20.2: Conjuntos poligonales

- Page ID

- 114491

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)El conjunto elemental en el plano es un conjunto de uno de los siguientes tres tipos:

- conjunto de un punto;

- segmento;

- triángulo sólido.

Un conjunto en el plano se llama poligonal si se puede presentar como una unión de una colección finita de conjuntos elementales.

Tenga en cuenta que de acuerdo con esta definición, el conjunto vacío\(\emptyset\) es un conjunto poligonal. En efecto,\(\emptyset\) es una unión de una colección vacía de conjuntos elementales.

Un conjunto poligonal se llama degenerado si se puede presentar como unión de número finito de conjuntos de un punto y segmentos.

Si\(X\) y\(Y\) se encuentran en lados opuestos de la línea\((AB)\), entonces la unión\(\blacktriangle AXB\cup \blacktriangle BYA\) es un conjunto poligonal que se llama cuadrilátero sólido\(AXBY\) y denotado por\(\blacksquare AXBY\). En particular, podemos hablar de paralelogramos sólidos, rectángulos y cuadrados.

Por lo general, un conjunto poligonal admite muchas presentaciones como una unión de una colección finita de conjuntos elementales. Por ejemplo, si\(\square AXBY\) es un paralelogramo, entonces

\(\blacksquare AXBY=\blacktriangle AXB\cup \blacktriangle AYB=\blacktriangle XAY\cup \blacktriangle XBY.\)

Demostrar que un cuadrado sólido no es degenerado.

- Sugerencia

-

Supongamos lo contrario: es decir, un cuadrado sólido\(\mathcal{Q}\) puede presentarse como una unión de una colección finita de segmentos\([A_1B_1], \dots, [A_nB_n]\) y conjuntos de un punto\(\{C_1\}, \dots, \{C_k\}\).

Tenga en cuenta que\(\mathcal{Q}\) contiene un número infinito de segmentos mutuamente no paralelos. Por lo tanto, podemos elegir un segmento\([PQ]\) en\(\mathcal{Q}\) que no sea paralelo a ninguno de los segmentos\([A_1B_1], \dots, [A_nB_n]\).

De ello se deduce que\([PQ]\) tiene a lo sumo un punto común con cada uno de los conjuntos\([A_iB_i]\) y\(\{C_i\}\). Ya que\([PQ]\) contiene número infinito de puntos, llegamos a una contradicción.

Mostrar que un círculo no es un conjunto poligonal.

- Sugerencia

-

Primero tenga en cuenta que entre los conjuntos elementales solo los conjuntos de un punto pueden ser subconjuntos del círculo a. Queda por señalar que cualquier círculo contiene un número infinito de puntos.

Para cualquiera de dos conjuntos poligonales\(\mathcal{P}\) y\(\mathcal{Q}\), la unión así\(\mathcal{P}\cup\mathcal{Q}\) como la intersección también\(\mathcal{P} \cap \mathcal{Q}\) son conjuntos poligonales.

- Prueba

-

Presentemos\(\mathcal{P}\) y\(\mathcal{Q}\) como una unión de colección finita de conjuntos elementales\(\mathcal{P}_1,\dots,\mathcal{P}_k\) y\(\mathcal{Q}_1,\dots,\mathcal{Q}_n\) respectivamente.

Tenga en cuenta que

\(\mathcal{P}\cup\mathcal{Q} = \mathcal{P}_1 \cup \dots \cup \mathcal{P}_k \cup \mathcal{Q}_1 \cup \dots \cup \mathcal{Q}_n.\)

Por lo tanto,\(\mathcal{P}\cup\mathcal{Q}\) es poligonal.

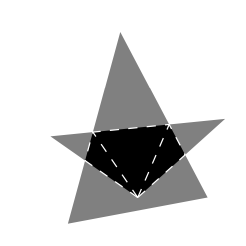

Tenga en cuenta que\(\mathcal{P}\cap \mathcal{Q}\) es la unión de conjuntos\(\mathcal{P}_i\cap \mathcal{Q}_j\) para todos\(i\) y\(j\). Por lo tanto, para mostrar que\(\mathcal{P}\cap \mathcal{Q}\) es poligonal, basta con mostrar que cada uno\(\mathcal{P}_i\cap \mathcal{Q}_j\) es poligonal para cualquier par\(i\),\(j\).

El diagrama debe sugerir una idea para la prueba de esta última afirmación en caso\(\mathcal{P}_i\) de\(\mathcal{Q}_j\) que sean triángulos sólidos. Los otros casos son más simples; se puede construir una prueba formal sobre el Ejercicio 20.1.1.

Una clase de conjuntos que está cerrada con respecto a la unión y la intersección se denomina anillo de conjuntos. El reclamo anterior, por lo tanto, establece que los conjuntos poligonales en el plano forman un anillo de conjuntos.