10.3: Reacciones ácido-base à la Brønsted

- Page ID

- 70880

Asegúrese de comprender a fondo las siguientes ideas esenciales que se han presentado anteriormente. Es especialmente importante que conozcas los significados precisos de todos los términos resaltados en el contexto de este tema.

- Explicar la diferencia entre los conceptos Arrhenius y Bronsted-Lowry de ácidos y bases, y dar ejemplos de un ácido y una base en los que el concepto Arrhenius es inaplicable.

- Explique por qué un ion hidrógeno no puede existir en el agua.

- Dada la fórmula de un ácido o base, escribir la fórmula de su conjugado.

- Afirmar la diferencia fundamental entre un ácido fuerte y un ácido débil.

- Describir el efecto nivelador y explicar su origen.

- Anotar los factores que determinan si una solución de una sal será ácida o alcalina.

- Escribir la ecuación para la autoprotólisis de un anfólito dado.

En esta lección desarrollamos este concepto e ilustramos sus aplicaciones a ácidos y bases “fuertes” y “débiles”, enfatizando el tema común de que la química ácido-base es siempre una competencia entre dos bases para el protón. En la sección final, mostramos cómo el concepto de “energía protónica” puede ayudarnos a comprender y predecir la dirección y extensión de los tipos comunes de reacciones ácido-base sin necesidad de cálculos.

Donantes y aceptadores de protones

La teoría más antigua de Arrhenius de ácidos y bases los veía como sustancias que producen iones hidrógeno o iones hidróxido en la disociación. Un concepto tan útil como este ha sido, no pudo explicar por qué el NH 3, que no contiene iones OH —, es una base y no un ácido, por qué una solución de FeCl 3 es ácida, o por qué una solución de Na 2 S es alcalina. Una teoría más general de ácidos y bases fue desarrollada por Franklin en 1905, quien sugirió que el solvente juega un papel central. Según esta visión, un ácido es un soluto que da lugar a un catión (ion positivo) característico del disolvente, y una base es un soluto que produce un anión (ion negativo) que también es característico del disolvente. El más importante de estos solventes es, por supuesto, H 2 O, pero la visión de Franklin extendió el reino de la química ácido-base a sistemas no acuosos como veremos en una lección posterior.

Ácidos y bases Brønsted

En 1923, el químico danés J.N. Brønsted, basado en la teoría de Franklin, propuso que un ácido es un donante de protones; una base es un aceptor de protones. Ese mismo año el químico inglés T.M. Lowry publicó un artículo en el que exponía algunas ideas similares sin producir una definición; en un artículo posterior el propio Lowry señala que Brønsted merece el mayor crédito, pero el concepto sigue siendo ampliamente conocido como la teoría de Brønsted-Lowry.

Ácidos y bases de Brønsted-Lowry

Un ácido es un donante de protones y una base es un aceptor de protones.Estas definiciones llevan una implicación muy importante: una sustancia no puede actuar como un ácido sin la presencia de una base para aceptar el protón, y viceversa. Como ejemplo muy sencillo, consideremos la ecuación que Arrhenius escribió para describir el comportamiento del ácido clorhídrico:

\[HCl \rightarrow H^+ + A^–\]

Esto está bien en lo que va, y los químicos todavía escriben tal ecuación como un atajo. Pero para representar esto de manera más realista como una reacción donador-aceptor de protones, ahora describimos el comportamiento del HCl en el agua por

en el que el ácido HCl dona su protón al aceptor (base) H 2 O.

“Aquí nada nuevo”, podría decirse, señalando que simplemente estamos reemplazando una ecuación más corta por una más larga. Pero considere cómo podríamos explicar la solución alcalina que se crea cuando el gas amoníaco NH 3 se disuelve en agua. Una solución alcalina contiene un exceso de iones hidróxido, por lo que el amoníaco es claramente una base, pero debido a que no hay iones OH — en NH 3, claramente no es una base de Arrhenius. Es, sin embargo, una base Brønsted:

En este caso, la molécula de agua actúa como el ácido, donando un protón a la base NH 3 para crear el ion amonio NH 4 +.

Los ejemplos anteriores ilustran varios aspectos importantes del concepto Brønsted-Lowry de ácidos y bases:

- Una sustancia no puede actuar como un ácido a menos que esté presente un aceptor de protones (base) para recibir el protón;

- Una sustancia no puede actuar como base a menos que esté presente un donante de protones (ácido) para suministrar el protón;

- El agua juega un doble papel en muchas reacciones ácido-base; H 2 O puede actuar como aceptor de protones (base) para un ácido, o puede servir como donante de protones (ácido) para una base (como vimos para el amoníaco.

- El ion hidronio H 3 O + juega un papel central en la química ácido-base de las soluciones acuosas.

