6.15: Cuadriláteros Inscritos en Círculos

- Page ID

- 107293

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Cuadriláteros con cada vértice en círculo y ángulos opuestos que son complementarios.

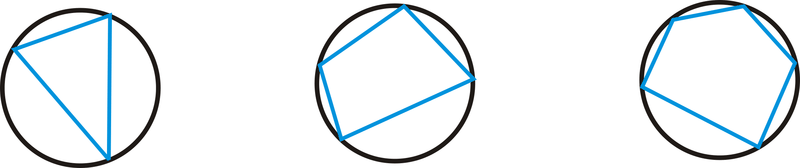

Un polígono inscrito es un polígono donde cada vértice está en el círculo, como se muestra a continuación.

Para cuadriláteros inscritos en particular, los ángulos opuestos siempre serán complementarios.

Teorema Cuadrilátero Inscrito: Un cuadrilátero se puede inscribir en círculo si y sólo si los ángulos opuestos son suplementarios.

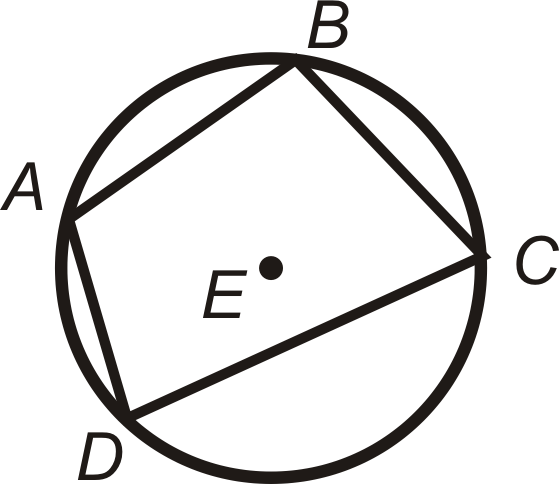

Si\(ABCD\) está inscrito en\(\bigodot E\), entonces\(m\angle A+m\angle C=180^{\circ}\) y\(m\angle B+m\angle D=180^{\circ}\). Por el contrario, Si\(m\angle A+m\angle C=180^{\circ}\) y\(m\angle B+m\angle D=180^{\circ}\), entonces\(ABCD\) se inscribe en\(\bigodot E\).

¿Y si te dieran un círculo con un cuadrilátero inscrito en él? ¿Cómo podría usar la información sobre los arcos formados por las medidas de ángulo cuadrilátero y/o cuadrilátero para encontrar la medida de los ángulos cuadriláteros desconocidos?

