2.2: Geometría plana - El área de una elipse

- Page ID

- 112467

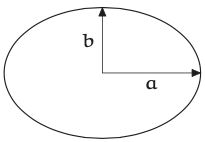

La segunda aplicación de los casos fáciles es desde la geometría plana: el área de una elipse. Esta elipse tiene un eje semimajor\(a\) y un eje semiminor\(b\). Para su área\(A\) considerar a los siguientes candidatos:

(a)\(ab^{2}\) (b)\(a^{2}\) +\(b^{2}\) (c)\(a^{3}/b\) (d) 2ab (e)\(\pi\) ab.

¿Cuáles son los méritos o inconvenientes de cada candidato?

El candidato\(A = ab^{2}\) tiene dimensiones de\(L^{3}\), mientras que un área debe tener dimensiones de\(L^2\). Así ab debe estar equivocado. El candidato\(A = a^2 + b^2\) tiene dimensiones correctas (al igual que los candidatos restantes), por lo que las siguientes pruebas son los casos fáciles de los radios\(a\) y\(b\). Para a, el extremo bajo\(a = 0\) produce una elipse infinitesimalmente delgada con área cero. Sin embargo, cuando\(a = 0\) el candidato\(A = a^{2} + b^{2}\) reduce a\(A = b^{2}\) más bien que a 0; así\(a^2 + b^2\) falla la\(a = 0\) prueba.

El candidato predice\(A = a^3/b\) correctamente el área cero cuando\(a = 0\). Debido a que\(a = 0\) era un caso fácil útil, y las etiquetas de los ejes a y b son casi intercambiables, su contraparte simétrica también\(b = 0\) debería ser un caso fácil útil. También produce una elipse infinitesimalmente delgada con área cero; ay, el candidato\(a^{3}/b\) predice un área infinita, por lo que falla la\(b = 0\) prueba. Quedan dos candidatos.

El candidato se\(A = 2ab\) muestra prometedor. Cuando\(a = 0 \text{ or } b = 0\), las áreas reales y predichas son cero, por lo que\(A = 2ab\) pasa ambas pruebas de casos fáciles. Otras pruebas requieren el tercer caso fácil:\(a = b\). Entonces la elipse 2 se convierte en un círculo con radio a y área\(\pi a\). El candidato\(2ab\), sin embargo, reduce a\(A=2a^2\), por lo que falla la\(a = b\) prueba.

El candidato\(A = \pi ab\) pasa las tres pruebas:\(a = 0, b = 0, \text{ and } a = b\). Con cada prueba aprobatoria, aumenta nuestra confianza en el candidato; y de hecho\(pi ab\) es el área correcta (Problema 2.4).

Problema 2.4 Área por cálculo

Usa la integración para demostrarlo\(A = \pi ab\).

Problema 2.5 Inventar a un candidato aprobador

¿Se puede inventar un segundo candidato para el área que tenga las dimensiones correctas y pase las\(a = 0, b = 0, \text{ and } a = b\) pruebas?

Problema 2.6 Generalización

Adivina el volumen de un elipsoide con radios principales\(a, b, \text{ and } c\).