1.5: Coordenadas polares

- Page ID

- 109906

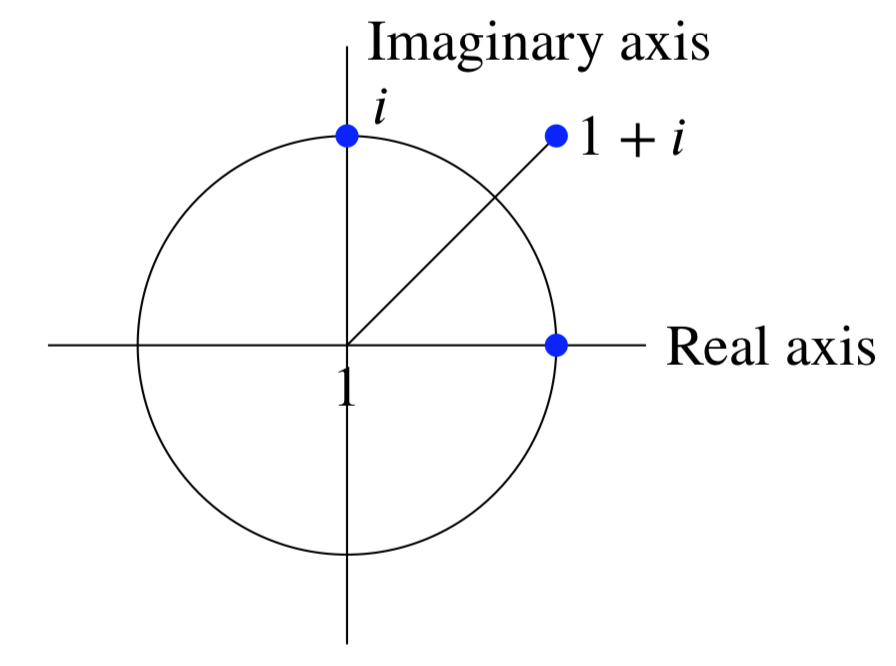

En las figuras anteriores hemos marcado la longitud\(r\) y el ángulo polar\(\theta\) del vector desde el origen hasta el punto\(z = x + iy\). Estas son las mismas coordenadas polares que viste anteriormente. Hay una serie de sinónimos para ambos\(r\) y\(\theta\)

\(r =|z|\)= magnitud = longitud = norma = valor absoluto = módulo

\(\theta = \text{arg} (z)\) = argumento de\(z\) = ángulo polar de\(z\)

Deberías poder visualizar las coordenadas polares pensando en la distancia\(r\) desde el origen y el ángulo\(\theta\) con el\(x\) eje -eje.

Hagamos una tabla de\(z\),\(r\) y\(\theta\) para algunos números complejos. Observe que no\(\theta\) está definido de manera única ya que siempre podemos agregar un múltiplo de\(2\pi\) a\(\theta\) y seguir estando en el mismo punto en el plano.

\(\begin{array} {ccll} {z = a + bi} & {r} & {\theta} & { } \\ {1} & {1} & {0, 2\pi , 4\pi , ...} & {\text{Argument = 0, means}\, z \,\text{is along the } x\text{-axis}} \\ {i} & {1} & {\pi /2, \pi /2 + 2\pi ...} & {\text{Argument = } \pi /2, \text{ means}\, z \,\text{is along the } y\text{-axis}} \\ {1 + i} & {\sqrt{2}} & {\pi /4 , \pi /4 + 2\pi ...} & {\text{Argument = } \pi /4, \text{ means}\, z \,\text{is along the ray at } 45^{\circ} \text{to the } x\text{-axis}} \end{array}\)

Cuando queremos tener claro a qué valor de\(\theta\) se entiende, especificaremos una rama de arg. Por ejemplo,\(0 \le \theta < 2\pi\) o\(-\pi < \theta \le \pi\). Esto se discutirá con mucho más detalle en las próximas semanas. Hacer un seguimiento cuidadoso de las ramas de arg resultará ser uno de los requisitos clave del análisis complejo.