2.7: Números Complejos

- Page ID

- 84303

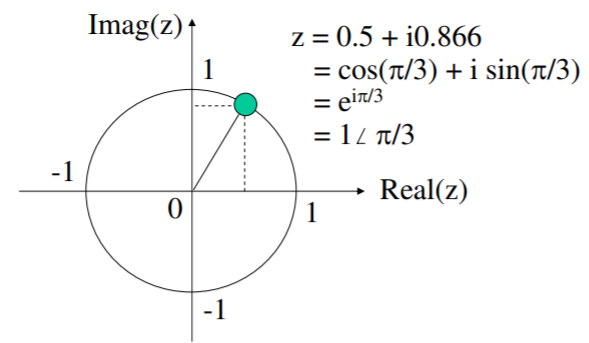

El número complejo\(z = x + iy\) se interpreta de la siguiente manera: la parte real es\(x\), la parte imaginaria es\(y\), y\(i = \sqrt{−1}\) (imaginaria). El teorema de Demoivre conecta complejo\(z\) con lo exponencial complejo. Afirma eso\(cos \, \theta + i \, sin \, \theta = e^{i \theta}\), y así podemos visualizar cualquier número complejo en el plano bidimensional, donde los ejes son la parte real y la parte imaginaria. Eso decimos\(Re(e^{i \theta}) = cos \, \theta\), y\(Im(e^{i \theta}) = sin \, \theta\), para denotar las partes reales e imaginarias de un exponencial complejo. De manera más general,\(Re(z) = x\) y\(Im(z) = y\).

.png)

Un número complejo tiene una magnitud y un ángulo:\(|z| = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2}\), y arg\((z) = arctan2(y, x)\). Podemos referirnos a la\([x, y]\) descripción de\(z\) coordenadas cartesianas, mientras que la descripción [magnitud, ángulo] se denomina coordenadas polares. Este último suele escribirse como\(z = |z| \angle\) arg\((z)\). Las reglas aritméticas para dos números complejos\(z_1\) y\(z_2\) son las siguientes:

\[\begin{align*} z_1 + z_2 &= (x_1 + x_2) + i (y_1 + y_2) \\[4pt] z_1 - z_2 &= (x_1 - x_2) + i (y_1 - y_2) \\[4pt] z_1 * z_2 &= |z_1| |z_2| \angle \arg (z_1) + \arg (z_2) \\[4pt] z_1 / z_2 &= \dfrac{|z_1|} {|z_2|} \angle \arg (z_1) - \arg (z_2) \end{align*}\]

Obsérvese que, como se ha dado, la suma y resta se expresan de manera más natural en coordenadas cartesianas, y la multiplicación y división son más limpias en coordenadas polares.