9.2: Ángulo inscrito

- Page ID

- 114830

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Decimos que en el círculo se inscribe un triángulo\(\Gamma\) si se encuentran todos sus vértices\(\Gamma\).

Dejar\(\Gamma\) ser un círculo con el centro\(O\), y\(X, Y\) ser dos puntos distintos en\(\Gamma\). Entonces\(\triangle XPY\) se inscribe en\(\Gamma\) si y solo si

\[2 \cdot \measuredangle XPY \equiv \measuredangle XOY.\]

Equivalentemente, si y solo si

\(\measuredangle XPY \equiv \dfrac{1}{2} \cdot \measuredangle XOY\)o\(\measuredangle XPY \equiv \pi + \dfrac{1}{2} \cdot \measuredangle XOY.\)

- Prueba

-

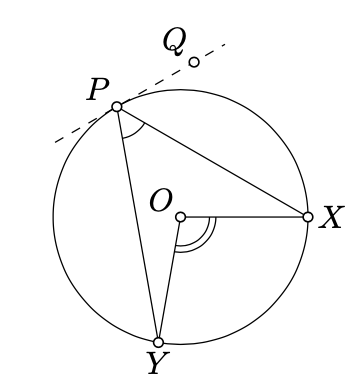

la parte “sólo si”. Dejar\((PQ)\) ser la línea tangente a\(\Gamma\) at\(P\). Por Teorema 9.1.1,

\(2 \cdot \measuredangle QPX \equiv \measuredangle POX\),\(2 \cdot \measuredangle QPY \equiv \measuredangle POY.\)

Al restar una identidad de la otra, obtenemos 9.2.1.

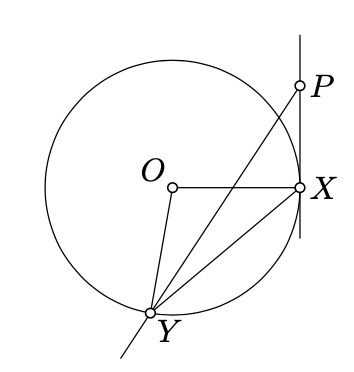

“Si” parte. Supongamos que 9.2.1 sostiene para algunos\(P \not\in \Gamma\). Tenga en cuenta que\(\measuredangle XOY \ne 0\). Por lo tanto,\(\measuredangle XPY \ne 0\) ni\(\pi\); es decir, no\(\measuredangle PXY\) es degenerado.

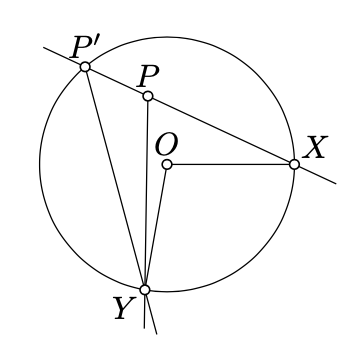

La línea\((PX)\) podría ser tangente a\(\Gamma\) en el punto\(X\) o intersecarse\(\Gamma\) en otro punto; en este último caso, supongamos que\(P'\) denota este punto de intersección.

En el primer caso, por el Teorema 9.1, tenemos

\(2 \cdot \measuredangle PXY \equiv \measuredangle XOY \equiv 2 \cdot \measuredangle XPY.\)

Aplicando la propiedad transversal (Teorema 7.3.1), obtenemos eso\((XY) \parallel (PY)\), lo cual es imposible ya que no\(\triangle PXY\) es degenerado.

En el segundo caso, aplicando la parte “si” y eso\(P, X\), y se\(P'\) encuentran en una línea (ver Ejercicio 2.4.2) obtenemos que

\(\begin{array} {rcl} {2 \cdot \measuredangle P'PY} & \equiv & {2 \cdot \measuredangle XPY \equiv \measuredangle XOY \equiv} \\ {} & \equiv & {2 \cdot \measuredangle XP'Y \equiv 2 \cdot \measuredangle XP'P.} \end{array}\)

Nuevamente, por propiedad transversal\((PY) \parallel (P'Y)\), lo cual es imposible ya que no\(\triangle PXY\) es degenerado.

