10.5: Inversa

- Page ID

- 118309

Supongamos que\(f: A\rightarrow B\) es una función. Por definición,\(f\) asocia un elemento de\(B\) a cada elemento de\(A\text{.}\) A veces queremos revertir este proceso: dado un elemento\(b \in B\text{,}\) podemos determinar un elemento\(a \in A\) tal que\(f(a) = b\text{?}\) Empezaremos a responder a esta pregunta encontrando primero todos los posibles “resultados inversos” a partir de elementos en subconjuntos de\(B\text{.}\)

el conjunto de todos los elementos de dominio\(a \in A\) para la función\(f: A\rightarrow B\) para la que el elemento de salida correspondiente\(f(a)\) se encuentra en el subconjunto\(C\) del codominio

la imagen inversa del subconjunto\(C \subseteq B\) bajo la función\(f: A\rightarrow B\text{,}\) para que

\ comenzar {ecuación*} f^ {-1} (C) =\ {a\ en A\ vert f (a)\ en C\}\ final {ecuación*}

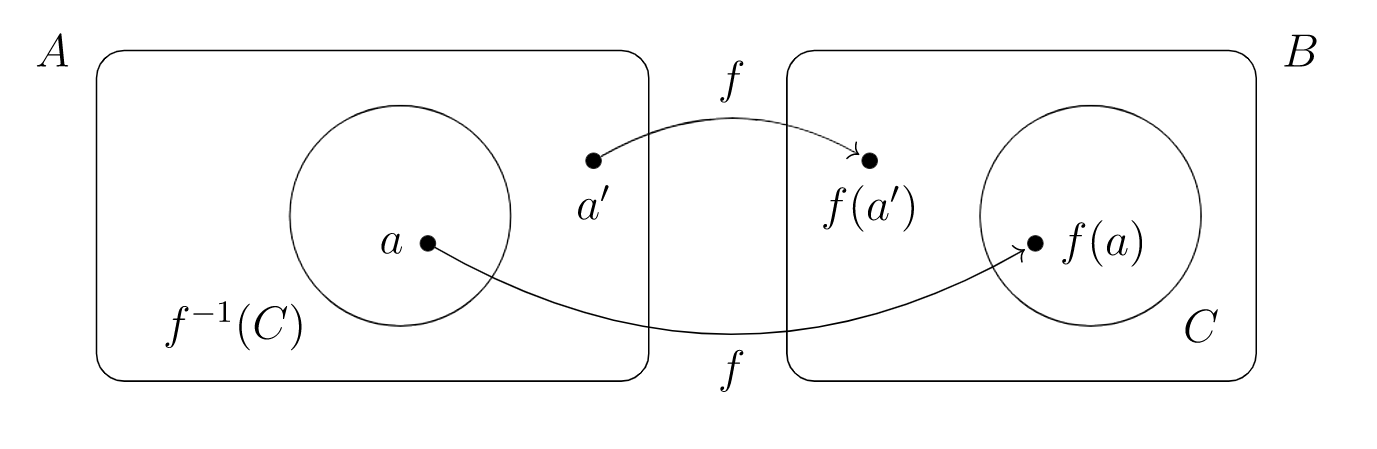

Al igual que en la figura anterior,\(f^{-1}(C)\) recoge todos aquellos elementos de\(A\) cuyas imágenes bajo\(f\) tierra en su interior\(C\text{.}\)

Considerar\(f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\text{,}\)\(f(x) = \sin x\text{.}\)

Entonces

\ begin {ecuación*} f^ {-1} (\ {-1,0,1\}) =\ izquierda\ {\ dfrac {m\ pi} {2}\ vert m\ in\ mathbb {Z}\ derecha\}\ end {ecuación*}

porque

\ begin {ecuation*}\ sin\ left (\ dfrac {m\ pi} {2}\ right)\ end {ecuación*}

será igual\(0\) cuando\(m\) es par y será igual\(1\) o\(-1\) cuando\(m\) es impar, y ningún otro valor de entrada producirá salidas de\(0\text{,}\)\(1\text{,}\) o\(-1\text{.}\)

Sin embargo,

\ begin {ecuación*} f^ {-1} (\ {y\ in\ mathbb {R}\ rightarrow y\ gt 1\}) =\ emptyset\ end {ecuación*}

porque no hay valores de entrada para seno que produzcan un valor de salida mayor que\(1\text{.}\)

