10.3: Ejemplos importantes

- Page ID

- 118314

la función\(A \to A\) definida por\(a \mapsto a\)

la función de identidad en el set\(A\)

Una función de identidad es siempre una biyección.

la función\(A \to X\) definida por\(a \mapsto a\)

las funciones\(A \times B \to A\) y\(A \times B \to B\) definidas por\((a,b) \mapsto a\) y\((a,b) \mapsto b\)

la función de proyección sobre el primer factor\(A\) en el producto cartesiano\(A \times B\)

la función de proyección sobre el segundo factor\(B\) en el producto cartesiano\(A \times B\)

Considerar\((\dfrac{1}{2},\pi) \in \mathbb{Q} \times \mathbb{R}\text{.}\) Entonces

\ begin {align*} p_ {\ mathbb {Q}}\ left (\ dfrac {1} {2},\ pi\ right) & =\ dfrac {1} {2}, & p_ {\ mathbb {R}}\ left (\ dfrac {1} {2},\ pi\ right) & =\ pi\ text {.} \ end {alinear*}

Extender.

Por supuesto, podemos definir de manera similar una función de proyección sobre un producto cartesiano con cualquier número de factores. Escribir

significa la función de proyección sobre el\(i^{th}\) factor\(A_i\) en el producto cartesiano

Alternativamente, podemos escribir

para esta función.

Una proyección siempre es suryectiva (excepto posiblemente cuando uno o más de los factores en el producto cartesiano es el conjunto vacío).

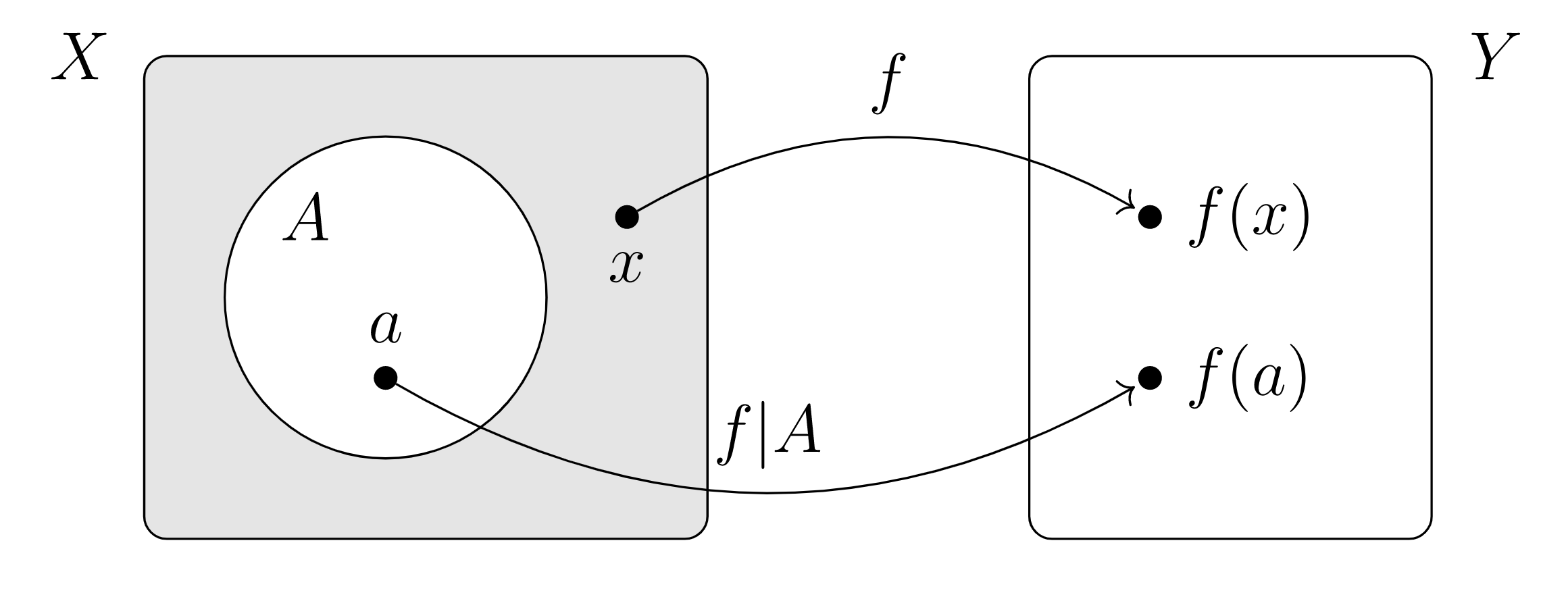

la función “inducida”\(A \to Y\) creada a partir de la función\(f: X\rightarrow Y\) y subconjunto\(A \subseteq X\) “olvidando” todos los elementos de\(X\) que no se encuentran en\(A\)

restricción de función\(f: X\rightarrow Y\) a subconjunto\(A \subseteq X\)

notación de restricción de dominio alternativo

notación de restricción de dominio alternativo

Para\(f: \mathbb{Z} \rightarrow \mathbb{N}\text{,}\)\(f(m) = \vert m \vert \text{,}\) nosotros tenemos\(f \vert _{\mathbb{N}} = \id_{\mathbb{N}}\text{.}\)

Considerar función\(f: X\rightarrow Y\) y subconjunto\(A \subseteq X\text{.}\)

- Si\(f\) es inyectable, ¿es\(f \vert _A\) inyectable?

