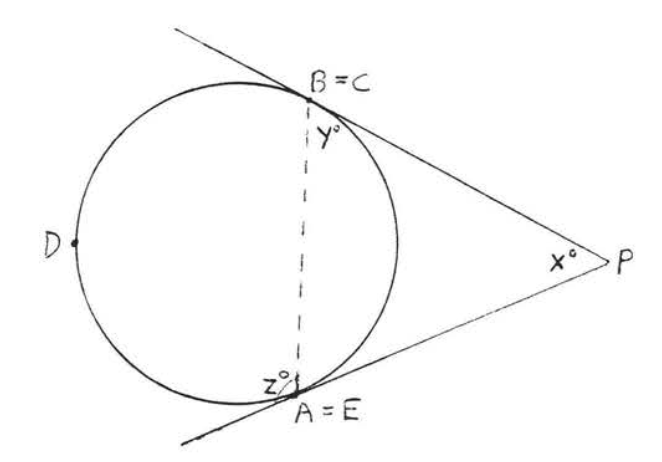

En cada una de las Figuras\(\PageIndex{12}\),\(\PageIndex{13}\) y\(\PageIndex{14}\),\(\angle P \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} (\widehat{CDE} - \widehat{AB})\).

- Prueba

-

En cada caso\(x^{\circ} + y^{\circ} = z^{\circ}\) (porque un ángulo exterior de un triángulo es la suma de los dos ángulos interiores remotos). Por lo tanto\(x^{\circ} = z^{\circ} - y^{\circ}\). Usando Teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\) y\(\PageIndex{4}\) tenemos\(\angle P = x^{\circ} = z^{\circ} - y^{\circ} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{CDE} - \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{AB} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} (\widehat{CDE} - \widehat{AB})\).

