19.1: Problemas clásicos

- Page ID

- 114632

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)En esta sección enumeramos un par de problemas de construcción clásica; cada uno conocido desde hace más de mil años.

Las soluciones de los siguientes dos problemas son bastante no triviales.

Construir un cuadrilátero inscrito con lados dados.

Construye un círculo que sea tangente a tres círculos dados.

Varias soluciones de este problema basadas en diferentes ideas se presentan en [9]. El siguiente ejercicio es una versión simplificada del problema de Apolonio, que sigue siendo no trivial.

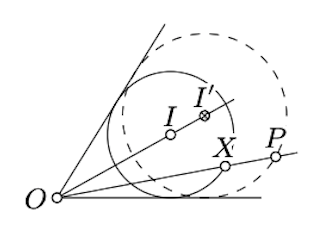

Construye un círculo que pase a través de un punto dado y sea tangente a dos líneas que se cruzan.

- Pista

-

Dejar\(O\) ser el punto de intersección de las líneas. Construye un círculo\(\Gamma\), tangente a ambas líneas, las cruces\([OP)\); denota su centro por\(I\). Supongamos que\(X\) denota uno de los puntos de intersecciones de\(\Gamma\) y\([OP)\).

Construir un punto\(I' \in [OI)\) tal que\(\dfrac{OI'}{OI} = \dfrac{OP}{OX}\). Observe que el círculo que pasa a través\(P\) y centrado en\(I'\) es una solución.

Los siguientes tres problemas no pueden resolverse en principio; es decir, no existe la necesaria construcción de brújula y regla.

Construye el lado de un nuevo cubo que tenga el volum tice tan grande como el volumen de un cubo dado.

En otras palabras, dado un segmento de la longitud\(a\), se necesita construir un segmento de longitud\(\sqrt[3]{2}\cdot a\).

Construye un cuadrado con la misma área que un círculo dado.

Si\(r\) es el radio del círculo dado, necesitamos construir un segmento de longitud\(\sqrt{\pi}\cdot r\).

De hecho, no existe una construcción de brújula y regla que trisecta el ángulo con la medida\(\dfrac{\pi}{3}\). La existencia de tal construcción implicaría la constructibilidad de un 9 gon regular que está prohibido por el siguiente resultado famoso:

Un\(n\) -gon regular inscrito en un círculo con centro\(O\) es una secuencia de puntos\(A_1\dots A_n\) en el círculo tal que

\(\measuredangle A_nOA_1=\measuredangle A_1OA_2=\dots=\measuredangle A_{n-1}OA_n=\pm\tfrac2n\cdot \pi.\)

Los puntos\(A_1,\dots, A_n\) son vértices, los segmentos\([A_1A_2], \dots, [A_nA_1]\) son lados y los segmentos restantes\([A_iA_j]\) son diagonales del\(n\) -gon.

Una construcción de un\(n\) -gon regular, por lo tanto, se reduce a la construcción de un ángulo con tamaño\(\tfrac2n\cdot \pi\).

Un\(n\) -gon regular se puede construir con una regla y una brújula si y solo si\(n\) es el producto de un poder de\(2\) y cualquier número de distintos primos Fermat.

Un primo de Fermat es un número primo de la forma\(2^k+1\) para algún número entero\(k\). Hoy en día solo se conocen cinco primos de Fermat:

3, 5, 17, 257, 65537.

Por ejemplo,

- se puede construir un gon regular de 340 ya que\(340=2^2\cdot 5\cdot 17\) y así\(5\) como\(17\) son primos Fermat;

- no se puede construir un 7-gon regular ya que no\(7\) es un primo Fermat;

- no se puede construir un 9 gon regular; altho\(9=3\cdot 3\) es un producto de dos primos Fermat, estos primos no son distintos.

La imposibilidad de estas construcciones se demostró sólo en el siglo XIX. El método utilizado en las pruebas se indica en la siguiente sección.