14.3: El producto vectorial

- Page ID

- 69860

El producto vectorial de dos vectores es un vector definido como

\[\mathbf{u}\times \mathbf{v}=|\mathbf{u}| |\mathbf{v}| \mathbf{n} \sin\theta \nonumber\]

donde\(\theta\) está de nuevo el ángulo entre los dos vectores, y\(\mathbf{n}\) es el vector unitario perpendicular al plano formado por\(\mathbf{u}\) y\(\mathbf{v}\). La dirección del vector\(\mathbf{n}\) viene dada por la regla de la derecha. Extiende tu mano derecha y apunta tu dedo índice en la dirección de\(\mathbf{u}\) (el vector en el lado izquierdo del\(\times\) símbolo) y tu dedo índice en la dirección de\(\mathbf{v}\). La dirección de\(\mathbf{n}\), que determina la dirección de\(\mathbf{u}\times \mathbf{v}\), es la dirección de tu pulgar. Si quieres revertir la multiplicación, y realizar\(\mathbf{v}\times \mathbf{u}\), necesitas apuntar tu dedo índice en la dirección de\(\mathbf{v}\) y tu dedo índice en la dirección de\(\mathbf{u}\) (¡todavía usando la mano derecha!). El vector resultante apuntará en la dirección opuesta (Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\)).

La magnitud de\(\mathbf{u}\times \mathbf{v}\) es el producto de las magnitudes de los vectores individuales veces\(\sin \theta\). Esta magnitud tiene una interesante interpretación geométrica: es el área del paralelogramo formado por los dos vectores (Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\)).

El producto cruzado también se puede expresar como un determinante:

\[\mathbf{u}\times \mathbf{v}= \begin{vmatrix} \hat{\mathbf{i}}&\hat{\mathbf{j}}&\hat{\mathbf{k}}\\ u_x&u_y&u_z\\ v_x&v_y&v_z\\ \end{vmatrix} \nonumber\]

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{1}\):

Dado\(\mathbf{u}=-2 \hat{\mathbf{i}}+\hat{\mathbf{j}}+\hat{\mathbf{k}}\) y\(\mathbf{v}=3 \hat{\mathbf{i}}-\hat{\mathbf{j}}+\hat{\mathbf{k}}\), calcular\(\mathbf{w}=\mathbf{u}\times \mathbf{v}\) y verificar que el resultado sea perpendicular a ambos\(\mathbf{u}\) y\(\mathbf{v}\).

Solución

\[ \begin{align*} \mathbf{u}\times \mathbf{v} &= \begin{vmatrix} \hat{\mathbf{i}}&\hat{\mathbf{j}}&\hat{\mathbf{k}}\\ u_x&u_y&u_z\\ v_x&v_y&v_z\\ \end{vmatrix}=\begin{vmatrix} \hat{\mathbf{i}}&\hat{\mathbf{j}}&\hat{\mathbf{k}}\\ -2&1&1\\ 3&-1&1\\ \end{vmatrix} \\[4pt] &=\hat{\mathbf{i}}(1+1)-\hat{\mathbf{j}}(-2-3)+\hat{\mathbf{k}}(2-3) \\[4pt] &=\displaystyle{\color{Maroon}2 \hat{\mathbf{i}}+5 \hat{\mathbf{j}}-\hat{\mathbf{k}}} \end{align*} \nonumber\]

Para verificar que dos vectores son perpendiculares realizamos el producto punto:

\[\mathbf{u} \cdot \mathbf{w}=(-2)(2)+(1)(5)+(1)(-1)=0 \nonumber\]

\[\mathbf{v} \cdot \mathbf{w}=(3)(2)+(-1)(5)+(1)(-1)=0 \nonumber\]

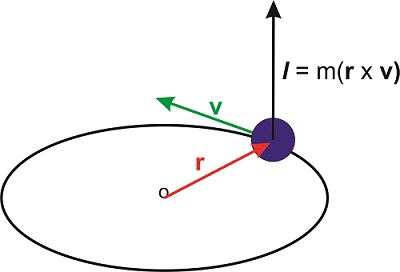

Una aplicación importante del producto cruzado implica la definición del momento angular. Si una partícula con masa\(m\) mueve una velocidad\(\mathbf{v}\) (un vector), su momento (lineal) es\(\mathbf{p}=m\mathbf{v}\). Dejar\(\mathbf{r}\) ser la posición de la partícula (otro vector), entonces el momento angular de la partícula se define como

\[\mathbf{l}=\mathbf{r}\times\mathbf{p} \nonumber\]

El momento angular es, por lo tanto, un vector perpendicular a ambos\(\mathbf{r}\) y\(\mathbf{p}\). Debido a que la posición de la partícula necesita definirse con respecto a un origen particular, este origen debe especificarse al definir el momento angular.