6.7: Funciones inversas

- Page ID

- 116498

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Los poetas al revés escriben inversa.

Autor desconocido

Todos los estudiantes de matemáticas tienen experiencia en resolver una ecuación para\(x\). Las funciones inversas son un caso especial de esto.

En Ejemplo\(6.6.6\), se demostró que\(f(x) = 5x − 7\) es una biyección. Una mirada a la prueba revela que la fórmula\((y + 7)/5\) juega un papel clave. La razón por la que esta fórmula es tan importante es que (resolviendo\(x\)) tenemos\[y=5 x-7 \quad \Leftrightarrow \quad x=\frac{y+7}{5} .\]

Para ver esto como una “función inversa”, traducimos al lenguaje de las funciones, dejando que\(g: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) se definan por\(g(y) = (y + 7)/5\). Entonces la aseveración anterior puede ser reafirmada como: (6.7.2)\[y=f(x) \quad \Leftrightarrow \quad x=g(y) .\]

Esto nos dice que\(g\) hace exactamente lo contrario de lo que\(f\) hace: si\(f\) lleva\(x\) a\(y\), entonces\(g\) lleva\(y\) a\(x\). Diremos que\(g\) es la “inversa” de\(f\).

El siguiente ejercicio proporciona una reafirmación de (6.7.2) que se utilizará en la definición oficial de funciones inversas. Sin embargo, usualmente usamos\(A\) para el dominio de una función genérica (y\(B\) para el codominio), por lo que reemplaza las variables\(x\) y\(y\) con\(a\) y\(b\).

Supongamos\(f: A \rightarrow B\) y\(g: B \rightarrow A\). Demuestre que si\[\forall a \in A, \forall b \in B,(b=f(a) \Leftrightarrow a=g(b)) ,\]

entonces

- \(g(f(a))=a \text { for all } a \in A\)y

- \(\text { b) } f(g(b))=b \text { for all } b \in B \text {. }\)

Supongamos

- \(f: A \rightarrow B\), y

- \(g: B \rightarrow A\).

Decimos que\(g\) es la inversa de\(f\) iff:

- \(g(f(a)) = a \text { for all } a \in A\), y

- \(f(g(b))=b \text { for all } b \in B\)

Supongamos\(z: S \rightarrow T\) y\(k: T \rightarrow S\). ¿Qué significa decir que\(k\) es lo inverso de\(z\)?

Solución

Significa que dos cosas son ciertas:

- \(k(z(s)) = s \text { for all } s \in S\), y

- \(z(k(t))=t \text { for all } t \in T .\)

Supongamos\(c: U \rightarrow V\) y\(d: V \rightarrow U\). ¿Qué significa decir que\(d\) es lo inverso de\(c\)?

Se denota\(f\) la inversa de\(f^{−1}\).

Tenga en cuenta que:

- el marido de la esposa de cualquier hombre casado es el hombre mismo, es decir,\[\text { husband }(\text { wife }(m))=m ,\]

y - la esposa del marido de cualquier mujer casada es la mujer misma, es decir,\[\text { wife }(\text { husband }(w))=w .\]

Esto significa que la\(\text {husband}\) función es la inversa de la\(\text {wife}\) función. Es decir,\(\text{wife}^{−1} = \text{ husband.}\)

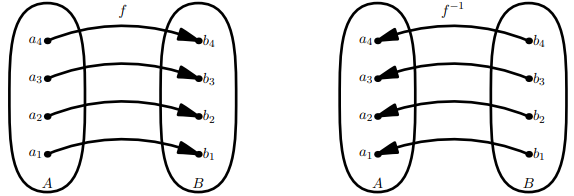

La inversa es fácil de describir en términos de diagramas de flecha. A saber, del hecho de que\[b=f(a) \quad \Leftrightarrow \quad a=f^{-1}(b) ,\]

vemos que\[f \text { has an arrow from } a \text { to } b \Leftrightarrow f^{-1} \text { has an arrow from } b \text { to } a \text {. } .\]

Por lo tanto, el diagrama de flechas de\(f^{−1}\) se obtiene simplemente invirtiendo todas las flechas en el diagrama de flechas de\(f\):

Definir\(f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) y\(g: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) por\(f(x) = 7x − 4\) y\(g(x) = (x + 4)/7\). Verificar que\(g\) sea la inversa de\(f\).