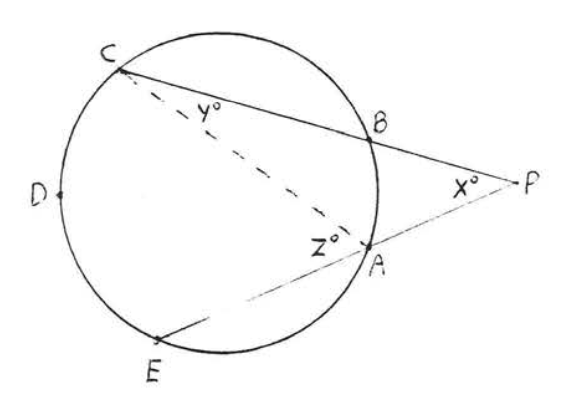

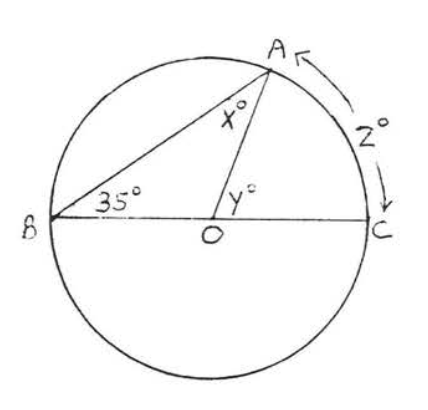

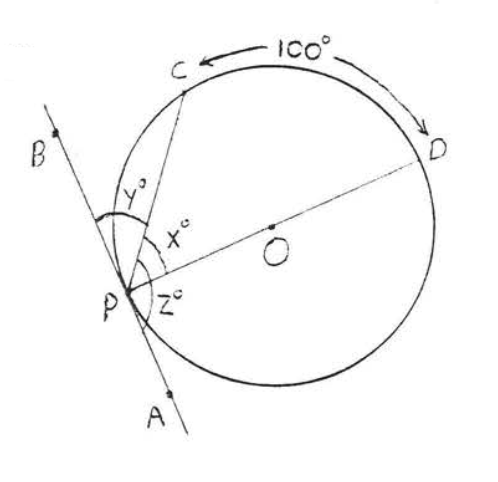

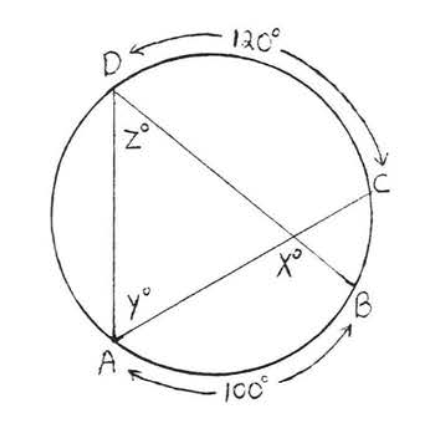

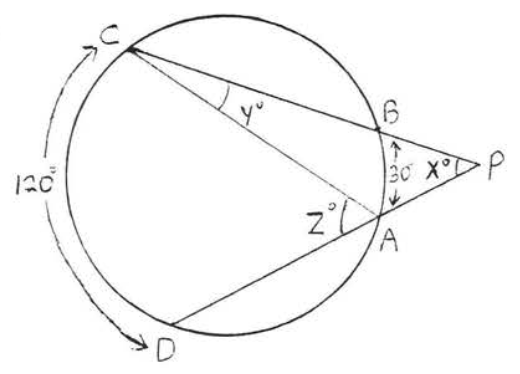

Encuentra\(x, y\) y\(z\):

Solución

Por teorema\(\PageIndex{6}\),\(x^{\circ} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} (\widehat{CD} - \widehat{AB}) \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} (100^{\circ} - 40^{\circ}) = \dfrac{1}{2} (60^{\circ}) = 30^{\circ}\). Por teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\),\(y^{\circ} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{AB} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} (40^{\circ}) = 20^{\circ}\) y\(z^{\circ} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} \widehat{CD} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \dfrac{1}{2} (100^{\circ}) = 50^{\circ}\).

Respuesta:\(x = 30, y = 20, z = 50\).

La práctica de dividir el círculo en 360 grados se remonta a los griegos del siglo II a.C., quienes a su vez pudieron haberlo tomado a los babilonios. El motivo para usar el número 360 no está claro. Podría provenir de una suposición astronómica temprana de que un año consistió en 360 días. Otra explicación se basa en el hecho de que los babilonios utilizaron un sistema de números sexagesimal o base 60 en lugar del sistema decimal o base 10 que usamos hoy en día. Se supone que los babilonios también pueden haber usado 60 como un valor conveniente para el radio de un círculo. Dado que la circunferencia de un círculo es aproximadamente 6 veces el radio (ver siguiente sección), dicho círculo consistiría en 360 unidades.

Problemas

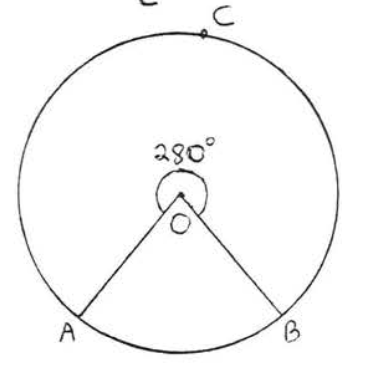

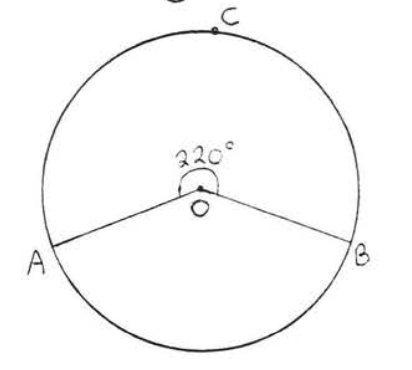

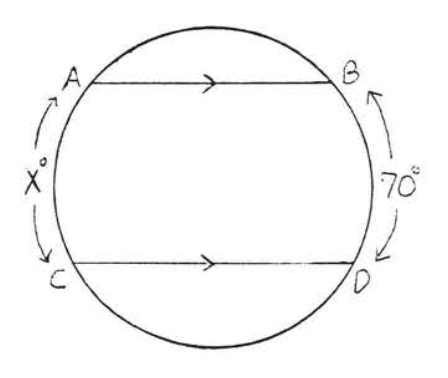

1 - 4. Encuentra el número de grados en arcos\(\widehat{AB}\) y\(\widehat{ACB}\):

1.

2.

3.

4.

