2.4: El punto en el infinito

- Page ID

- 109677

Por definición el plano complejo extendido\(= C \cup \{\infty\}\). Es decir, tenemos un punto en el infinito para pensarlo en un sentido limitante descrito de la siguiente manera.

Una secuencia de puntos\(\{z_n\}\) va al infinito si\(|z_n|\) va al infinito. Este “punto al infinito” se aproxima en cualquier dirección que vayamos. Todas las secuencias mostradas en Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\) están creciendo, por lo que todas van al (mismo) “punto al infinito”.

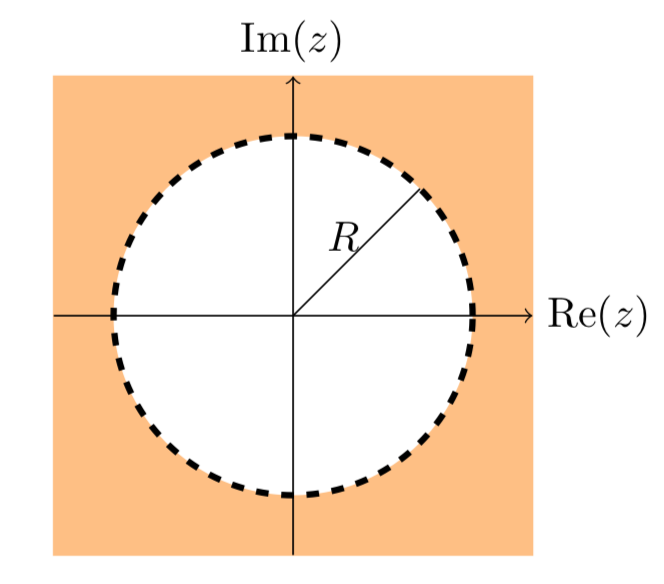

Si dibujamos un círculo grande alrededor de 0 en el plano, entonces llamamos a la región fuera de este círculo barrio de infinito (Figura\(\PageIndex{2}\)).

Límites que implican infinito

La idea clave es\(1/\infty = 0\). Con esto queremos decir

\[\lim_{z \to \infty} \dfrac{1}{z} = 0\]

Entonces tenemos los siguientes hechos:

- \(\lim_{z \to z_0} f(z) = \infty \Leftrightarrow \lim_{z \to z_0} 1/f(z) = 0\)

- \(\lim_{z \to \infty} = w_0 \Leftrightarrow \lim_{z \to 0} f(1/z) = w_0\)

- \(\lim_{z \to \infty} = \infty \Leftrightarrow \lim_{z \to 0} \dfrac{1}{f(1/z)} = 0\)

\(\lim_{z \to \infty} e^z\)no se define porque tiene valores diferentes si vamos al infinito en diferentes direcciones, por ejemplo tenemos\(e^z = e^x e^{iy}\) y

\(\lim_{x \to -\infty} e^x e^{iy} = 0\)

\(\lim_{x \to +\infty} e^x e^{iy} = \infty\)

\(\lim_{y \to +\infty} e^x e^{iy}\)no se define, ya que\(x\) es constante, por lo que\(e^x e^{iy}\) bucles en un círculo indefinidamente.

Mostrar\(\lim_{z \to \infty} z^n = \infty\) (para\(n\) un entero positivo).

Solución

Tenemos que demostrar que\(|z^n|\) se hace grande a medida que\(|z|\) se hace grande. Escribe\(z = Re^{i \theta}\), entonces

\[|z^n| = |R^n e^{in \theta}| = R^n = |z|^n \nonumber\]

Proyección estereográfica desde la esfera de Riemann

Una forma de visualizar el punto en\(\infty\) es mediante el uso de una esfera de Riemann (unidad) y la proyección estereo-gráfica asociada. La figura\(\PageIndex{4}\) muestra una esfera cuyo ecuador es el círculo unitario en el plano complejo.

La proyección estereográfica de la esfera al plano se logra dibujando la línea secante desde el polo norte\(N\) a través de un punto de la esfera y viendo dónde se cruza con el plano. Esto da una correspondencia 1-1 entre un punto en la esfera\(P\) y un punto en el plano complejo\(z\). Es fácil ver mostrar que la fórmula para la proyección estereográfica es

\[P = (a, b, c) \mapsto z = \dfrac{a}{1 - c} + i \dfrac{b}{1 - c}.\]

El punto\(N = (0, 0, 1)\) es especial, las líneas secantes de\(N\) a través\(P\) se convierten en líneas tangentes a la esfera en la\(N\) que nunca se cruzan con el plano. Consideramos\(N\) el punto en el infinito.

En la figura anterior, la región fuera del círculo grande a través del punto\(z\) es un barrio de infinito. Corresponde a la pequeña tapa circular alrededor\(N\) de la esfera. Es decir, ¡la pequeña gorra alrededor\(N\) es un barrio del punto en el infinito en la esfera!

La figura\(\PageIndex{4}\) muestra otra versión común de proyección estereográfica. En esta figura la esfera se asienta con su polo sur en el origen. Seguimos proyectando usando líneas secantes del polo norte.