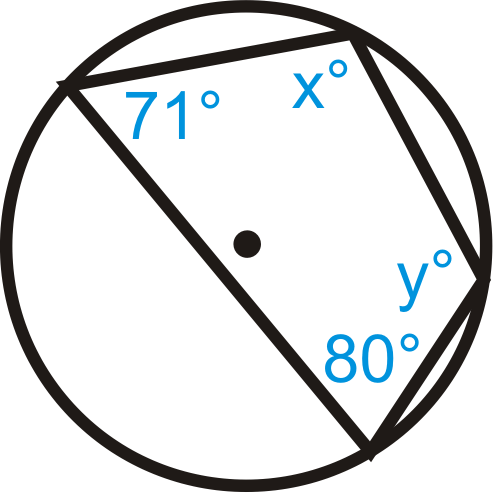

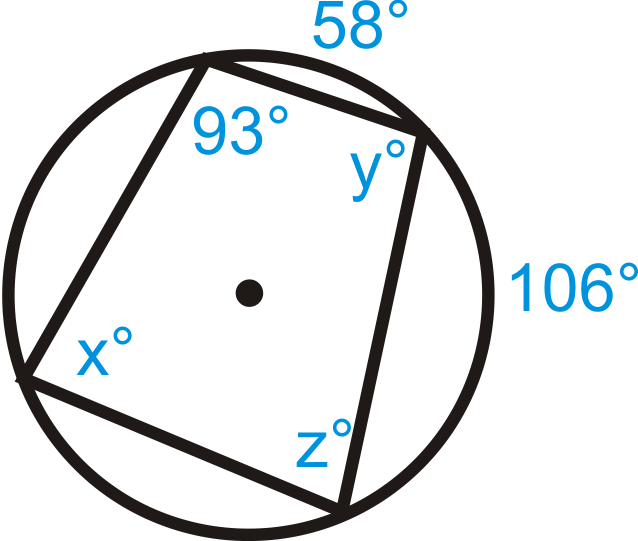

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{1}\)

-

Figura\(\PageIndex{3}\) -

Figura\(\PageIndex{4}\)

Solución

- \ (\ begin {alineado}

x+80^ {\ circ} &=180^ {\ circ}\ qquad& y+71^ {\ circ} &=180^ {\ circ}\\

x&=100^ {\ circ} & y&=109^ {\ circ}

\ end {alineado}\)

- \ (\ begin {alineado}

z+93^ {\ circ} &=180^ {\ circ} & x&=\ frac {1} {2}\ left (58^ {\ circ} +106^ {\ circ}\ derecha) & y+82^ {\ circ} &=180^ {\ circ}\\

z &=87^ {\ circ} & x &=82^ {\ circ} & y&=98^ {\ circ}

\ final {alineado}\)

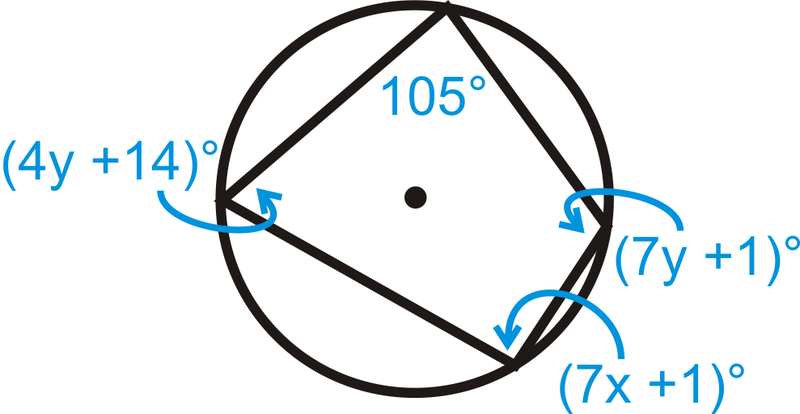

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{2}\)

Encuentra\(x\) y\(y\) en la imagen de abajo.

Solución

\ (\ begin {array} {rlrl}

(7 x+1) ^ {\ circ} +105^ {\ circ} & =180^ {\ circ} & (4 y+14) ^ {\ circ} + (7 y+1) ^ {\ circ} & =180^ {\ circ}\\

7 x+106^ {\ circ} & =180^ {\ circ} & 11 y+15^ {\ circ} & =180^ {\ circ}\\

7 x & =74 & 11 y & =165\\

x & ; =10.57 & y&=15

\ end {array}\)

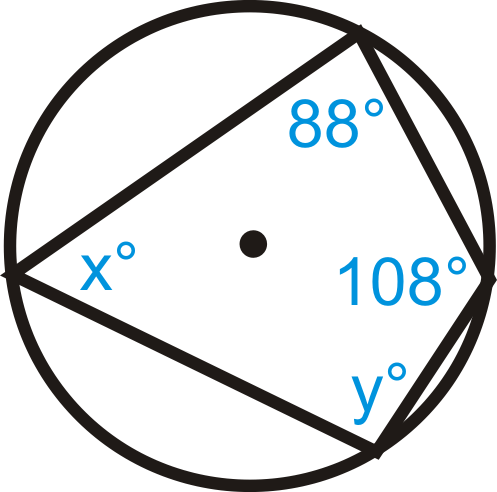

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{3}\)

Encuentra los valores de x e y en\(\bigodot A\).