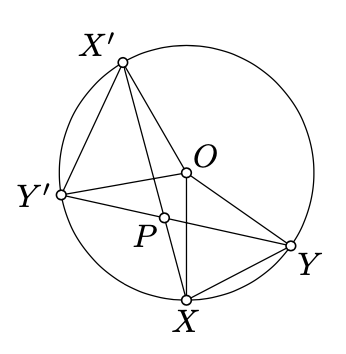

Dejar\(X, X', Y\), y\(Y'\) ser puntos distintos en el círculo\(\Gamma\). Asumir\((XX')\) se reúne\((YY')\) en un punto\(P\). Demostrar que

a)\(2 \cdot \measuredangle XPY \equiv \measuredangle XOY + \measuredangle X'OY'\);

b)\(\triangle PXY \sim \triangle PY'X'\);

(c)\(PX \cdot PX' = |OP^2 - r^2|\), donde\(O\) está el centro y\(r\) es el radio de\(\Gamma\).

(El valor\(OP^2 - r^2\) se llama la potencia del punto\(P\) con respecto al círculo\(\Gamma\). La parte (c) del ejercicio lo convierte en una herramienta útil para estudiar círculos, pero no lo vamos a considerar más en el libro.)

- Sugerencia

-

(a) Aplicar Teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\) para\(\angle XX'Y\) y\(\angle X'YY'\) y Teorema 7.4.1 para\(\triangle PYX'\).

(b) Si\(P\) está dentro de\(\Gamma\) entonces\(P\) yace entre\(X\) y\(X'\) y entre\(Y\) y y\(Y'\) en este caso\(\angle XPY\) es vertical a\(\angle X'PY'\). Si\(P\) está fuera de\(\Gamma\) entonces\([PX) = [PX')\) y\([PY) = [PY')\). En ambos casos tenemos eso\(\measuredangle XPY = \measuredangle X'PY'\).

Aplicando Teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\) y Ejercicio 2.4.2, obtenemos que

\(2 \cdot \measuredangle Y'X'P \equiv 2 \cdot \measuredangle Y'X'X \equiv 2 \cdot \measuredangle Y'YX \equiv 2 \dot \measuredangle PYX.\)

Según el Teorema 3.3.1,\(\angle Y'X'P\) y\(\angle PYX\) tienen el mismo signo; por lo tanto\(\measuredangle Y'X'P = \measuredangle PYX\). Queda por aplicar la condición de similitud AA.

(c) Aplicar (b) asumiendo\([YY']\) es el diámetro de\(\Gamma\).

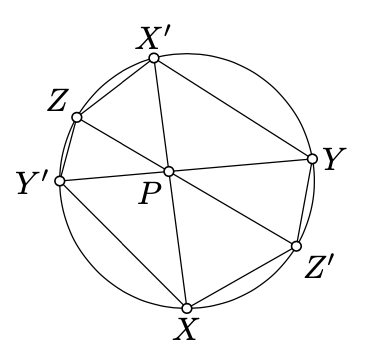

Tres acordes\([XX']\),\([YY']\), y\([ZZ']\) del círculo se\(\Gamma\) cruzan en un punto\(P\). Demostrar que

\(XY' \cdot ZX' \cdot YZ' = X'Y \cdot Z'X \cdot Y'Z.\)

- Sugerencia

-

Aplicar Exerciese\ (\ PageIndex {1} b tres veces.

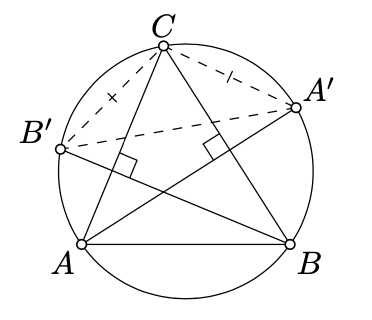

Dejar\(\Gamma\) ser un circuncírculo de un triángulo agudo\(ABC\). Dejar\(A'\) y\(B'\) denotar los segundos puntos de intersección de las altitudes desde\(A\) y\(B\) con\(\Gamma\). Demostrar que\(\triangle A'B'C\) es isósceles.

- Sugerencia

-

Dejar\(X\) y\(Y\) ser los puntos del pie de las altitudes desde\(A\) y\(B\). Supongamos que\(O\) denota el circuncentro.

Por condición AA,\(\triangle AXC \sim \triangle BYC\). Entonces

\(\measuredangle A'OC \equiv 2 \cdot \measuredangle A'AC \equiv - 2 \cdot \measuredangle B'BC \equiv - \measuredangle B'OC.\)

Por SAS,\(\triangle A'OC \cong \triangle B'OC\). Por lo tanto,\(A'C = B'C\).

Dejar\([XY]\) y\([X'Y']\) ser dos acordes paralelos de un círculo. \(XX' = YY'\)Demuéstralo.

Mira “¿Por qué está pi aquí? ¿Y por qué está cuadrado? Una respuesta geométrica al problema de Basilea” por Grant Sanderson. (Está disponible en YouTube.)

Prepara una pregunta.