7.6: Método de coordenadas

- Page ID

- 114398

El siguiente ejercicio es importante; demuestra que nuestra definición axiomática concuerda con la definición del modelo.

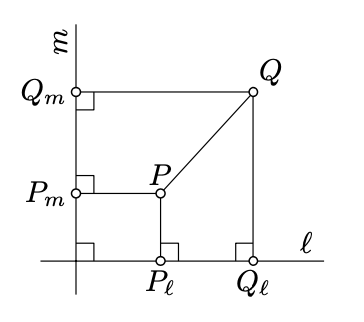

Dejar\(\ell\) y\(m\) ser líneas perpendiculares en el plano euclidiano. Dado un punto\(P\), vamos\(P_{\ell}\) y\(P_m\) denotan los puntos del pie de\(P\) on\(\ell\) y\(m\) respectivamente.

- Demostrar que para cualquier\(X \in \ell\) y\(Y \in m\) hay un punto único\(P\) tal que\(P_{\ell} = X\) y\(P_m = Y\).

- Demuestre eso\(PQ^2 = P_{\ell}Q_{\ell}^2 + P_m Q_m^2\) para cualquier par de puntos\(P\) y\(Q\).

- Concluir que el plano es isométrico a\((\mathbb{R}^2, d_2)\).

- Pista

-

(a). Utilizar la singularidad de la línea paralela (Teorema 7.1.1).

b). Usa Lema 7.5.1 y el teorema de Pitágoras (Teorema 6.2.1)

Una vez resuelto este ejercicio, podemos aplicar el método de coordenadas para resolver cualquier problema en la geometría del plano euclidiano. Este método es poderoso y universal; se desarrollará más en el Capítulo 18.

Utilizar el Ejercicio\(\PageIndex{1}\) para dar una prueba alternativa del Teorema 3.5.1 en el plano euclídeo.

Es decir, probar que dados los números reales\(a, b\), y\(c\) tal que

\(0 < a \le b \le c \le a + b\),

hay un triángulo\(ABC\) tal que\(a = BC\),\(b = CA\), y\(c = AB\).

- Pista

-

Establecer\(A = (0, 0), B = (c, 0)\), y\(C = (x, y)\). Claramente,\(AB = c\),\(AC^2 = x^2 + y^2\) y\(BC^2 = (c - x)^2 + y^2\).

Queda por demostrar que existe un par de números reales\((x, y)\) que satisfagan el siguiente sistema de ecuaciones:

\(\begin{cases} b^2 = x^2 + y^2 \\ a^2 = (c- x)^2 + y^2 \end{cases}\)

si\(0 < a \le b \le c \le a + c\).

Considera dos puntos distintos\(A = (x_A, y_A)\) y\(B = (x_B, y_B)\) en el plano de coordenadas. Mostrar que la bisectriz perpendicular a\([AB]\) es descrita por la ecuación

\(2 \cdot (x_B - x_A) \cdot x + 2 \cdot (y_B - y_A) \cdot y = x_B^2 + y_B^2 - x_A^2 - y_B^2\).

Concluye que la línea se puede definir como un subconjunto del plano de coordenadas del siguiente tipo:

- Soluciones de una ecuación\(a \cdot x + b \cdot y = c\) para algunas constantes\(a, b\), y\(c\) tal que\(a \ne 0\) o\(b \ne 0\).

- El conjunto de puntos\((a \cdot t + c, b \cdot t + d)\) para algunas constantes\(a, b, c\), y\(d\) tal que\(a \ne 0\) o\(b \ne 0\) y todos\(t \in \mathbb{R}\).

- Pista

-

Tenga en cuenta que\(MA = MB\) si y solo si

\((x - x_A)^2 + (y - y_A)^2 = (x - x_B)^2 + (y - y_B)^2\)

donde\(M = (x, y)\). Para probar la primera parte, simplificar esta ecuación. Para las piezas restantes, use que cualquier línea sea una bisectriz perpendicular a algún segmento de línea.