2.4: Ángulo recto

- Page ID

- 114578

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

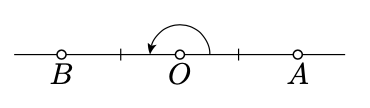

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Si\(\measuredangle AOB = \pi\), decimos que\(\angle AOB\) es un ángulo recto. Obsérvese que por la Proposición 2.3.2, si\(\angle AOB\) es una recta, entonces también lo es\(\angle BOA\).

Nosotros dice que el punto\(O\) se encuentra entre los puntos\(A\) y\(B\), si\(O \ne A\),\(O \ne B\), y\(O \in [AB]\).

El ángulo\(AOB\) es recto si y solo si\(O\) se encuentra entre\(A\) y\(B\).

- Prueba

-

Por la Proposición 2.2.2, podemos suponer que\(OA = OB = 1\).

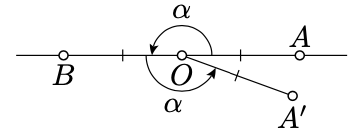

“Si” parte. Asumir\(O\) mentiras entre\(A\) y\(B\). Set\(\alpha = \measuredangle AOB\).

Aplicando Axioma IIIa, obtenemos una media línea\([OA')\) tal que\(\alpha = \measuredangle BOA'\). Por la Proposición 2.2.2, podemos asumir eso\(OA' = 1\). Según Axioma IV,

\(\triangle AOB \cong \triangle BOA'\).

Supongamos que\(f\) denota el movimiento correspondiente del plano; es decir,\(f\) es un movimiento tal que\(f(A) = B\),\(f(O) = O\), y\(f(B) = A'\).

Entonces

\(O = f(O) \in f(AB) = (A'B)\).

Por lo tanto, ambas líneas\((AB)\) y\((A'B)\) contienen\(B\) y\(O\). Por Axioma II,\((AB) = (A'B)\).

Por la definición de la línea,\((AB)\) contiene exactamente dos puntos\(A\) y\(B\) en la distancia 1 de\(O\). Desde\(OA' = 1\) y\(A' \ne B\), lo conseguimos\(A = A'\).

Por Axioma IIIb y Proposición 2.3.1, lo conseguimos

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {2 \cdot \alpha} & = & {\measuredangle AOB + \measuredangle BOA' =} \\ {} & = & {\measuredangle AOB + \measuredangle BOA \equiv} \\ {} & equiv & {\measuredangle AOA =} \\ {} & = & {0} \end{array}\]

Por lo tanto, por el Ejercicio 1.8.1,\(\alpha\) es 0 o\(\pi\).

Ya que\([OA) \ne [OB)\), tenemos eso\(\alpha \ne 0\), ver Ejercicio 2.3.1. Por lo tanto,\(\alpha = \pi\).

“Sólo si” parte. Supongamos que\(\measuredangle AOB = \pi\). Considera la línea\((OA)\) y elige un punto\(B'\) sobre\((OA)\) para que\(O\) quede entre\(A\) y\(B'\).

Desde arriba, tenemos eso\(\measuredangle AOB' = \pi\). Aplicando Axioma IIIa, lo conseguimos\([OB) = [OB')\). En particular,\(O\) se encuentra entre\(A\) y\(B\).

Un triángulo\(ABC\) se llama degenerado si\(A, B\), y\(C\) se encuentra en una línea. El siguiente corolario es solo una reformulación del Teorema 2.4.1.

Un triángulo es degenerado si y sólo si uno de sus ángulos es igual\(\pi\) o 0. Además, en un triángulo degenerado las medidas del ángulo son 0, 0 y\(\pi\).

Ejercicio\(\PageIndex{1}\)

Mostrar que tres puntos distintos\(A, O\), y\(B\) se encuentran en una línea si y sólo si

\(2 \cdot \measuredangle AOB \equiv 0\).

- Pista

-

Aplicar la Proposición 2.3.1, Teorema 2.4.1 y Ejercicio 1.8.1.

Ejercicio\(\PageIndex{2}\)

Dejar\(A, B\) y\(C\) ser tres puntos distintos de\(O\). \(B, O\)Muéstralo y\(C\) acuéstate en una línea si y solo si

\(2 \cdot \measuredangle AOB \equiv 2 \cdot \measuredangle AOC\).

- Pista

-

Axioma IIIb,\(2 \cdot \measuredangle BOC \equiv 2 \cdot \measuredangle AOC - 2 \cdot \measuredangle AOB = 0\). Por el Ejercicio 1.8.1, implica que\(\measuredangle BOC\) es 0 o\(\pi\). Queda por aplicar Exercsie 2.3.1 y Teorema 2.4.1 respectivamente en estos dos casos.

Ejercicio\(\PageIndex{3}\)

Demostrar que hay un triángulo no degenerado.

- Contestar

-

Fijar dos puntos\(A\) y\(B\) proporcionados por Axioma I.

Arreglar un número real\(0 < \alpha < \pi\). Por Axioma IIIa hay un punto\(C\) tal que\(\measuredangle ABC = \alpha\). Utilice la Proposición 2.2.1 para mostrar que no\(\triangle ABC\) es degenerado.