Solución

Baste mostrar:

- \(g(f(x))=x \text { for all } x \in \mathbb{R}\), y

- \(f(g(y))=y \text { for all } y \in \mathbb{R} .\)

- Dado\(x \in \mathbb{R}\), tenemos\[g(f(x))=\frac{f(x)+4}{7}=\frac{(7 x-4)+4}{7}=\frac{7 x}{7}=x .\]

- Dado\(y \in \mathbb{R}\), tenemos\[f(g(y))=7 g(y)-4=7\left(\frac{y+4}{7}\right)-4=(y+4)-4=y .\]

En cada caso, verificar que\(g\) sea la inversa de\(f\).

- \(f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R} \text { is defined bv } f(x)=9 x-6 \text { and } g: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R} \text { is defined by } g(x)=(x+6) / 9 .\)

- \(f: \mathbb{R}^{+} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{+} \text {is defined by } f(x)=x^{2} \text { and } g: \mathbb{R}^{+} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{+} \text {is defined by } g(x)=\sqrt{x} .\)

- \(f: \mathbb{R}^{+} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{+} \text {is defined by } f(x)=1 / x \text { and } g: \mathbb{R}^{+} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{+} \text {is defined by } g(x)=1 / x .\)

- \(f: \mathbb{R}^{+} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{+} \text {is defined by } f(x)=\sqrt{x+1}-1 \text { and } g: \mathbb{R}^{+} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{+} \text {is defined by } g(x)=x^{2}+2 x \text {. }\)

La mayoría de las funciones no tienen una inversa. De hecho, solo las bijecciones tienen una inversa:

Supongamos\(f: A \rightarrow B\). Si\(f\) tiene una inversa\(f^{−1}: B \rightarrow A\), entonces\(f\) es una biyección.

- Prueba

-

Supongamos que hay una función\(f^{−1}: B \rightarrow A\) que es una inversa de\(f\). Entonces

- \(f^{-1}(f(a))=a \text { for all } a \in A\), y

- \(f\left(f^{-1}(b)\right)=b \text { for all } b \in B\).

Deseamos demostrar que\(f\) es una bijección. Esto se deja como un ejercicio para el lector. [Pista: Esto es muy similar a muchas de las pruebas anteriores de que las funciones son bijecciones, pero con la ecuación\(a = f^{−1}(b)\) en lugar de una fórmula explícita para\(a\). Por ejemplo, si\(f(a_{1}) = f(a_{2})\), entonces\(f^{−1} (f(a_{1})) = f^{−1}(f(a_{2}))\). ¿A qué es igual cada lado de esta ecuación?]

- Demostrar que la inversa de una biyección es una biyección.

- Demostrar lo contrario de Ejercicio\(6.7.3\).

- Mostrar que la inversa de una función es única: si\(g_{1}\) y\(g_{2}\) son inversas de\(f\), entonces\(g_{1} = g_{2}\). (Por eso hablamos de lo inverso de\(f\), más que de un inverso de\(f\).)

Si\(f\) es una función que tiene una inversa, entonces es fácil de encontrar\(f^{−1}\) como un conjunto de pares ordenados. A saber,\[f^{-1}=\{(b, a) \mid(a, b) \in f\} .\]

Esto es simplemente una reafirmación del hecho de que\[b=f(a) \Leftrightarrow a=f^{-1}(b)\]

(o el hecho de que el diagrama de flechas de\(f^{−1}\) se obtiene invirtiendo las flechas en el diagrama de flechas de\(f\)).

Demuestra lo contrario del teorema\(6.7.12.\) [Pista: Encuentra\(f^{−1}\) como un conjunto de pares ordenados.]

Supongamos que\(f: A \rightarrow B\) es una biyección. Demostrar que la inversa de\(f^{−1}\) es\(f\). Es decir,\((f^{−1})^{−1} = f\).