Ahora volvamos a la cuestión de intentar revertir una relación input-output\(f(a) = b\text{:}\) el conjunto\(f^{-1}\bbrac{\{b\}}\) recoge todos los posibles candidatos para la imagen inversa de\(b\text{.}\)

la imagen inversa\(f^{-1}(\{b\})\text{,}\) que consiste en todos los elementos de dominio\(a \in A\) para los cuales\(f(a) = b\)

notación simplificada para significar la imagen inversa del elemento\(b\)

Esto nos da una manera de asociar a un elemento\(b \in B\) un conjunto\(f^{-1} (b)\) de elementos de\(A\text{.}\)

Cuando esta asociación nos\(b \mapsto f^{-1} (b)\) da una función\(f^{-1} : B \rightarrow A\text{?}\)

Hay dos formas posibles de que esto no nos dé una función.

- Supongamos que hay un elemento\(b \in B\) tal que el conjunto\(f^{-1} (b)\) contiene (al menos) dos elementos distintos\(a_1,a_2\text{.}\) Entonces en general no hay manera de elegir entre\(f^{-1} (b) = a_1\) y\(f^{-1} (b) = a_2\text{.}\) Por lo tanto, si no\(f\) es inyectivo, la función no\(f^{-1} : B \rightarrow A\) está bien definida.

- Supongamos que hay un elemento\(b \in B\) tal que\(f^{-1} (b) = \emptyset \text{.}\) Entonces no hay ningún elemento del\(A\) que podamos asignar a\(f^{-1} (b)\text{.}\) Por lo tanto, si no\(f\) es suryectiva, la función\(f^{-1} : B \rightarrow A\) está indefinida en algunos elementos de\(B\text{.}\)

Entonces parece que necesitaremos una función para que sea biyectiva para poder revertir la regla input-output para obtener una función inversa.

para una función biyectiva\(f\text{,}\) la función inversa se asocia a cada elemento de codominio\(f\) del elemento de dominio único correspondiente que lo produce a través de\(f\)

la función inversa\(f^{-1} : B \rightarrow A\) para la función biyectiva de\(f: A\rightarrow B\text{,}\) modo que para\(b \in B\) nosotros hemos\(f^{-1} (b)\) definido como el elemento único\(a \in A\) tal que\(f(a) = b\)

La función\(f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\text{,}\)\(f(x) = x^3\text{,}\) es biyectiva y tiene inversa\(f^{-1}(x) = x^{\dfrac{1}{3}}\text{.}\)

Volviendo de nuevo a la biyección\(\varphi: \Sigma \rightarrow B\) encontrada en el Ejemplo 10.2.4 y Ejemplo 10.2.6, donde

\ begin {align*}\ Sigma & =\ {a, b,\ ldots, z\}, & B & =\ {1, 2,\ ldots, 26\},\ end {align*}

la función inversa\(\varphi ^{-1} : B \rightarrow \Sigma\) asocia a cada número\(1 \le b \le 26\) la letra correspondiente en esa posición del alfabeto. Por ejemplo,\(\varphi^{-1} (11) = \text{k} \text{.}\)

La función\(g:\mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\text{,}\)\(g(x) = x^2\text{,}\) no tiene una inversa ya que no es biyectiva. Sin embargo, la función de\(h:\mathbb{R}_{\geq 0}: \mathbb{R}_{\geq 0}\text{,}\)\(h(x) = x^2\text{,}\) manera que\(h = g\vert _{\mathbb{R}_{\geq 0}}\) pero con codominio también restringido a la imagen de\(g\text{,}\) tiene inversa\(h^{-1}(x) = \sqrt{x}\text{.}\)

Si\(f\) es biyectiva, entonces así es\(f^{-1}\text{,}\) y\(f^{-1}\) es la función única\(B \to A\) tal que tanto

\ begin {alinear*} f^ {-1}\ circ f & =\ id_a, & f\ circ f^ {-1} & =\ id_b\ texto {.} \ end {alinear*}

Demostrar que si\(f\) es biyectiva entonces así es\(f^{-1}\text{,}\) y\((f^{-1})^{-1} = f\text{.}\)