Brønsted

Brønsted (1879-1947) fue un químico físico danés. Aunque ahora es conocido principalmente por su teoría donador-aceptor de protones de ácidos y bases (ver su artículo original), publicó numerosos artículos anteriores sobre afinidad química, y más tarde sobre los efectos catalíticos de ácidos y bases en reacciones químicas. En la Segunda Guerra Mundial se opuso a los nazis, y esto llevó a su elección al parlamento danés en 1947, pero no pudo ocupar su asiento por enfermedad y murió más tarde en ese año.

Lowry

Lowry (1874-1936) fue el primer titular de la cátedra de química física en la Universidad de Cambridge. Sus amplios estudios sobre los efectos de los ácidos y bases sobre el comportamiento óptico de los derivados del alcanfor (específicamente, cómo rotan el plano de la luz polarizada) le llevaron a formular una teoría de ácidos y bases similar y simultánea a la de Brønsted.

El ion hidronio

Existe otro problema grave con la visión Arrhenius de un ácido como una sustancia que se disocia en el agua para producir un ion hidrógeno. El ión hidrógeno no es más que un protón, un núcleo desnudo. A pesar de que sólo lleva una sola unidad de carga positiva, esta carga se concentra en un volumen de espacio que sólo es alrededor de una centésima millonésima de grande como el volumen ocupado por el átomo más pequeño. (¡Piensa en un guijarro sentado en medio de un estadio deportivo!) La densidad de carga extraordinariamente alta resultante del protón lo atrae fuertemente a cualquier parte de un átomo o molécula cercana en la que haya un exceso de carga negativa. En el caso del agua, este será el par solitario (no compartido) electrones del átomo de oxígeno; el pequeño protón será enterrado dentro del par solitario y formará un enlace de electrones compartidos (coordenada) con él, creando un ion hidronio, H 3 O +. En cierto sentido, H 2 O está actuando como base aquí, y el producto H 3 O + es el ácido conjugado del agua:

Debido al abrumador exceso de\(H_2O\) molecules in aqueous solutions, a bare hydrogen ion has no chance of surviving in water.

Although other kinds of dissolved ions have water molecules bound to them more or less tightly, the interaction between H+ and H2O is so strong that writing “H+(aq)” hardly does it justice, although it is formally correct. The formula H3O+ more adequately conveys the sense that it is both a molecule in its own right, and is also the conjugate acid of water.

The equation "HA → H+ + A–" is so much easier to write that chemists still use it to represent acid-base reactions in contexts in which the proton donor-acceptor mechanism does not need to be emphasized. Thus it is permissible to talk about “hydrogen ions” and use the formula H+ in writing chemical equations as long as you remember that they are not to be taken literally in the context of aqueous solutions.

Interestingly, experiments indicate that the proton does not stick to a single H2O molecule, but changes partners many times per second. This molecular promiscuity, a consequence of the uniquely small size and mass the proton, allows it to move through the solution by rapidly hopping from one H2O molecule to the next, creating a new H3O+ ion as it goes. The overall effect is the same as if the H3O+ ion itself were moving. Similarly, a hydroxide ion, which can be considered to be a “proton hole” in the water, serves as a landing point for a proton from another H2O molecule, so that the OH– ion hops about in the same way.

Because hydronium- and hydroxide ions can “move without actually moving” and thus without having to plow their way through the solution by shoving aside water molecules as do other ions, solutions which are acidic or alkaline have extraordinarily high electrical conductivities.

Acid-base reactions à la Brønsted

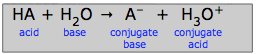

According to the Brønsted concept, the process that was previously written as a simple dissociation of a generic acid HA ("HA → H+ + A–)" is now an acid-base reaction in its own right:

\[HA + H_2O \rightarrow A^- + H_3O^+\]

The idea, again, is that the proton, once it leaves the acid, must end up somewhere; it cannot simply float around as a free hydrogen ion.

Conjugate pairs

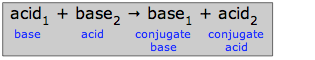

A reaction of an acid with a base is thus a proton exchange reaction; if the acid is denoted by AH and the base by B, then we can write a generalized acid-base reaction as

\[AH + B \rightarrow A^- + BH^+\]

Notice that the reverse of this reaction,

\[BH^+ + A^- \rightarrow B + AH^+\]

is also an acid-base reaction. Because all simple reactions can take place in both directions to some extent, it follows that transfer of a proton from an acid to a base must necessarily create a new pair of species that can, at least in principle, constitute an acid-base pair of their own.

