9.2: Hallar raíces de un polinomio con el TI-84

- Page ID

- 117653

Hemos visto que las raíces son características importantes de un polinomio. Recordemos que las raíces del polinomio\(f\) son aquellas\(x_0\) para las cuales\(f(x_0)=0\). Estas son, por supuesto, precisamente las\(x\) -intercepciones de la gráfica. Por lo tanto, podemos usar la gráfica de un polinomio para encontrar sus raíces como lo hicimos en la sección 9.1.

Encuentra las raíces del polinomio a partir de su gráfica.

- \(f(x)=x^3-7x^2+14x-8\)

- \(f(x)=-x^3+8x^2-21x+18\)

- \(f(x)=x^4+3x^3-x+6\)

- \(f(x)=x^5-3x^4-8x^3+24x^2+15x-45\)

Solución

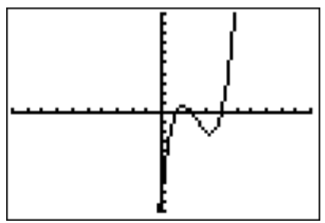

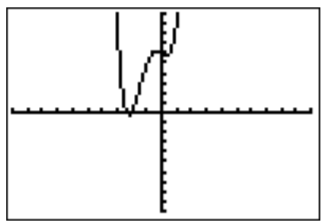

- Comenzamos por graficar el polinomio\(f(x)=x^3-7x^2+14x-8\).

La gráfica sugiere que las raíces están en\(x=1\),\(x=2\), y\(x=4\). Esto se puede verificar fácilmente mirando la tabla de funciones.

Dado que el polinomio es de grado\(3\), no puede haber otras raíces.

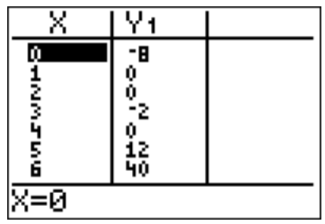

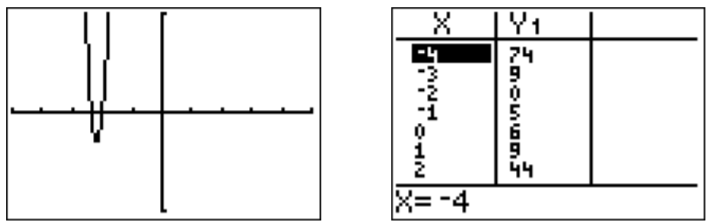

- Graficando\(f(x)=-x^3+8x^2-21x+18\) con la calculadora muestra la siguiente pantalla.

Al hacer zoom en la gráfica se revela que de hecho hay dos raíces,\(x=2\) y\(x=3\), lo que se puede confirmar a partir de la tabla.

Tenga en cuenta, que la raíz\(x=3\) sólo “toca” el\(x\) eje -eje. Esto se debe a que\(x=3\) aparece como una raíz múltiple. En efecto, como\(3\) es una raíz, podemos dividir\(f(x)\) por\(x-3\) sin resto y factificar el cociente resultante para ver que eso

\[f(x)=(x-2)(x-3)(x-3)=(x-2)(x-3)^2 \nonumber \]

Decimos que\(x=3\) es una raíz de multiplicidad\(2\).

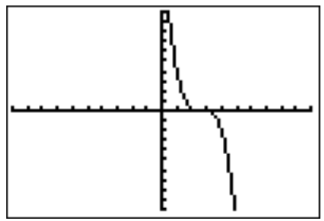

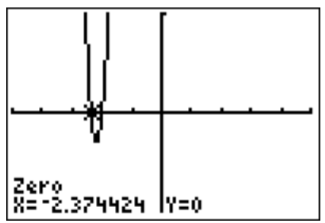

- El gráfico de\(f(x)=x^4+3x^3-x+6\) en la ventana estándar se muestra de la siguiente manera.

Dado que se trata de un polinomio de grado\(4\), todas las características esenciales ya se muestran en la gráfica anterior. Las raíces se pueden ver haciendo zoom en la gráfica.

De la tabla y la gráfica vemos que hay una raíz en\(x=-2\) y otra raíz en el medio\(-3\) y\(-2\). Encontrar el valor exacto de esta segunda raíz puede ser bastante difícil, y diremos más sobre esto en la sección 2 a continuación. En este punto, solo podemos aproximar la raíz con la función “cero” desde el menú “calc”:

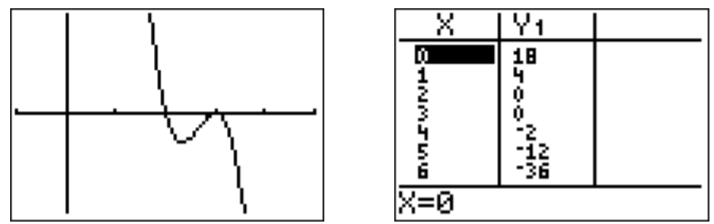

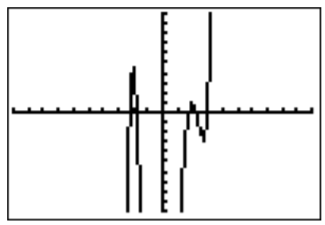

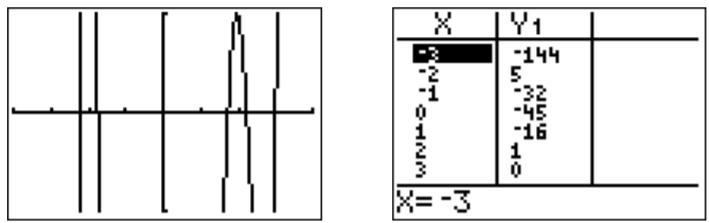

- El gráfico de\(f(x)=x^5-3x^4-8x^3+24x^2+15x-45\) en la ventana estándar se muestra a continuación.

Al hacer zoom en el\(x\) eje -y verificar la tabla se muestra que la única raíz obvia es\(x=3\).

Las otras cuatro raíces son más difíciles de encontrar. Sin embargo, se pueden aproximar usando la función “cero” del menú “calc”.

A menudo será necesario encontrar las raíces de un polinomio cuadrático. Por ello, recordamos la conocida fórmula cuadrática.

Las soluciones de la ecuación\(f(x)=ax^2+bx+c\) para algunos números reales\(a\),\(b\), y\(c\) están dadas por:

\[x_{1}=\dfrac{-b+\sqrt{b^{2}-4 a c}}{2 a}, \quad \text { and } \quad x_{2}=\dfrac{-b-\sqrt{b^{2}-4 a c}}{2 a} \nonumber \]

Podemos combinar las dos soluciones\(x_1\)\(x_2\) y simplemente escribir esto como:

\[\boxed{x_{1 / 2}=\dfrac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^{2}-4 a c}}{2 a}} \nonumber \]

Siempre podemos usar las raíces\(x_1\) y\(x_2\) de un polinomio cuadrático\(f(x)=ax^2+bx+c\) de la fórmula cuadrática y reescribir el polinomio como:

\[\boxed{f(x)=a x^{2}+b x+c=a \cdot\left(x-\frac{-b+\sqrt{b^{2}-4 a c}}{2 a}\right)\left(x-\frac{-b-\sqrt{b^{2}-4 a c}}{2 a}\right)} \nonumber \]