1.18: Adhesión en Diatómica

- Page ID

- 69883

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

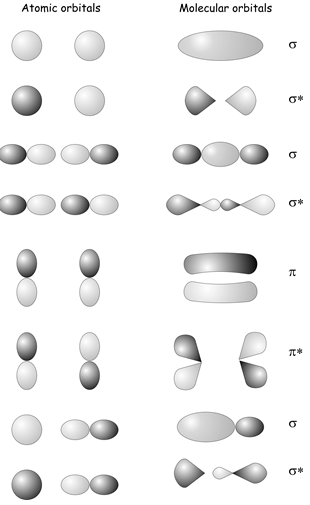

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\) Ya estarás familiarizado con la idea de construir orbitales moleculares a partir de combinaciones lineales de orbitales atómicos de cursos anteriores que cubren la unión en moléculas diatómicas. Al considerar las simetrías de\(s\) and \(p\) orbitals on two atoms, we can form bonding and antibonding combinations labeled as having either \(\sigma\) o\(\pi\) simetría dependiendo de si se asemejan\(s\) or \(p\) orbitals when viewed along the bond axis (see diagram below). In all of the cases shown, only atomic orbitals that have the same symmetry when viewed along the bond eje\(z\) can form a chemical bond e.g. two \(s\) orbitals, two \(p_z\) orbitals , or an \(s\) and a \(p_z\) can form a bond, but a \(p_z\) and a \(p_x\) or an \(s\) and a \(p_x\) or a \(p_y\) cannot. It turns out that the rule that determines whether or not two atomic orbitals can bond is that they must belong to the same symmetry species within the point group of the molecule.

Ya estarás familiarizado con la idea de construir orbitales moleculares a partir de combinaciones lineales de orbitales atómicos de cursos anteriores que cubren la unión en moléculas diatómicas. Al considerar las simetrías de\(s\) and \(p\) orbitals on two atoms, we can form bonding and antibonding combinations labeled as having either \(\sigma\) o\(\pi\) simetría dependiendo de si se asemejan\(s\) or \(p\) orbitals when viewed along the bond axis (see diagram below). In all of the cases shown, only atomic orbitals that have the same symmetry when viewed along the bond eje\(z\) can form a chemical bond e.g. two \(s\) orbitals, two \(p_z\) orbitals , or an \(s\) and a \(p_z\) can form a bond, but a \(p_z\) and a \(p_x\) or an \(s\) and a \(p_x\) or a \(p_y\) cannot. It turns out that the rule that determines whether or not two atomic orbitals can bond is that they must belong to the same symmetry species within the point group of the molecule.

Podemos demostrarlo matemáticamente para dos orbitales atómicos\(\phi_i\) y\(\phi_j\) observando la integral de superposición entre los dos orbitales.

\[S_{ij} = \langle \phi_i|\phi_j \rangle = \int \phi_i^* \phi_j d\tau \: \: \: \: \: \: \: \: \: \: \: \: \: \: \: \: \text(18.1)\]

Para que la unión sea posible, esta integral debe ser distinta de cero. El producto de las dos funciones\(\phi_1\) y\(\phi_2\) se transforma como el producto directo de sus especies de simetría es decir\(\Gamma_{12}\) =\(\Gamma_1 \otimes \Gamma_2\). Como se explicó anteriormente, para que la integral de superposición sea distinta de cero,\(\Gamma_{12}\) debe contener la representación irreducible totalmente simétrica (\(A_{1g}\) for a homonuclear diatomic, which belongs to the point group \(D_{\infty h}\)). As it happens, this is only possible if \(\phi_1\)y\(\phi_2\) pertenecer a la misma irreducible representación. Estas ideas se resumen para una diatómica en la siguiente tabla.

\[\begin{array}{lllll} \hline \text{First Atomic Orbital} & \text{Second Atomic Orbital} & \Gamma_1 \otimes \Gamma_2 & \text{Overlap Integral} & \text{Bonding?} \\ \hline s \: (A_{1g}) & s \: (A_{1g}) & A_{1g} & \text{Non-zero} & \text{Yes} \\ s \: (A_{1g}) & p_x \: (E_{1u}) & E_{1u} & \text{Zero} & \text{No} \\ s \: (A_{1g}) & p_z \: (A_{1u}) & A_{1u} & \text{Zero} & \text{No} \\ p_x \: (E_{1u}) & p_x \: (E_{1u}) & A_{1g} + A_{2g} + E_{2g} & \text{Non-zero} & \text{Yes} \\ p_X \: (E_{1u}) & p_z \: (A_{1u}) & E_{1g} & \text{Zero} & \text{No} \\ p_z \: (A_{1u}) & p_z \: (A_{1u}) & A_{1g} & \text{Non-zero} & \text{Yes} \end{array} \tag{18.2}\]