In this schematic reaction, base1 is said to be conjugate to acid1, and acid2 is conjugate to base2. The term conjugate means “connected with”, the implication being that any species and its conjugate species are related by the gain or loss of one proton. The table below shows the conjugate pairs of a number of typical acid-base systems.

|

acid

|

base

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| hydrochloric acid | HCl | Cl– | chloride ion |

| acetic acid | CH3CH2COOH | CH3CH2COO– | acetate ion |

| nitric acid | HNO3 | NO3– | nitrate ion |

| dihydrogen phosphate ion | H2PO4– | HPO4– | monohydrogen phosphate ion |

| hydrogen sulfate ion | HSO4– | SO42– | sulfate ion |

| hydrogen carbonate ("bicarbonate") ion | HCO3– | CO32– | carbonate ion |

| ammonium ion | NH4+ | NH3 | ammonia |

| iron(III) ("ferric") ion | Fe(H2O)63+ | Fe(H2O)5OH2+ | |

| water | H2O | OH– | hydroxide ion |

| hydronium ion | H3O+ | H2O | water |

Strong acids and weak acids

We can look upon the generalized acid-base reaction

as a competition of two bases for a proton:

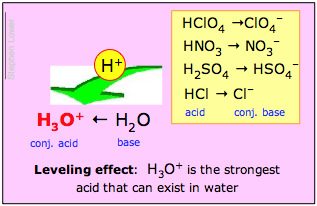

If the base H2O overwhelmingly wins this tug-of-war, then the acid HA is said to be a strong acid. This is what happens with hydrochloric acid and the other common strong "mineral acids" H2SO4, HNO3, and HClO4:

| hydrochloric acid | HCl + H2O → Cl– + H3O+ |

| sulfuric acid | H2SO4 + H2O → HSO4– + H3O+ |

| nitric acid | HNO3 + H2O → NO3– + H3O+ |

| perchloric acid | HClO4 + H2O → ClO4– + H3O+ |

Solutions of these acids in water are really solutions of the ionic species shown in heavy type on the right. This being the case, it follows that what we call a 1 M solution of "hydrochloric acid" in water, for example, does not really contain a significant concentration of HCl at all; the only real a acid present in such a solution is H3O+!

These considerations give rise to two important rules:

- H3O+ is the strongest acid that can exist in water;

- All strong acids appear to be equally strong in water.

The Leveling Effect

The second of these statements is called the leveling effect. It means that although the inherent proton-donor strengths of the strong acids differ, they are all completely dissociated in water. Chemists say that their strengths are "leveled" by the solvent water.

A comparable effect would be seen if one attempted to judge the strengths of several adults by conducting a series of tug-of-war contests with a young child. One would expect the adults to win overwhelmingly on each trial; their strengths would have been "leveled" by that of the child.

Weak acids

Most acids, however, are able to hold on to their protons more tightly, so only a small fraction of the acid is dissociated. Thus hydrocyanic acid, HCN, is a weak acid in water because the proton is able to share the lone pair electrons of the cyanide ion CN– more effectively than it can with those of H2O, so the reaction

\[HCN + H_2O \rightarrow H_3O^+ + CN^–\]

proceeds to only a very small extent. Since a strong acid binds its proton only weakly, while a weak acid binds it tightly, we can say that

Strong acids are "weak" and weak acids are "strong." If you are able to explain this apparent paradox, you understand one of the most important ideas in acid-base chemistry!

|

reaction

|

acid

|

base

|

conjugate acid

|

conjugate base

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| autoionization of water H2O | H2O | H2O | H3O+ | OH– |

| ionization of hydrocyanic acid HCN | HCN | H2O | H3O+ | CN– |

| ionization of ammonia NH3 in water | NH3 | H2O | NH4+ | OH– |

| hydrolysis of ammonium chloride NH4Cl | NH4+ | H2O | H3O+ | NH3 |

| hydrolysis of sodium acetate CH3COO- Na+ | H2O | CH3COO– | CH3COOH | OH– |

| neutralization of HCl by NaOH | HCl | OH– | H2O | Cl– |

| neutralization of NH3 by acetic acid | CH3COOH | NH3 | NH4+ | CH3COO– |

| dissolution of BiOCl (bismuth oxychloride) by HCl | 2 H3O+ | BiOCl | Bi(H2O)3+ | H2O, Cl– |

| decomposition of Ag(NH3)2+ by HNO3 | 2 H3O+ | Ag(NH3)2+ | NH4+ | H2O |

| displacement of HCN by CH3COOH | CH3COOH | CN– | HCN | CH3COO– |

Strong acids have weak conjugate bases

This is just a re-statement of what is implicit in what has been said above about the distinction between strong acids and weak acids. The fact that HCl is a strong acid implies that its conjugate base Cl– is too weak a base to hold onto the proton in competition with either H2O or H3O+. Similarly, the CN– ion binds strongly to a proton, making HCN a weak acid.