Solución

Utilice el Teorema Cuadrilátero Inscrito. \(x^{\circ}+108^{\circ}=180^{\circ}\)así\(x=72^{\circ}\). Del mismo modo,\(y^{\circ}+88^{\circ}=180^{\circ}\) así\(y=92^{\circ}\).

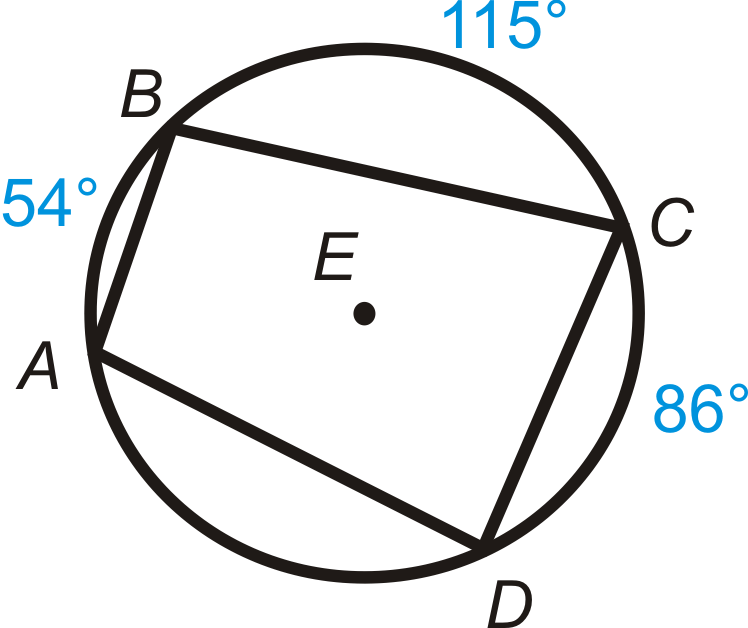

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{4}\)

Cuadrilátero\(ABCD\) está inscrito en\(\bigodot E\). Encontrar\(m\angle A\),\(m\angle B\),\(m\angle C\), y\(m\angle D\).

Solución

Primero, tenga en cuenta que\(m\widehat{AD}=105^{\circ}\) debido a que el círculo completo debe sumar hasta\(360^{\circ}\).

\(\begin{aligned}m\angle A&=\dfrac{1}{2}m\widehat{BD}=12(115+86)=100.5^{\circ} \\ m\angle B&=\dfrac{1}{2}m\widehat{AC}=12(86+105)=95.5^{\circ} \\ m\angle C&=180^{\circ}−m\angle A=180^{\circ}−100.5^{\circ}=79.5^{\circ} \\ m\angle D&=180^{\circ}−m\angle B=180^{\circ}−95.5^{\circ}=84.5^{\circ}\end{aligned}\)

Revisar

Rellene los espacios en blanco.

- Un polígono (n) _______________ tiene todos sus vértices en un círculo.

- Los ángulos _____________ de un cuadrilátero inscrito son ________________.

