10.8: Serie Fourier-Bessel

- Page ID

- 113677

Entonces, ¿cómo podemos determinar en general los coeficientes en la serie Fourier-Bessel?

\[f(\rho) = \sum_{j=1}^\infty C_j J_\nu(\alpha_j \rho)? \nonumber \]

Se encuentra fácilmente que la versión autoadjoint correspondiente de la ecuación de Bessel es (con\(R_j(\rho) = J_\nu(\alpha_j\rho)\))

\[(\rho R_j')' + (\alpha_j^2\rho - \frac{\nu^2}{\rho}) R_j = 0. \nonumber \]

Donde asumimos eso\(f\) y\(R\) satisfacemos la condición límite

\[\begin{aligned} b_1 f(c) + b_2 f'(c) &= 0 \nonumber\\ b_1 R_j(c) + b_2 R_j'(c) & = & 0 \end{aligned} \nonumber \]

De la teoría de Sturm-Liouville sí lo sabemos\[\int_0^c \rho J_\nu(\alpha_i \rho) J_\nu(\alpha_j \rho) = 0 \;\;{\rm if\ }i \neq j, \nonumber \] pero también necesitaremos los valores cuando\(i=j\)!

Usemos la forma autoadjoint de la ecuación, y multipliquemos con\(2 \rho R'\), e integremos\(\rho\) de\(0\) a\(c\),

\[\int_0^c \left[(\rho R_j')' + (\alpha_j^2\rho - \frac{\nu^2}{\rho}) R_j \right]2 \rho R_j' d\rho = 0. \nonumber \]

Esto se puede llevar a la forma (integrar el primer término por partes, llevar los otros dos términos al lado derecho)

\[\begin{aligned} \int_0^c \frac{d}{d\rho}\left(\rho R_j'\right)^2 d\rho &= 2 \nu^2 \int_0^c R_j R_j' d\rho -2\alpha_j^2 \int_0^c \rho^2 R_j R_j' d\rho\\ \left.\left(\rho R_j'\right)^2\right|^c_0 &= \left.\nu^2 R_j^2\right|^c_0 - 2\alpha_j^2 \int_0^c \rho^2 R_j R_j' d\rho.\end{aligned} \nonumber \]

La última integral ahora se puede hacer por partes:\[\begin{aligned} 2 \int_0^c\rho^2 R_j R_j' d\rho &= -2 \int_0^c\rho R_j^2 d\rho +\left. \rho R_j^2 \right|^c_0.\end{aligned} \nonumber \]

Así que finalmente concluimos que

\[2 \alpha_j^2 \int_0^c\rho R_j^2 d\rho = \left[\left(\alpha_j^2\rho^2 - \nu^2 \right) R_j^2+\left(\rho R_j'\right)^2 \right|^c_0. \nonumber \]

Para que la vida no sea demasiado complicada solo veremos las condiciones limítrofes donde\(f(c)=R(c)=0\). ¡Los otros casos (mixtos o puramente\(f'(c)=0\)) van muy parecidos! Utilizando el hecho de que\(R_j(r) = J_\nu(\alpha_j \rho)\), encontramos\[R'_j=\alpha_j J'_\nu(\alpha_j \rho). \nonumber \] Concluimos que

\[\begin{aligned} 2 \alpha_j^2 \int_0^c\rho^2 R_j^2 d\rho &= \left[ \left(\rho \alpha_j J'_\nu(\alpha_j\rho)\right)^2 \right|^c_0 \nonumber\\ &= {c^2}\alpha_j^2 \left(J'_\nu(\alpha_j c)\right)^2 \nonumber\\ &= {c^2}\alpha_j^2 \left(\frac{\nu}{\alpha_j c} J_\nu(\alpha_j c) -J_{\nu+1}(\alpha_j c)\right)^2 \nonumber\\ &= {c^2}\alpha_j^2 \left( J_{\nu+1}(\alpha_j c)\right)^2 ,\end{aligned} \nonumber \]

Así finalmente tenemos el resultado\[\int_0^c\rho^2 R_j^2 d\rho=\frac{c^2}{2} J^2_{\nu+1}(\alpha_j c). \nonumber \]

Considera la función

\[f(x) = \left\{\begin{array}{ll} x^3 &\;\;0<x<10\\ 0&\;\;x>10 \end{array}\right. \nonumber \]

Expanda esta función en una serie de Fourier-Bessel usando\(J_3\).

Solución

De nuestras definiciones encontramos que

\[f(x) = \sum_{j=1}^\infty A_j J_3(\alpha_j x), \nonumber \]

con

\[\begin{aligned} A_j &= \frac{2}{100 J_4(10\alpha_j)^2} \int_0^{10} x^3 J_3(\alpha_j x) dx\nonumber\\ &=\frac{2}{100 J_4(10\alpha_j)^2} \frac{1}{\alpha^5_j} \int_0^{10\alpha_j} s^4 J_3(s) ds\nonumber\\ &=\frac{2}{100 J_4(10\alpha_j)^2} \frac{1}{\alpha^5_j} (10 \alpha_j)^4 J_4(10\alpha_j ) ds\nonumber\\ &= \frac{200}{\alpha_j J_4(10 \alpha_j)}.\end{aligned} \nonumber \]

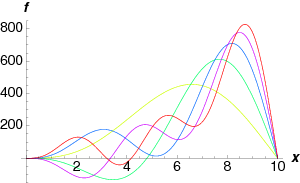

Utilizando\(\alpha_j=\ldots\), encontramos que los primeros cinco valores de\(A_j\) son\(1050.95,-821.503,703.991,-627.577,572.301\). Las primeras cinco sumas parciales se representan gráficamente en la Fig. \(\PageIndex{1}\).