Salts of weak acids give alkaline solutions

The fact that HCN is a weak acid implies that the cyanide ion CN– reacts readily with protons, and is thus is a relatively good base. As evidence of this, a salt such as KCN, when dissolved in water, yields a slightly alkaline solution:

CN– + H2O → HCN + OH–

This reaction is still sometimes referred to by its old name hydrolysis ("water splitting"), which is literally correct but tends to obscure its identity as just another acid-base reaction. Reactions of this type take place only to a small extent; a 0.1M solution of KCN is still, for all practical purposes, 0.1M in cyanide ion.

In general, the weaker the acid, the more alkaline will be a solution of its salt. However, it would be going to far to say that "ordinary weak acids have strong conjugate bases." The only really strong base is hydroxide ion, OH–, so the above statement would be true only for the very weak acid H2O.

Strong bases and weak bases

The only really strong bases you are likely to encounter in day-to-day chemistry are alkali-metal hydroxides such as NaOH and KOH, which are essentially solutions of the hydroxide ion. Most other compounds containing hydroxide ions such as Fe(OH)3 and Ca(OH)2 are not sufficiently soluble in water to give highly alkaline solutions, so they are not usually thought of as strong bases.

There are actually a number of bases that are stronger than the hydroxide ion — best known are the oxide ion O2– and the amide ion NH2–, but these are so strong that they can rob water of a proton:

O2– + H2O → 2 OH–

NH2– + H2O → NH3 + OH–

This gives rise to the same kind of leveling effect we described for acids, with hydroxide ion as the strongest base in water.

Hydroxide ion is the strongest base that can exist in aqueous solution.

The most common example of this is ammonium chloride, NH4Cl, whose aqueous solutions are distinctly acidic:

NH4+ + H2O → NH3 + H3O+

Because this (and similar) reactions take place only to a small extent, a solution of ammonium chloride will only be slightly acidic.

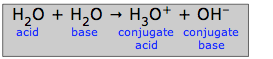

Autoprotolysis

From some of the examples given above, we see that water can act as an acid

CN– + H2O → HCN + OH–

and as a base

NH4+ + H2O → NH3 + H3O+

If this is so, then there is no reason why "water-the-acid" cannot donate a proton to "water-the-base":

This reaction is known as the autoprotolysis of water.

Chemists still often refer to this reaction as the "dissociation" of water and use the Arrhenius-style equation H2O → H+ + OH–as a kind of shorthand. As discussed in the previous lesson, this process occurs to only a tiny extent. It does mean, however, that hydronium and hydroxide ions are present in any aqueous solution.

Ammonia and Sulfuric acid

Other liquids also exhibit autoprotolysis with the most well-known example is liquid ammonia:

2 NH3 → NH4+ + NH2–

Even pure liquid sulfuric acid can play the game:

2 H2SO4→ H3SO4+ + HSO4–

Each of these solvents can be the basis of its own acid-base "system", parallel to the familiar "water system".

Ampholytes

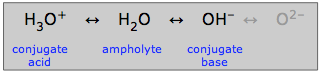

Water, which can act as either an acid or a base, is said to be amphiprotic: it can "swing both ways". A substance such as water that is amphiprotic is called an ampholyte.

As indicated here, the hydroxide ion can also be an ampholyte, but not in aqueous solution in which the oxide ion cannot exist.

It is of course the amphiprotic nature of water that allows it to play its special role in ordinary aquatic acid-base chemistry. But many other amphiprotic substances can also exist in aqueous solutions. Any such substance will always have a conjugate acid and a conjugate base, so if you can recognize these two conjugates of a substance, you will know it is amphiprotic.

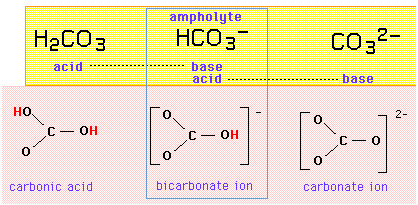

The carbonate system

For example, the triplet set {carbonic acid, bicarbonate ion, carbonate ion} constitutes an amphiprotric series in which the bicarbonate ion is the ampholyte, differing from either of its neighbors by the addition or removal of one proton:

If the bicarbonate ion is both an acid and a base, it should be able to exchange a proton with itself in an autoprotolysis reaction:

\[HCO_3^– + HCO_3^– \rightarrow H_2CO_3 + CO_3^{2-}\]

Carbonic Acid

Your very life depends on the above reaction! CO2, a metabolic by-product of every cell in your body, reacts with water to form carbonic acid H2CO3 which, if it were allowed to accumulate, would make your blood fatally acidic. However, the blood also contains carbonate ion, which reacts according to the reverse of the above equation to produce bicarbonate which can be safely carried by the blood to the lungs. At this location the autoprotolysis reaction runs in the forward direction, producing H2CO3 which loses water to form CO2 which gets expelled in the breath. The carbonate ion is recycled back into the blood to eventually pick up another CO2 molecule.

If you can write an autoprotolysis reaction for a substance, then that substance is amphiprotic.