4.7: TMS VIII #1

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

1 La superficie10′. El 4to del ancho al ancho me he unido, a 3 he ido... sobre

2 la longitud5′ fue más allá. Tú, 4, del cuarto, tanto como el ancho postular. El cuarto de 4 toma, 1 ya ves.

3 1 a 3 van, 3 ves. 4 cuartas partes del ancho a 3 se unen, 7 ves.

4 7 tanto como postulación de longitud. 5′el ir más allá a lo que va a ser arrancado de la posición de longitud. 7, de la longitud, a 4, ¿de la anchura? , elevar,

5 28 ves. 28, de las superficies, a10′ la superficie elevarse,4∘40′ ya ves.

65′, el que va a ser arrancado de la longitud, a cuatro, del ancho, subir,20′ ya ves. 12romper,10′ ya ves. 10′hacer bodega,

71′40′′ ya ves. 1′40′′para4∘40′ unirse,4∘41′40′′ ya ves. ¿Qué es igual? 2∘10′ya ves.

810′ ¿...? para2∘10′ unirse,2∘20′ ya ves. Qué al 28, de las superficies, ¿puedo postular cuál me2∘10′ da?

95′ postular. 5′a 7 subir,35′ ya ves. 5′, el que va a ser arrancado de la longitud, de35′ arrancar,

1030′ ya ves,30′ la longitud. 5′la longitud a 4 del ancho subir,20′ ya ves, 20 el largo (error por ancho).

En BM 13901 #12 vimos cómo un problema sobre los cuadrados podría reducirse a un problema de rectángulo. Aquí, por el contrario, un problema sobre un rectángulo se reduce a un problema sobre cuadrados.

Traducido a símbolos, el problema es el siguiente;

74w−ℓ=5′, (ℓ,w)=10′

(ℓ,w)=10′

(“a 3 he ido” en la línea 1 significa que la “unión” de14w en la línea 1 se repite tres veces). El problema podría haberse resuelto de acuerdo con los métodos utilizados en TMS IX #3 (página 57), es decir, de la siguiente manera:

7w−4ℓ=4⋅5′, (ℓ,w)=10′

(ℓ,w)=10′

7w−4ℓ=20′, (7w,4ℓ)=(7⋅4)⋅10′=28⋅10′=4∘40′

(7w,4ℓ)=(7⋅4)⋅10′=28⋅10′=4∘40′

7w=√4∘40′+(20′2)2+20′2=2∘20,

\ (\ begin {array} {l}

4\ ell=\ sqrt {4^ {\ circ} 40^ {\ prime} +\ left (\ frac {20^ {\ prime}} {2}\ derecha) ^ {2}} -\ frac {20^ {\ prime}} {2} =2\

w=20^ {\ prime},\ quad\ ell=30^ {prime}

\ end {array}\).

