3.4: Ejemplos más realistas de límites y condiciones iniciales

- Page ID

- 113776

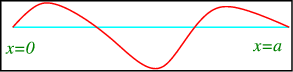

Una cadena con puntos finales fijos

Considere una cadena fija en\(x=0\) y\(x=a\), como en la Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\)

Satisface la ecuación de onda

\[\frac{1}{c^2} \frac{\partial^2 u}{\partial t^2} = \frac{\partial^2 u}{\partial x^2},\space \space\space\qquad 0<x<a, \nonumber \]

con condiciones de contorno\[u(0,t) = u(a,t) = 0, \qquad t>0, \nonumber \]

y condiciones iniciales,

\[u(x,0) = f(x), \frac{\partial u}{\partial x}(x,0) = g(x). \nonumber \]

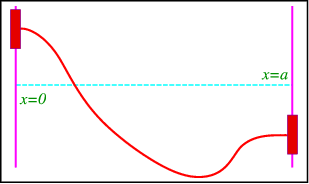

Una cadena con puntos finales libremente flotantes

Considera una cuerda con extremos sujetos a cojinetes de aire que se fijan a una varilla ortogonal al\(x\) eje. Dado que los rodamientos flotan libremente no debe haber fuerza a lo largo de las varillas, lo que significa que la cuerda es horizontal en los cojinetes (Figura\(\PageIndex{2}\)).

Satisface la ecuación de onda con las mismas condiciones iniciales que las anteriores, pero las condiciones límite ahora son\[\frac{\partial u}{\partial x} (0,t) = \frac{\partial u}{\partial x} (a,t) = 0, \space\space \qquad t>0. \nonumber \] Estas son claramente del tipo von Neumann.

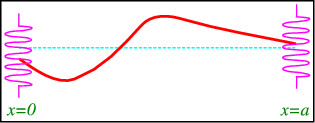

Una cadena con extremos fijos a cadenas

Para ilustrar las condiciones de contorno mixto hacemos un artilugio aún más complicado donde fijamos los extremos de la cuerda a resortes, con equilibrio en\(y=0\), ver Figura\(\PageIndex{3}\) para un boceto.

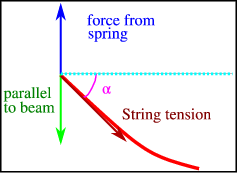

La ley de Hook establece que la fuerza ejercida por el resorte (a lo largo del\(y\) eje) es\(F=-ku(0,t)\), donde\(k\) está la constante del resorte. Esto debe ser equilibrado por la fuerza de la cuerda sobre el resorte, que es igual a la tensión\(T\) en la cuerda. El componente paralelo al\(y\) eje es\(T\sin\alpha\), donde\(\alpha\) está el ángulo con la horizontal, ver Figura\(\PageIndex{4}\).

Para pequeños\(\alpha\) tenemos

\[\sin\alpha \approx \tan\alpha = \frac{\partial u}{\partial x}(0,t). \nonumber \]

Ya que ambas fuerzas deberían cancelar encontramos

\[ {u}(0,t) -\frac{T}{k} \frac{\partial u}{\partial x}(0,t) = 0, \qquad t>0, \nonumber \]

y

\[ u(a,t) -\frac{T}{k} \frac{\partial u}{\partial x}(a,t) = 0, \nonumber \]

Se trata de condiciones de límite mixtas.