15.7: Dualidad

- Page ID

- 114653

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Supongamos que se da una bijección\(P \leftrightarrow p\) entre el conjunto de líneas y el conjunto de puntos de un plano.

Configuraciones duales

Es decir, dado un punto\(P\), denotamos por\(p\) la línea correspondiente; y al revés, dada una línea\(\ell\) denotamos por\(L\) el punto correspondiente.

La biyección entre puntos y líneas se llama dualidad (La definición estándar de dualidad es más general; consideramos un caso especial que también se llama polaridad.) si

\(P\in \ell \ \ \ \Leftrightarrow \ \ \ p\ni L.\)

para cualquier punto\(P\) y línea\(\ell\).

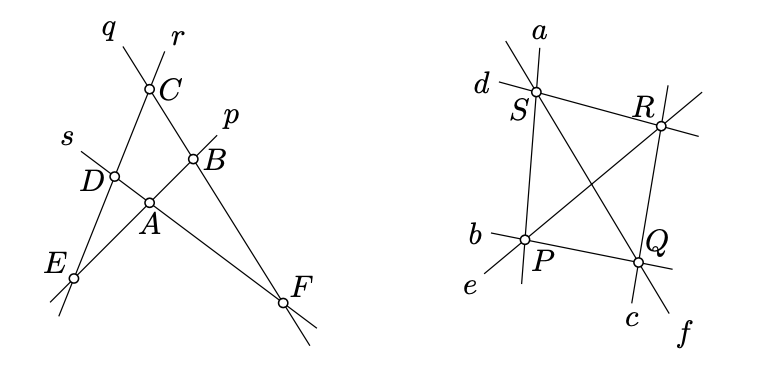

Considera la configuración de líneas y puntos en el diagrama.

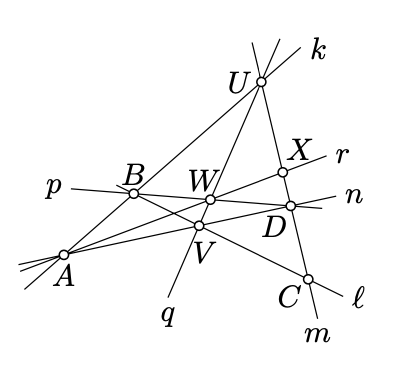

Comience con un cuadrilátero genérico\(KLMN\) y extiéndalo a un diagrama dual; etiquete las líneas y puntos usando la convención descrita anteriormente.

- Pista

-

Dibuja\(a = (KN)\)\(b = (KL)\),\(c = (LM)\),\(d = (MN)\),\(P = b \cap d\), marca y continúa.

Demostrar que el plano euclidiano no admite dualidad.

- Pista

-

Supongamos que hay una dualidad. Elija dos líneas paralelas distintas\(\ell\) y\(m\). Dejemos\(L\) y\(M\) sean sus puntos duales. \(s = (ML)\)Fijado, entonces su doble punto\(S\) tiene que estar en ambos\(\ell\) y\(m\) -una contradicción.

El plano proyectivo real admite una dualidad.

- Prueba

-

Consideremos un plano\(\Pi\) y un punto\(O \not\in \Pi\) en el espacio; supongamos que eso\(\hat{\Pi}\) denota el plano proyectivo real correspondiente.

Recordemos eso\(\Phi\) y\(\Psi\) denotan el conjunto de todas las líneas y planos que pasan a través\(O\). Según la Observación 15.3.1, existen bijecciones\(P\leftrightarrow\dot{P}\) entre puntos de\(\hat{\Pi}\) y\(\Phi\) y\(\ell \leftrightarrow \dot{\ell}\) entre líneas en\(\hat{\Pi}\) y\(\Psi\) tal que\(P\in\ell\) si y sólo si\(\dot{P} \subset \dot{\ell}\).

Queda por construir una bijección\(\dot{\ell} \leftrightarrow \dot{L}\) entre\(\Phi\) y\(\Psi\) tal que

\[\dot{P} \subset \dot{\ell} \ \ \ \iff \ \ \ \dot{p} \supset \dot{L}\]

para cualquiera de dos líneas\(\dot{P}\) y de\(\dot{L}\) paso a través\(O\).

Establecer\(\dot{\ell}\) para ser el plano a través\(O\) que es perpendicular a\(\dot{L}\). Obsérvese que ambas condiciones 15.7.1 son equivalentes a\(\dot{P} \perp \dot{L}\); de ahí el resultado sigue.