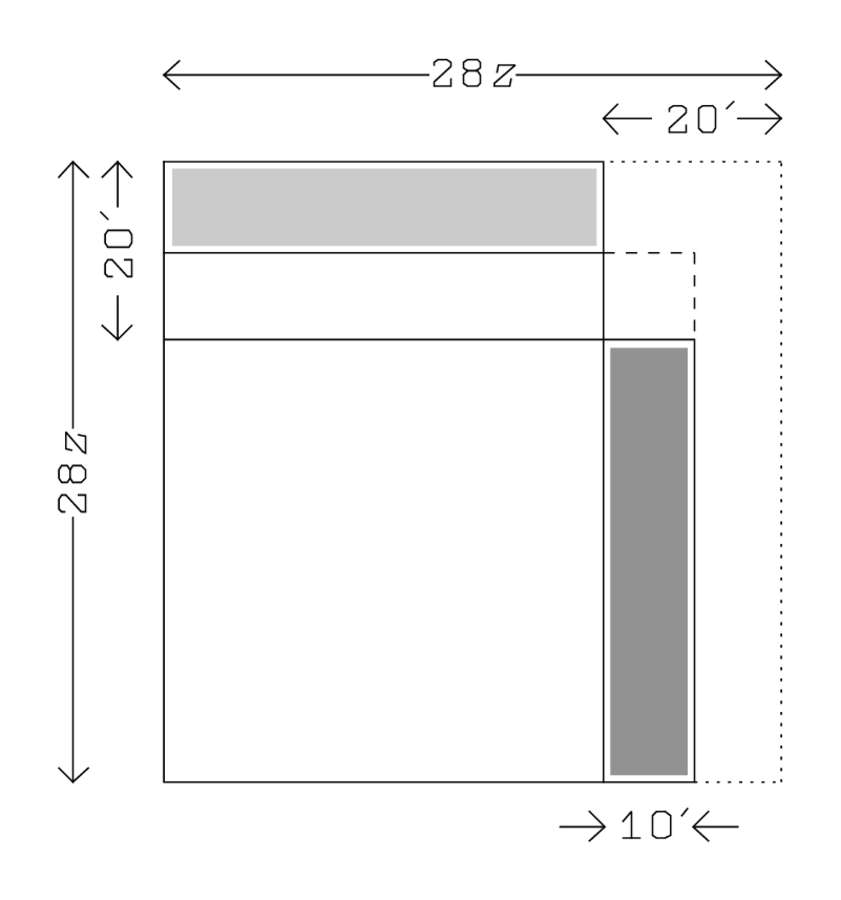

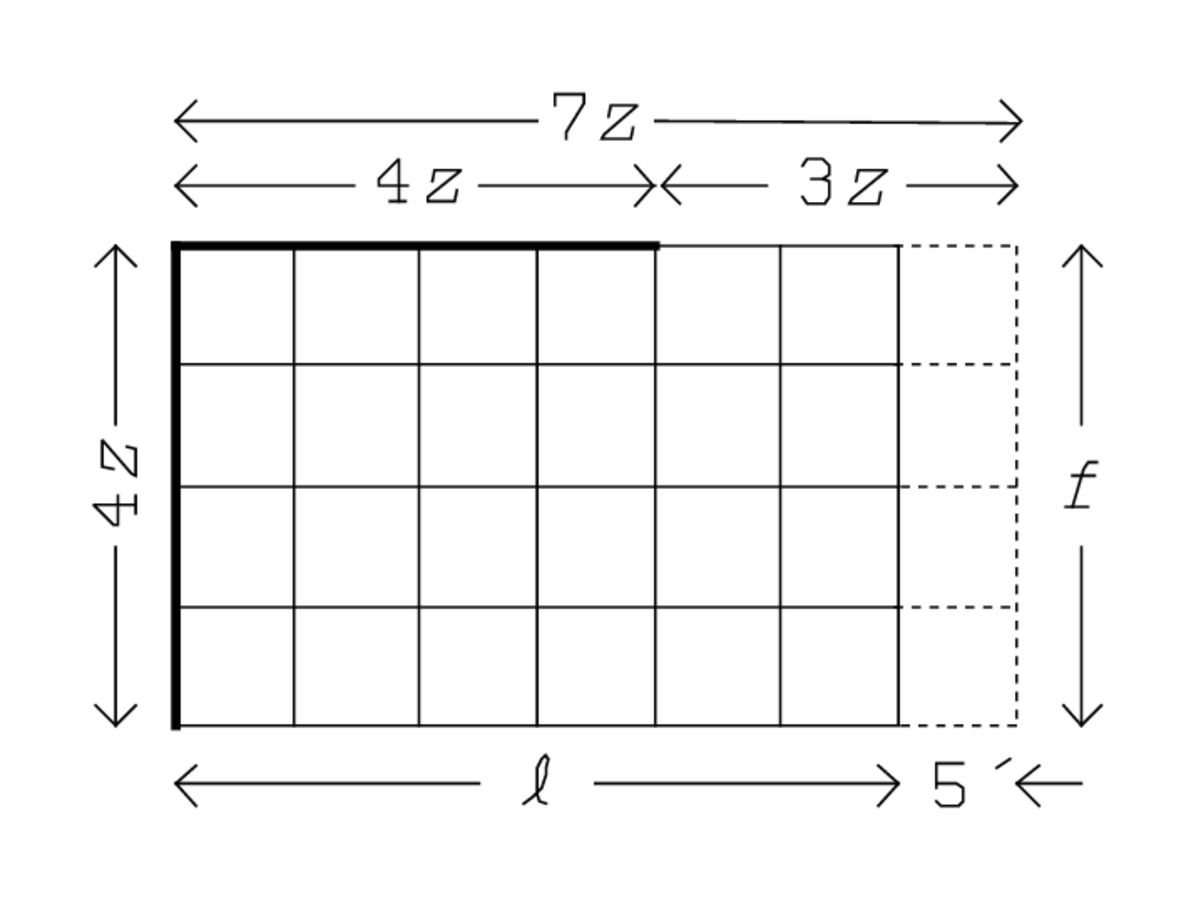

No obstante, una vez más la calculadora muestra que tiene varias cuerdas en su arco, y que puede elegir entre ellas como le parezca conveniente. Aquí construye su aproximación sobre un cuadrado cuyo lado(z) es14 del ancho (Figura 4.13). De esa manera, la anchura será igual a 4, entendida como 4z (Tú, 4, del cuarto, tanto como la anchura postular), y la longitud prolongada por5′ será igual a 7, entendida como7z (7 en la medida de lo posible). La línea 4 encuentra que el rectángulo con lados7z y4z —en otras palabras, el rectángulo inicial prolongado por5′ —consiste en7⋅4=28 pequeños cuadrados◻(z). 11 Estas 28 plazas rebasan el área10′ por cierto número de lados (n⋅z), cuya determinación se aplaza hasta más tarde. Como de costumbre, de hecho, el problema no normalizado

28◻(z)−n⋅z=10′

se transforma en

◻(28z)−n⋅(28z)=28⋅10′=4∘40′.

La línea 6 encuentran=4⋅5′=20′, y de aquí en adelante todo sigue la rutina, como puede verse en la Figura 4.14: 28z será igual a2∘20, yz por lo tanto a5′. 12 Por lo tanto, la longitudℓ será7⋅5′−5′=30′, y la anchuraw4⋅5′=20′.