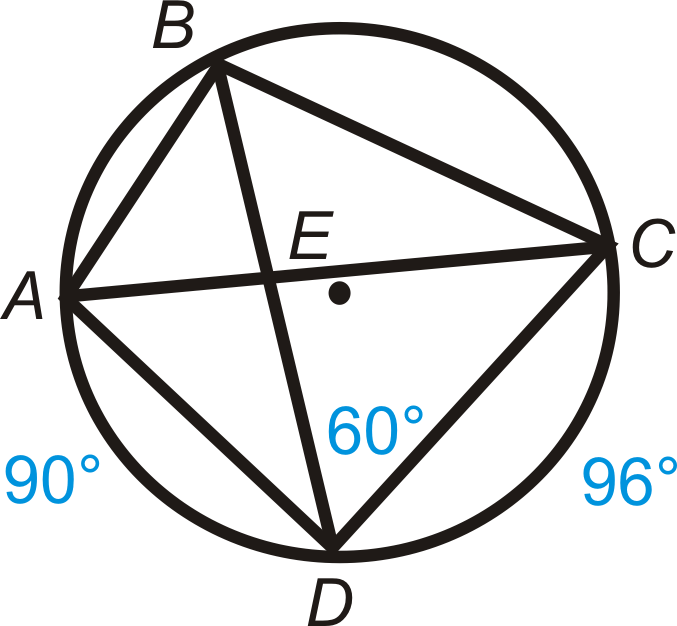

Cuadrilátero\(ABCD\) está inscrito en\(\bigodot E\). Encuentra:

- \(m\angle DBC\)

- \(m\widehat{BC}\)

- \(m\widehat{AB}\)

- \(m\angle ACD\)

- \(m\angle ADC\)

- \(m\angle ACB\)

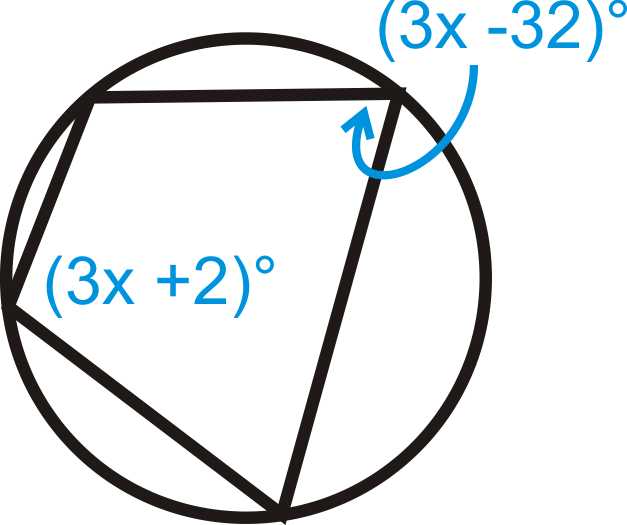

Encuentra el valor de\(x\) y/o\(y\) en\(\bigodot A\).

