20.1: Triángulos sólidos

- Page ID

- 114499

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

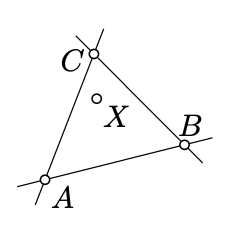

Decimos que el punto\(X\) se encuentra dentro de un triángulo no degenerado\(ABC\) si se mantienen las siguientes tres condiciones:

- \(A\)y\(X\) se encuentran en el mismo lado de la línea\((BC)\);

- \(B\)y\(X\) se encuentran en el mismo lado de la línea\((CA)\);

- \(C\)y\(X\) se encuentran en el mismo lado de la línea\((AB)\).

El conjunto de todos los puntos dentro\(\triangle ABC\) y en sus lados\([AB]\),\([BC]\), se\([CA]\) denominará triángulo sólido\(ABC\) y se denotará por\(\blacktriangle ABC\).

Mostrar que cualquier triángulo sólido es convexo; es decir, para cualquier par de puntos\(X,Y\in\blacktriangle ABC\), entonces el segmento de línea\([XY]\) se encuentra en\(\blacktriangle ABC\).

- Pista

-

Asumir lo contrario; es decir, hay un punto\(W \in [XY]\) tal que\(W \not\in \blacktriangle ABC\).

Sin pérdida de generalidad, podemos suponer que W y A se encuentran en los lados opuestos de la línea\((BC)\).

Implemente que ambos segmentos\([W X]\) y se\([W Y]\) crucen\((BC)\). Por Axioma II,\(W \in (BC)\) — una contradicción.

Las notaciones\(\triangle ABC\) y\(\blacktriangle ABC\) se ven similares, también tienen significados cercanos pero diferentes, que mejor no confundir. Recordemos que\(\triangle ABC\) es un triple ordenado de puntos distintos (ver página), mientras que\(\blacktriangle ABC\) es un conjunto infinito de puntos.

En particular,\(\blacktriangle ABC=\blacktriangle BAC\) para cualquier triángulo\(ABC\). En efecto, cualquier punto que pertenezca al conjunto\(\blacktriangle ABC\) también pertenece al conjunto\(\blacktriangle BAC\) y al revés. Por otro lado,\(\triangle ABC \ne \triangle BAC\) simplemente porque el triple ordenado de puntos\((A,B,C)\) es distinto del triple ordenado\((B,A,C)\).

Tenga en cuenta que\(\blacktriangle ABC\cong\blacktriangle BAC\) aunque\(\triangle ABC\ncong\triangle BAC\), donde congruencia de los conjuntos\(\blacktriangle ABC\) y\(\blacktriangle BAC\) se entiende de la siguiente manera:

Dos conjuntos\(\mathcal{S}\) y\(\mathcal{T}\) en el plano se llaman congruentes (brevemente\(\mathcal{S}\cong \mathcal{T}\)) si\(\mathcal{T}=f(\mathcal{S})\) por algún movimiento\(f\) del plano.

Si no\(\triangle ABC\) es degenerado y

\(\blacktriangle ABC\cong \blacktriangle A'B'C',\)

luego después de volver a etiquetar los vértices de\(\triangle ABC\) tendremos

\(\triangle ABC\cong \triangle A'B'C'.\)

En efecto, basta con mostrar que si\(f\) es un movimiento\(\blacktriangle ABC\) al que se mapea\(\blacktriangle A'B'C'\), entonces\(f\) mapea cada vértice de\(\triangle ABC\) a un vértice\(\triangle A'B'C'\). Esto último se desprende de la caracterización de vértices de triángulos sólidos dada en el siguiente ejercicio:

Que no\(\triangle ABC\) se degenere y\(X\in \blacktriangle ABC\). Mostrar que\(X\) es un vértice de\(\triangle ABC\) si y sólo si hay una línea\(\ell\) que se cruza\(\blacktriangle ABC\) en el único punto\(X\).

- Pista

-

Para probar la parte “sólo si”, considera la línea que pasa por el vértice que es paralela al lado opuesto.

Para probar la parte “si”, utilice el teorema de Pasch (Teorema 3.4.1).