Considera el plano euclidiano con\((x,y)\) -coordenadas; supongamos que eso\(O\) denota el origen. Dado un punto\(P\ne O\) con coordenadas\((a,b)\) considera la línea\(p\) dada por la ecuación\(a\cdot x+b\cdot y=1\).

Mostrar que la correspondencia\(P\) a\(p\) se extiende a una dualidad del plano proyectivo real.

¿A qué línea corresponde\(O\)?

¿Qué punto corresponde a la línea\(a\cdot x +b\cdot y=0\)?

- Pista

-

Asumir\(M = (a, b)\) y la línea\(s\) viene dada por la ecuación\(p \cdot x + q \cdot y = 1\). Entonces\(M \in s\) es equivalente a\(p \cdot a + q \cdot b = 1\).

Este último es equivalente a\(m \ni S\) donde m es la línea dada por la ecuación\(a \cdot x+b\ cdot y = 1\) y\(S = (p, q)\).

Para extender esta bijección a todo el plano proyectivo, supongamos que (1) la línea ideal corresponde al origen y (2) el punto ideal dado por el lápiz de las líneas\(b \cdot x−a \cdot y = c\) para diferentes valores de c corresponde a la línea dada por la ecuación\(a \cdot x + b \cdot y =0\).

Dualidad dice que líneas y puntos tienen los mismos derechos en cuanto a incidencia. Permite formular una declaración dual equivalente a cualquier enunciado en geometría proyectiva. Por ejemplo, la declaración dual para “los puntos\(X\),\(Y\), y se\(Z\) encuentran en una línea\(\ell\)" serían las “líneas\(x\),\(y\), y se\(z\) cruzan en un punto \(L\)". Formulemos la declaración dual para el teorema de Desargues (Teorema 15.6.1).

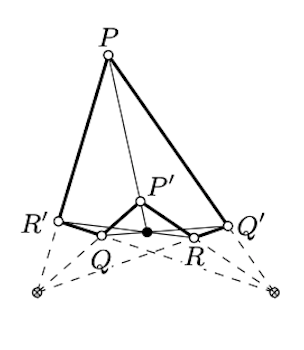

Considere los puntos colineales\(X\),\(Y\), y\(Z\). Supongamos que

Entonces las líneas\((AA')\),\((BB')\), y\((CC')\) son concurrentes.

En este teorema los puntos\(X\)\(Y\),, y\(Z\) son duales a las líneas\((AA')\)\((BB')\),, y\((CC')\) en la formulación original, y al revés.

Una vez probado el teorema de Desargues, aplicando la dualidad (Teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\)) obtenemos el teorema dual de Desargues. Nótese que el teorema dual de Desargues es lo contrario al teorema de Desargues original (Teorema 15.6.1).

Formular el teorema dual de Pappus' (ver Teorema 15.6.2).

- Pista

-

Supongamos que se da un conjunto de líneas\(a, b, c\) concurrentes y otro conjunto de líneas\(a', b', c'\) simultáneas. Set

\(\begin{array} {rclcrclcrcl} {P} & = & {b \cap c',} & \ \ \ \ & {Q} & = & {c \cap a',} & \ \ \ \ & {R} & = & {a \cap b',} \\ {P'} & = & {b' \cap c} & \ \ \ \ & {Q'} & = & {c' \cap a,} & \ \ \ \ & {R'} & = & {a' \cap b.} \end{array}\)

Entonces las líneas\((PP')\),\((QQ')\), y\((RR')\) son concurrentes. (Es un caso parcial del teorema de Brianchon.)

Resuelve el siguiente problema de construcción

- utilizando el teorema dual de Desargues;

- usando el teorema de Pappus o su dual.

- Pista

-

Asumir\((AA')\) y\((BB')\) son las líneas dadas y\(C\) es el punto dado. Aplicar el teorema de Desargues duales (Teorema\(\PageIndex{2}\) para construir de\(C'\) manera que\((AA'), (BB')\), y\((CC')\) son concurrentes. Ya que\((AA') \parallel (BB')\), lo conseguimos\((AA') \parallel (BB') \parallel (CC')\).

Ahora supongamos que\(P\) es el punto dado y\((R'Q)\),\((P'R)\) son las líneas paralelas dadas. Tratar de conformar el punto\(Q'\) como en el teorema dual de Pappus' (ver la solución de Ejercicio\(\PageIndex{4}\)).

Dadas dos líneas paralelas, construya una tercera línea paralela a través de un punto dado con una regla solamente.