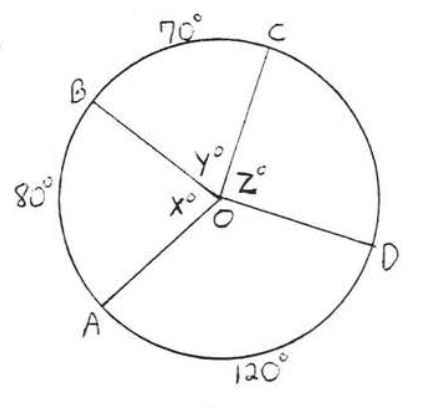

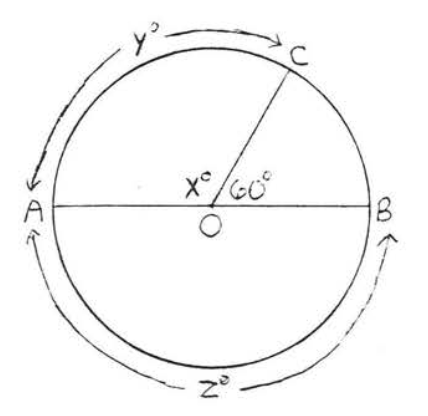

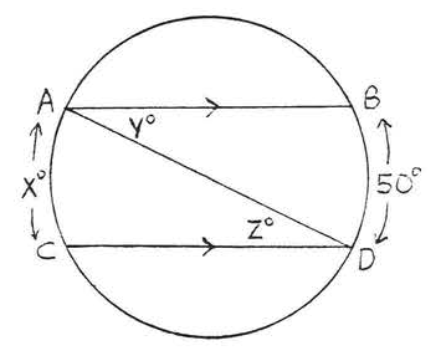

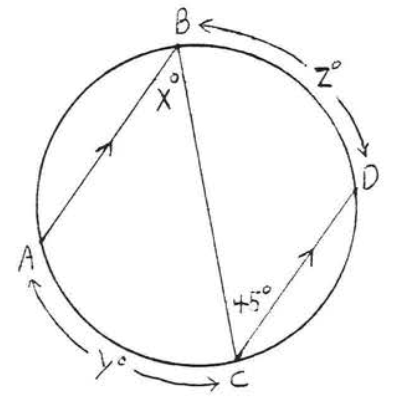

5 - 10. Encuentra\(x, y\) y\(z\):