- Si\(f \vert _A\) es inyectable, ¿debe\(f\) ser inyectable?

- Contesta las dos preguntas anteriores sustituyendo “inyectiva” por “suryectiva”.

El concepto de restringir el dominio hace innecesaria nuestra imagen conceptual previamente definida de una función en un subconjunto: para función\(f: X\rightarrow Y\) y subconjunto\(A \subseteq X\text{,}\) la imagen de\(f\) on\(A\) es la misma que la imagen de la restricción\(f \vert _A\text{.}\)

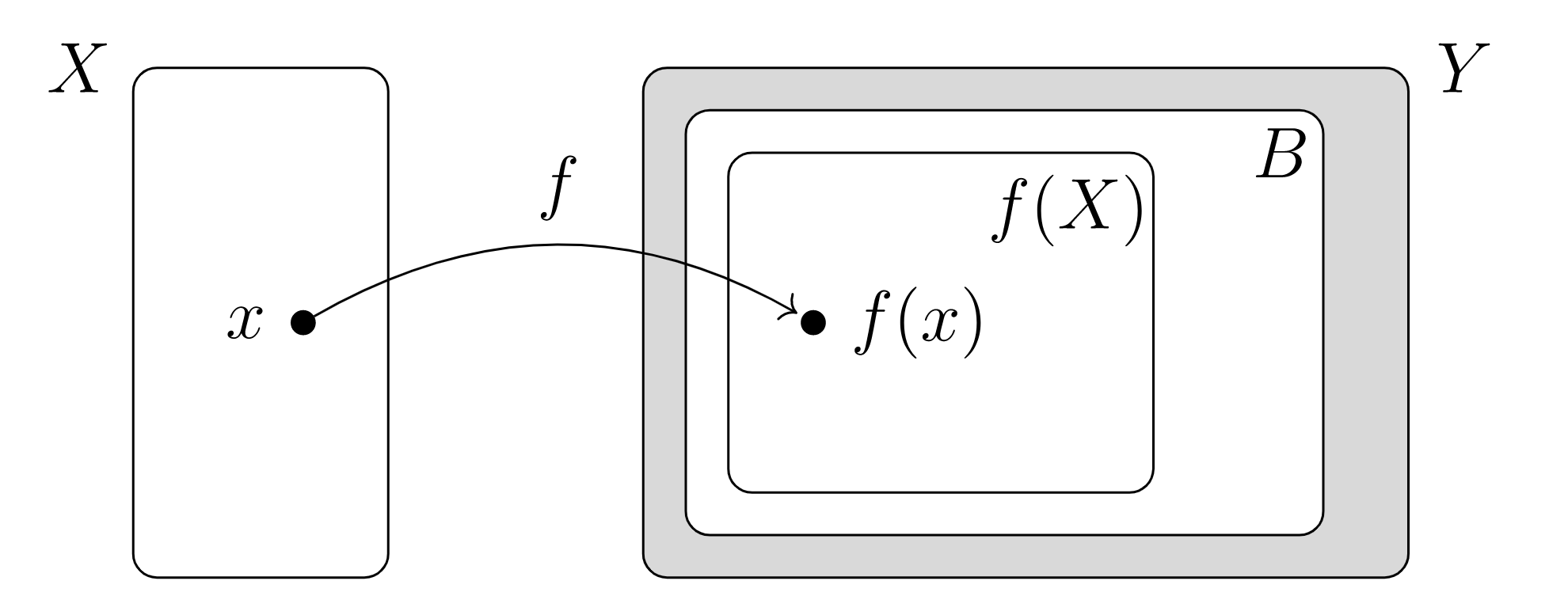

la función “inducida”\(X \to B\) creada a partir de la función\(f: X\rightarrow Y\) y subconjunto\(B \subseteq Y\) por “olvidarse” de todos los elementos de\(Y\) que no se encuentran en\(B\text{,}\) donde\(B\) debe contener la imagen de\(f\)

Considerar\(f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\text{,}\)\(f(x) = x^2\text{.}\) Sería más preciso escribir\(f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}_{\geq 0} \\text{,}\) ya que\(x^2 \ge 0\) para todos\(x \in \mathbb{R}\text{.}\)

Si restringimos el codominio hasta el conjunto de imágenes,\(f(X)\text{,}\) el mapa resultante siempre\(f : X \rightarrow f(X) \) es suryectiva. En particular, si\(f: X \xrightarrow Y\) es inyectivo, entonces restringiendo el codominio podemos obtener una biyección\(f : X \rightarrow f(X) \text{.}\)

