10.4: Composición de funciones

- Page ID

- 118308

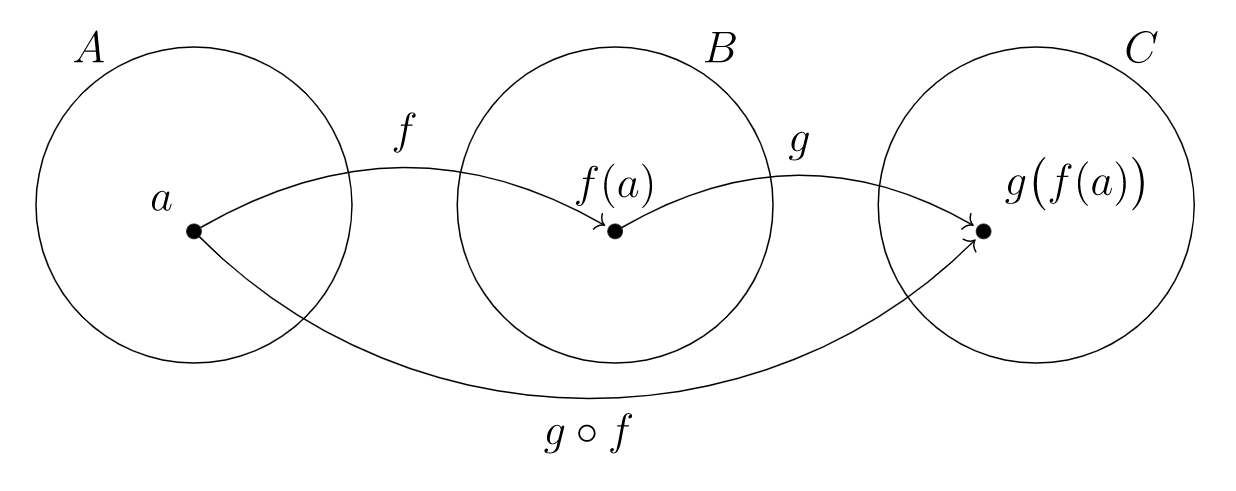

una función\(A \to C\) creada a partir de funciones dadas\(f: A \rightarrow B\) y\(g: B \rightarrow C\) por\(a \mapsto g(f(a))\)

la composición de las funciones\(f: A \rightarrow B\) y\(g: B \rightarrow C\text{,}\) para que\(g \circ f: A\rightarrow C\) por\((g \circ f)(a) = g(f(a))\)

Considerar las funciones

\ begin {align*} f\ colon\ mathbb {R} &\ a\ mathbb {R} _ {\ geq 0}, & g\ colon\ mathbb {R} _ {\ geq 0} &\ a\ mathbb {R} _ _ {\ geq 0},\\ x &\ mapsto x^2, & x &\ mapsto\ sqrt {x},\ end align{ *}

Entonces tenemos

\ begin {alinear*} g\ circ f\ colon\ mathbb {R} &\ a\ mathbb {R} _ {\ geq 0},\\ x &\ mapsto\ sqrt {x^2} =\ vert x\ vert. \ end {alinear*}

La notación para la composición de funciones\(f\) e\(g\) implica una inversión de orden, así que escribimos\(g \circ f\text{.}\) Esto es para que cuando usamos esta notación con notación input-output\((g \circ f)(a)\text{,}\) la notación nos recuerda que primero se\(f\) debe aplicar a la entrada\(a\text{,}\) y luego \(g\)se aplica al resultado\(f(a)\text{.}\)

En general,\(f \circ g \ne g \circ f\text{.}\) Usualmente, uno de los dos ni siquiera está definido, porque dominios y codominios de\(f\) y\(g\) no necesariamente coincidirán en ambos órdenes. Y cuando ambos están definidos, los dos órdenes diferentes de composición suelen tener diferentes dominios y codominios.

Considerar funciones

\ begin {align*} f\ colon\ mathbb {N} &\ a\ mathbb {N}, & g\ colon\ mathbb {N} &\ a\ mathbb {N},\\ n &\ mapsto n^2, & n &\ mapsto n + 1. \ end {align*}

Entonces, ambos\(f \circ g: \mathbb{N} \rightarrow \mathbb{N}\) y\(g \circ f: \mathbb{N} \rightarrow \mathbb{N}\) se definen. Pero no son iguales, como

\ begin {alinear*} (f\ circ g) (n) & = (n+1) ^2 = n^2+2n+1, & (g\ circ f) (n) & = n^2+1. \ end {alinear*}

Considerar funciones

\ begin {align*}\ text {sqrt}\ colon\ mathbb {N} &\ a\ mathbb {R}, &\ text {flr}\ colon\ mathbb {R} &\ a\ mathbb {Z},\\ n &\ mapsto\ sqrt {n}, & x &\ mapsto\ lpiso x\ rpiso. \ end {align*}

(Ver Ejemplo 10.3.4 para una descripción de la\(\text{flr}\) función.)

Entonces,\(\text{flr} \circ \text{sqrt} : \mathbb{N} \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}\) se define, con

\ begin {ecuación*} (\ text {flr}\ circ\ text {sqrt}) (n) =\ lfloor\ sqrt {n}\ rfloor\ text {.} \ end {ecuation*}

Pero no\(\text{sqrt} \circ \text{flr}\) está definido, ya que el codominio de\(\text{flr}\) no coincide con el dominio de\(\text{sqrt} \text{.}\) En particular,\(\text{flr}\) a veces devolverá una salida negativa, y no podemos usar tal salida como entrada en\(\text{sqrt} \text{.}\)

Considerar funciones\(f: A \rightarrow B\) y\(g: B \rightarrow C\text{.}\)

Si\(g \circ f\) es inyectivo, ¿alguna o ambas son\(f,g\) necesariamente inyectables?

Responda la misma pregunta que la anterior con “inyectiva” reemplazada por “suryectiva”.

Demostrar que si ambos\(f\) y\(g\) son biyectivos, entonces la composición también\(g \circ f\) es biyectiva.

Por supuesto, podemos componer cualquier número de funciones.

Reconsideremos la función definida por algoritmo en el Ejemplo 10.1.3. Como la descripción de la función implicaba un algoritmo de varios pasos, deberíamos ser capaces de romper los pasos involucrados en sus propias funciones, luego recrear las funciones originales como una composición.

En primer lugar, definir\(\text{abs} : \mathscr{P}( \mathbb{Z}) \rightarrow \mathscr{P}( \mathbb{N})\) por

\ begin {ecuación*}\ texto {abs} (X) =\ {\ vert x\ vert\;\ vert x\ in X\}\ texto {.} \ end {equation*}

A continuación, defina\(min : \mathscr{P}( \mathbb{N}) \rightarrow \mathbb{N}\) para que\(\text{min}(X)\) genere el número mínimo en conjunto de entrada\(X\text{,}\) y salidas\(0\) en caso\(X = \emptyset\text{.}\)

Por último, definir\(f: \mathbb{N} \rightarrow \mathbb{N}\) por\(f(n) = 2 n + 1\text{.}\)

Cada una de estas funciones representa un paso en el algoritmo definiendo la función en el Ejemplo 10.1.3, pero para recrear esa función necesitamos componer las funciones en el orden correcto: escribir\(\varphi = f \circ \text{min} \circ \text{abs}\text{,}\) para que

\ begin {ecuation*}\ varphi (X) = 2\ text {min} (\ text {abs} (X)) + 1\ end {equation*}

calcula el mismo resultado para un conjunto\(X\) de entrada que el algoritmo descrito en el Ejemplo 10.1.3.