4.10: Resistencia difusa

- Page ID

- 86505

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

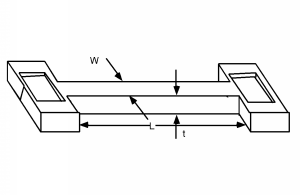

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)A veces, en un diseño de circuito, necesitaremos una resistencia. Esto generalmente se hace ya sea con poli o con una difusión (se muestra en la Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\)). Si tomamos nuestro tanque n o difusión similar tipo n, podríamos hacer una tira larga y estrecha de él, y usarla como resistencia. Siempre y cuando mantengamos el sustrato a tierra, y cualquier voltaje en la resistencia mayor que tierra, la unión n-p será polarizada inversa y la resistencia estará aislada del sustrato. Ahora todos sabemos que\[\begin{array}{l} R &= \frac{\rho L}{A} \\ &= \frac{L}{nq \mu tW} \end{array}\]

Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\): Una resistencia difusa

Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\): Una resistencia difusa

El único problema es, ¿qué es\(n\) para una resistencia difusa? Un vistazo rápido al gráfico que muestra la concentración de portadores en función de la profundidad después de una difusión muestra que cuando hacemos una difusión, no\(n\) es una constante, sino que varía a medida que bajamos a la oblea. Tendremos que hacer algún tipo de integral, asumiendo muchas resistencias paralelas, delgadas, ¡cada una con una concentración de portador diferente! Esto no es muy satisfactorio.

De hecho, es tan insatisfactorio que los ingenieros de CI han llegado con una mejor resistencia de descripción que una que involucra\(n\) y\(\mu\). Tenga en cuenta que podríamos escribir la ecuación\(\PageIndex{1}\) como\[R = \frac{1}{nq \mu t} \frac{L}{W}\]

Definimos la primera fracción (que contiene la concentración de portador, espesor, etc.) como la resistencia laminar\(R_{s}\) de la difusión. Si bien esto puede predecirse más o menos, generalmente también es un valor medido después de la fabricación. \[R_{s} \equiv \frac{1}{nq \mu t}\]

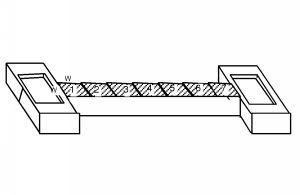

\(R_{s}\)tiene unidades de\(\mathrm{"Ohms}/\mathrm{square"}\), y probablemente estés tentado a preguntar “¿por cuadrado qué?”. Bueno, puede ser cualquier cuadrado en absoluto, medido en centímetros, micrómetros, kilómetros, etc., ya que todo lo que realmente necesitamos saber es\(R_{s}\) y la relación longitud-ancho de la estructura de resistencia para encontrar la resistencia de una resistencia. No necesitamos saber qué unidades se utilizan para medir el largo y el ancho, siempre y cuando sean iguales para ambas. Por ejemplo, si la resistencia en la Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\) tiene una resistividad laminar de\(50 \ \Omega / \mathrm{square}\), entonces bloqueando la resistencia en cuadrados que están\(W\) en ambas dimensiones, vemos que la resistencia es de 7 cuadrados de largo (Figura\(\PageIndex{2}\)) y así su resistencia se da como:\[\begin{array}{l} R &= 50 \ \left(\frac{\Omega}{\mathrm{square}}\right) 7 \ \ (\mathrm{squares}) \\ &= 350 (\Omega) \end{array}\]

Figura\(\PageIndex{2}\): Contando los cuadrados

Figura\(\PageIndex{2}\): Contando los cuadrados