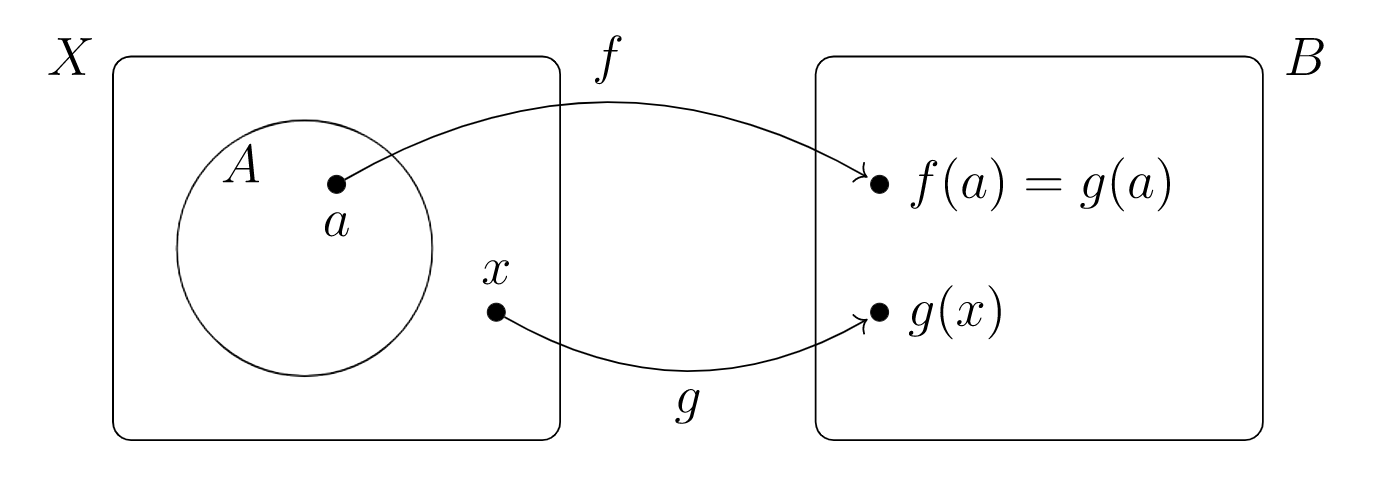

relativo a la función\(f: A \rightarrow B\) y superestablecer\(X \supseteq A\text{,}\) una función\(g(a) = f(a)\) para\(g: X \rightarrow B\) que para todos\(a \in A\)

La condición que define la función de extensión del concepto se puede afirmar más sucintamente como que requiere función\(g: X \rightarrow B\) con\(A \subseteq X\) satisfacer\(g \vert _A = f\text{.}\)

Escribir\(\text{flr}:\mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}\) para significar la función floor: para entrada real\(x\text{,}\) la salida\(\text{flr} (x)\) se define como el mayor entero que es menor o igual a\(x\text{.}\) Usualmente escribimos

\ begin {ecuación*}\ texto {flr} (x) =\ lpiso x\ rpiso\ texto {.} \ end {equation*}

Como cada entero es menor o igual a sí mismo, tenemos\(\text{flr} (z) = z\) para cada\(z \in \mathbb{Z}\text{.}\) Esto dice que la función floor es una extensión de la función de identidad\(\id_{\mathbb{Z}}\text{.}\)

Una de las formas más comunes de extender una función a un dominio más grande es elegir un valor constante apropiado en el codominio para asignarlo a todas las entradas “nuevas” en el dominio ampliado.

relativo a la función\(f: A \rightarrow Z\) y el superconjunto\(X \supseteq A\text{,}\) donde\(Z\) es un conjunto de “números” que contiene un elemento cero, la función de extensión\(g: X \rightarrow Z\) definida por

\ begin {ecuación*} g (x) =\ begin {cases} f (x)\ text {,} & x\ in X\ text {,}\\ 0\ text {,} &\ text {de lo contrario.} \ end {cases}\ end {ecuación*}

Definir\(\widetilde{\id}_{\mathbb{Z}} : \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}\) por

\ begin {ecuation*} {\ Widetilde {\ id}} _ {\ mathbb {Z}} (x) =\ begin {cases} x\ text {,} & x\ in\ mathbb {Z}\ text {,}\\ 0\ text {,} &\ text {de lo contrario.} \ end {cases}\ end {equation*}

Entonces\(\widetilde{\id}_{\mathbb{Z}}\) es la extensión por cero de la función de identidad\(\id_{\mathbb{Z}}\text{.}\)

- Comparar.

-

El ejemplo\(\PageIndex{4}\) también implicaba una extensión de la función de identidad\(\id_{\mathbb{Z}}\) — ¿era una extensión por cero?