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

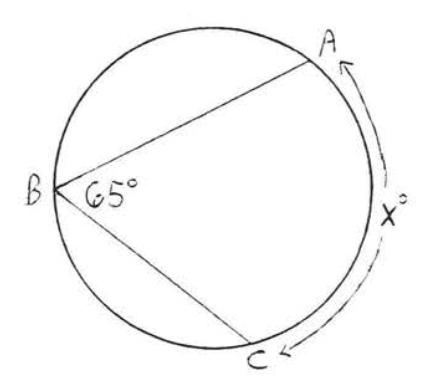

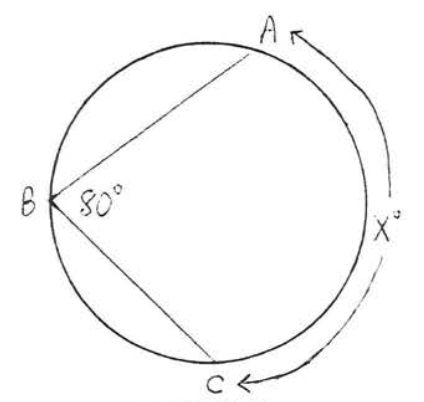

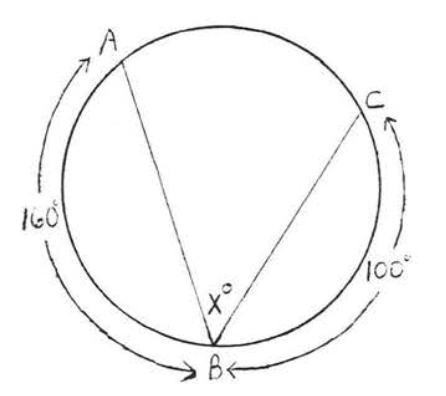

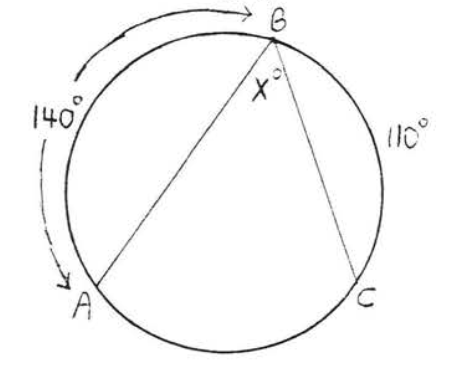

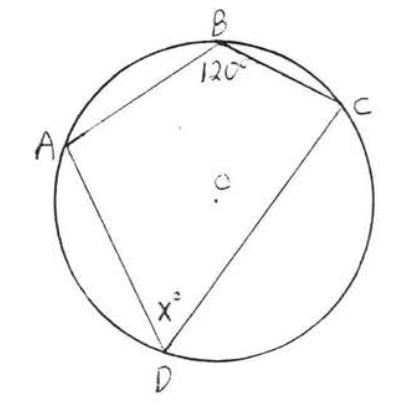

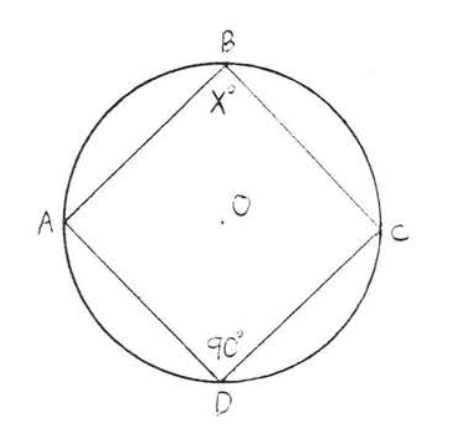

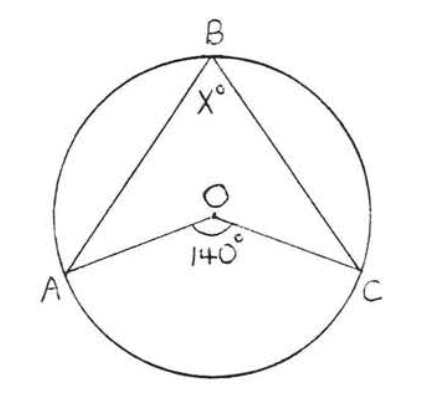

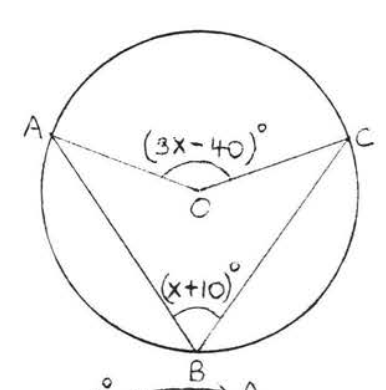

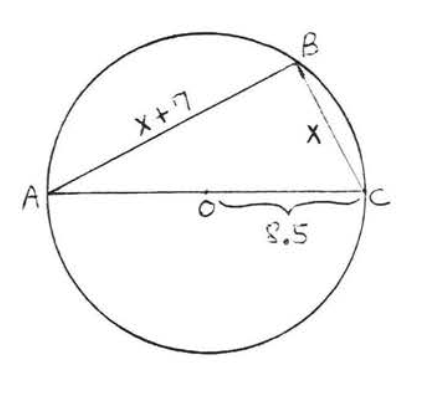

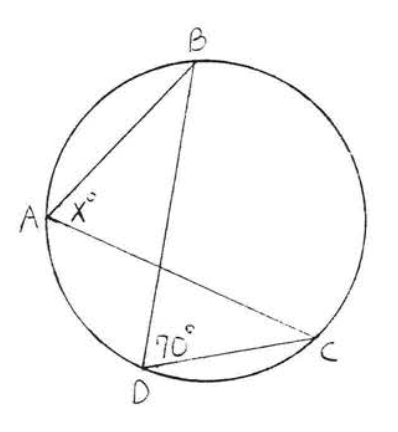

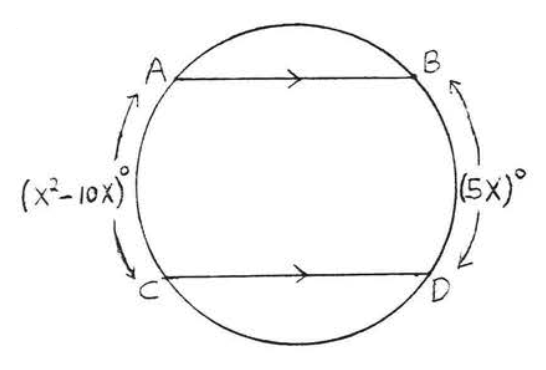

11 - 26. Encuentra\(x\):

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27 - 28. Encuentra\(x, y\) y\(z\):

27.

28.

29 - 30. Encuentra\(x\):

29.

30.

31 - 32. Encuentra\(x, y\) y\(z\):

31.

32.

33 - 34. Encuentra\(x\):

33.

34.

35 - 36. Buscar\(x\),\(y\) y\(z\):

35.

36.

37 - 38. Encuentra\(x\):

37.

38.

39 - 42. Encuentra\(x, y\) y\(z\):

39.

40.

41.

42.

43 - 46. Encuentra\(x\):

43.

44.

45.

46.