6.1: ¿Qué es un ácido y una base?

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Propiedades generales de ácidos y bases

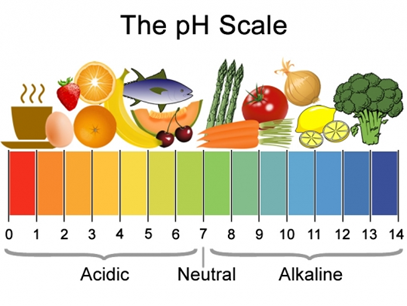

Comúnmente encontramos ácidos y bases en nuestros alimentos, algunos alimentos son ácidos y otros básicos (alcalinos), como se ilustra en la Fig. 6.1.1.

Las propiedades generales de ácidos y bases son las siguientes.

- Los ácidos tienen un sabor agrio, por ejemplo, los cítricos tienen un sabor fuente debido al ácido cítrico y al ácido ascórbico, es decir, la vitamina C, en ellos. Sustancias básicas (alcalinas), por otro lado, tienen un sabor amargo.

- Las sustancias básicas (alcalinas) se sienten sucias, mientras que las sustancias ácidas pueden picar.

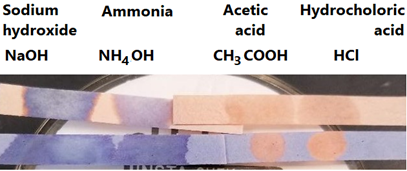

- Los ácidos se vuelven papel tornasol azul para leer pero no cambian el color del papel tornasol rojo. Las bases se vuelven azules al papel tornasol rojo pero no cambian el color del papel tornasol azul, como se ilustra en la Fig. 6.1.2.

- El indicador de fenolftaleína se vuelve incoloro en ácido y se vuelve rosado en solución básica, como se ilustra en la Fig. 6.1.3.

- Los ácidos y bases se neutralizan entre sí. El ácido clorhídrico se encuentra en el estómago que ayuda a la digestión. El exceso de ácido clorhídrico puede causar quemaduras ácidas, los antiácidos como la leche de magnesia son bases que ayudan a neutralizar el exceso de ácido en el estómago.

Definición de Arrhenius de ácidos y bases

La definición más temprana de ácidos y bases es la definición de Arrhenius que establece que:

- Un ácido es una sustancia que forma iones hidrógeno H + cuando se disuelve en agua, y

- Una base es una sustancia que forma iones hidróxido OH - cuando se disuelve en agua.

o ejemplo, el ácido clorhídrico es un ácido porque forma H + cuando se disuelve en agua.

HCl(g) Water ⟶H+(aq)+Cl−(aq)

De igual manera, el NaOH es una base porque forma OH, cuando se disuelve en agua.

NaOH(s) Water ⟶Na+(aq)+OH−(aq)

Tenga en cuenta que el ion hidrógeno H + no existe en la realidad. Se une con moléculas de agua y existe como ion hidronio H 3 O + (aq).

H+(aq)+H2O→H3O+(aq)

Sin embargo, H + (aq) a menudo se escribe en lugar de (H 3 O + (aq).

Nombrar ácidos y bases de Arrhenius

En el Cuadro 1 se enumeran los nombres y fórmulas de algunos de los ácidos comunes y sus aniones.

- Los nombres terminan con la palabra “ácido”.

- Si el anión no es un oxianión, entonces agrega el prefijo hydro- al nombre del anión y cambia la última sílaba del nombre del anión a —ic. Por ejemplo, Cl - es un ion cloruro, y HCl es ácido clorhídrico.

- Si el anión es un oxianión con la última sílaba —ate, cambia la última sílaba por —ic. No utilice el prefijo hydro-, pero agregue la última palabra “ácido”. Si hay un prefijo per- en el nombre del oxianión, conserve el prefijo en el nombre ácido. Por ejemplo, NO 3 - es un nitrato, y HNO 3 es ácido nítrico. Otro ejemplo, ClO 4 - es un perclorato, y HClO 3 es ácido perclórico.

- Si el anión es un oxianión con la última sílaba —ite, cambia la última sílaba por —ous. No utilice el prefijo hydro-, pero agregue la última palabra “ácido”. Si hay un prefijo hipo- en el nombre del oxianión, conserve el prefijo en el nombre ácido. Por ejemplo, NO 2 - es nitrito, y HNO 2 es ácido nitroso. Otro ejemplo, ClO - es hipoclorito, y HClO es ácido hipocloroso.

|

Fórmula ácida |

Nombre ácido |

Anión |

Nombre del anión |

|---|---|---|---|

|

HCl |

Ácido clorhídrico |

Cl - |

Cloruro |

|

HBr |

Ácido bromhídrico |

Br - |

Bromuro |

|

HOLA |

Ácido yodhídrico |

I - |

yoduro |

|

HCN |

Ácido cianhídrico |

CN - |

Cianuro |

|

HNO 3 |

Ácido nítrico |

NO 3 - |

Nitrato |

|

HNO 2 |

Ácido nitroso |

NO 2 - |

Nitrito |

|

H 2 SO 4 |

Ácido sulfúrico |

SO 4 2 - |

Sulfato |

|

H 2 SO 3 |

Ácido sulfuroso |

SO 3 2 - |

Sulfito |

|

H 2 CO 3 |

Ácido carbónico |

CO 3 - |

Carbonato |

|

CH 3 COOH |

Ácido acético |

CH 3 COO - |

Acetato |

|

H 3 PO 4 |

Ácido fosfórico |

PO 4 3 - |

Fosfato |

|

H 3 PO 3 |

Ácido fosforoso |

PO 3 3 - |

Fosfito |

|

HClO 4 |

Ácido perclórico |

ClO 4 - |

Perclorato |

|

HClO 3 |

Ácido clórico |

ClO 3 - |

Clorato |

|

HClO 2 |

Ácido cloroso |

ClO 2 - |

Clorita |

|

HClO |

Ácido hipocloroso |

ClO - |

Hipoclorito |

En el Cuadro 2 se enumeran los nombres y fórmulas de algunas de las bases comunes de Arrhenius.

Las bases Arrhenius son compuestos iónicos de metal e ion hidróxido, y su nombre comienza con el nombre del elemento metálico seguido del nombre del anión, es decir, hidróxido. Por ejemplo, el NaOH es hidróxido de sodio.

|

Fórmula |

Nombre |

|---|---|

|

LiOh |

Hidróxido de litio |

|

NaOH |

Hidróxido de sodio |

|

KOH |

Hidróxido de potasio |

|

Ca (OH) 2 |

Hidróxido de calcio |

|

Sr (OH) 2 |

Hidróxido de estroncio |

|

Ba (OH) 2 |

Hidróxido de bario |