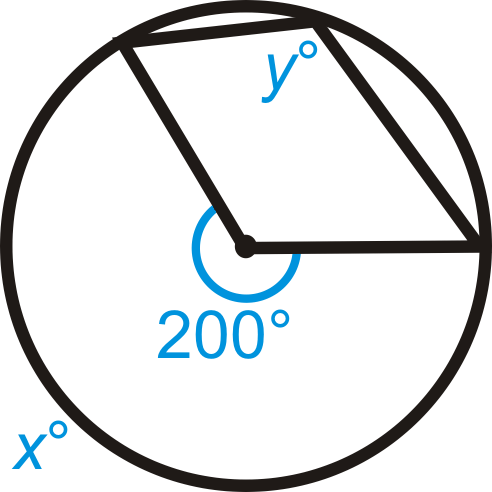

-

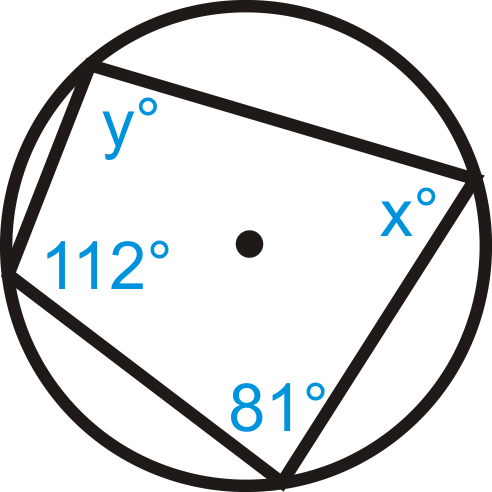

Figura\(\PageIndex{9}\) -

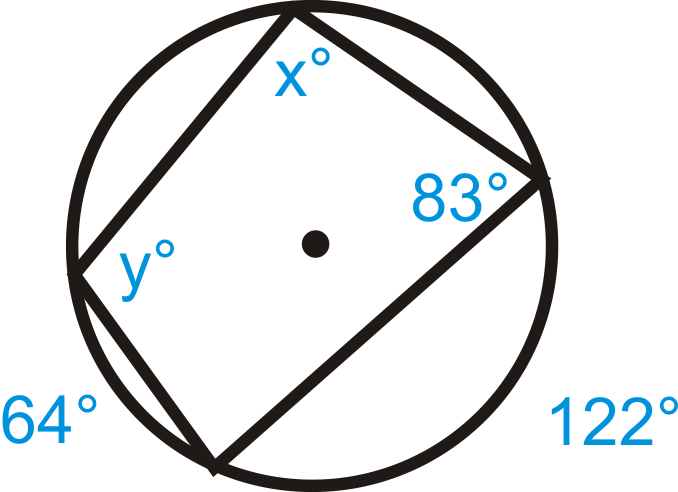

Figura\(\PageIndex{10}\) -

Figura\(\PageIndex{11}\)

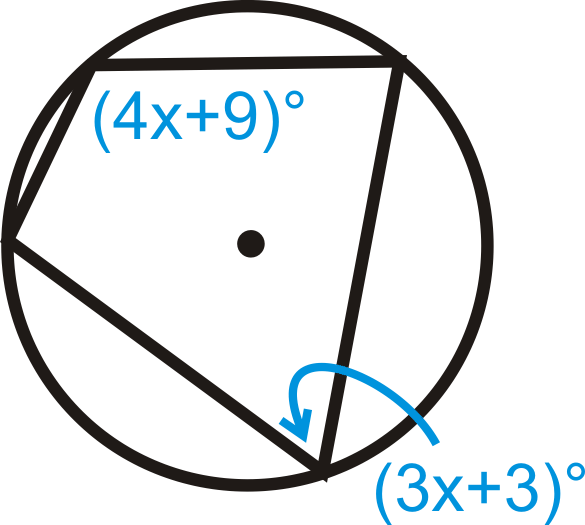

Resolver para\(x\).

-

Figura\(\PageIndex{12}\) -

Figura\(\PageIndex{13}\)

vocabulario

| Término | Definición |

|---|---|

| ángulo central | Un ángulo formado por dos radios y cuyo vértice se encuentra en el centro del círculo. |

| acorde | Un segmento de línea cuyos extremos están en un círculo. |

| círculo | El conjunto de todos los puntos que están a la misma distancia de un punto específico, llamado el centro. |

| diámetro | Un acorde que pasa por el centro del círculo. La longitud de un diámetro es dos veces la longitud de un radio. |

| ángulo inscrito | Un ángulo con su vértice en el círculo y cuyos lados son acordes. |

| arco interceptado | El arco que se encuentra dentro de un ángulo inscrito y cuyos extremos están en el ángulo. |

| radio | La distancia desde el centro hasta el borde exterior de un círculo. |

| Polígono con Inscritos | Un polígono inscrito es un polígono con cada vértice en un círculo dado. |

| Teorema Cuadrilátero con Inscritos | El Teorema Cuadrilátero Inscrito establece que un cuadrilátero puede ser inscrito en un círculo si y sólo si los ángulos opuestos del cuadrilátero son suplementarios. |

| Cuadriláteros Cíclicos | Un cuadrilátero cíclico es un cuadrilátero que se puede inscribir en un círculo. |

Recursos adicionales

Elemento Interactivo

Video: Cuadriláteros Inscritos en Círculos Principios - Básico

Actividades: Cuadriláteros Inscritos en Círculos Preguntas de Discusión

Ayudas de estudio: Guía de estudio Inscritos en Círculos

Práctica: Cuadriláteros Inscritos en Círculos

Mundo real: Amanecer en Stonehenge