5.6: Multiplicar polinomios

- Page ID

- 111703

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)En esta sección encontraremos los productos de expresiones y funciones polinómicas. Comenzamos con el producto de dos monomios, luego egresamos al producto de un monomio y polinomio, y completamos el estudio encontrando el producto de cualquiera de dos polinomios.

El Producto de los Monomios

Mientras todas las operaciones sean multiplicadoras, podemos usar las propiedades conmutativas y asociativas para cambiar el orden y reagruparnos.

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{1}\)

Multiplicar:\(−5(7y)\). Simplificar:\(−5(7y)\).

Solución

Utilice las propiedades conmutativas y asociativas para cambiar el orden y reagruparse.

\[\begin{align*} -5(7 y) &= [(-5)(7)] y \quad &\color {Red} \text { Reorder. Regroup. } \\ &= -35 y \quad &\color {Red} \text { Multiply: } (-5)(7)=-35 \end{align*} \nonumber \]

Ejercicio\(\PageIndex{1}\)

Multiplicar:\(3(4 x)\)

- Contestar

-

\(12x\)

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{2}\)

Multiplicar:\((−3x^2)(4x^3)\). Simplificar:\((−3x^2)(4x^3)\).

Solución

Utilice las propiedades conmutativas y asociativas para cambiar el orden y reagruparse.

\[\begin{aligned} \left(-3 x^{2}\right)\left(4 x^{3}\right) &= [(-3)(4)]\left(x^{2} x^{3}\right) \quad \color {Red} \text { Reorder. Regroup. } \\ &= -12 x^{5} \quad \color {Red} \text { Multiply: }(-3)(4)=12, x^{2} x^{3}=x^{5}\end{aligned} \nonumber\]

Ejercicio\(\PageIndex{2}\)

Multiplicar:\((7 y^5)(−2y^2)\)

- Contestar

-

\(-14 y^{7}\)

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{3}\)

Multiplicar:\((−2a^2b^3)(−5a^3b)\). Simplificar:\((−2a^2b^3)(−5a^3b)\).

Solución

Utilice las propiedades conmutativas y asociativas para cambiar el orden y reagruparse.

\[\begin{aligned} \left(-2 a^{2} b^{3}\right)\left(-5 a^{3} b\right) &=[(-2)(-5)]\left(a^{2} a^{3}\right)\left(b^{3} b\right) \quad \color {Red} \text { Reorder. Regroup. } \\ &=10 a^{5} b^{4} \quad \color {Red} \text { Multiply: }(-2)(-5)=10, a^{2} a^{3}=a^{5}, \text { and } b^{3} b=b^{4}\end{aligned} \nonumber\]

Ejercicio\(\PageIndex{3}\)

Multiplicar:\(( −6st^2)(3s^3t^4)\)

- Contestar

-

\(-18 s^{4} t^{6}\)

Al multiplicar los monomios, es mucho más eficiente hacer mentalmente los cálculos requeridos. En el caso del Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{1}\), multiplicar\(−5\) y\(7\) mentalmente para obtener\[−5(7y)=−35y \nonumber \] En el caso del Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{2}\),\(4\) multiplicar\(−3\) y obtener\(−12\), después repetir la base\(x\) y sumar exponentes para obtener\[(−3x^2)(4x^3)=−12x^5 \nonumber \] Finalmente, en el caso del Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{3}\), \(−5\)multiplicar\(−2\) y obtener\(10\), luego repetir las bases y sumar sus exponentes. \[(−2a^2b^3)(−5a^3b) = 10 a^5b^4 \nonumber \]

Multiplicando un Monomio y un Polinomio

Ahora volvemos nuestra atención al producto de un monomio y un polinomio.

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{4}\)

Multiplicar:\(5\left(3 x^{2}-4 x-8\right)\)

Solución

Primero tenemos que distribuir los\(5\) tiempos de cada término del polinomio. Entonces multiplicamos mentalmente los monomios resultantes.

\[\begin{aligned} 5\left(3 x^{2}-4 x-8\right) &=5\left(3 x^{2}\right)-5(4 x)-5(8) \\ &=15 x^{2}-20 x-40 \end{aligned} \nonumber \]

Ejercicio\(\PageIndex{4}\)

Multiplicar:\(4\left(-2 y^{2}+3 y+5\right)\)

- Contestar

-

\(-8 y^{2}+12 y+20\)

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{5}\)

Multiplicar:\(2 y(-3 y+5) \)

Solución

Primero tenemos que distribuir los\(2y\) tiempos de cada término del polinomio. Entonces multiplicamos mentalmente los monomios resultantes.

\[\begin{aligned} 2 y(-3 y+5) &=2 y(-3 y)+2 y(5) \\ &=-6 y^{2}+10 y \end{aligned} \nonumber \]

Ejercicio\(\PageIndex{5}\)

Multiplicar:\(-3 x(4-2 x)\)

- Contestar

-

\(-12 x+6 x^{2}\)

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{6}\)

Multiplicar:\(-3 a b\left(a^{2}+2 a b-b^{2}\right)\)

Solución

Primero tenemos que distribuir los\(−3ab\) tiempos de cada término del polinomio. Entonces multiplicamos mentalmente los monomios resultantes.

\[\begin{aligned}-3 a b\left(a^{2}+2 a b-b^{2}\right) &=-3 a b\left(a^{2}\right)+(-3 a b)(2 a b)-(-3 a b)\left(b^{2}\right) \\ &=-3 a^{3} b+\left(-6 a^{2} b^{2}\right)-\left(-3 a b^{3}\right) \\ &=-3 a^{3} b-6 a^{2} b^{2}+3 a b^{3} \end{aligned} \nonumber \]

Solución alternativa:

Es mucho más eficiente realizar la mayoría de los pasos del producto\(−3ab(a^2 +2ab−b^2)\) mentalmente. Sabemos que debemos\(−3ab\) multiplicar por cada uno de los términos del polinomio\(a^2 +2ab−b^2\). Aquí están nuestros cálculos mentales:

- \(−3ab\)veces\(a^2\) es igual\(−3a3b\).

- \(−3ab\)veces\(2ab\) es igual\(−6a^2b^2\).

- \(−3ab\)veces\(−b^2\) es igual\(3ab^3\).

Pensar de esta manera nos permite anotar la respuesta sin ninguno de los pasos mostrados en nuestra primera solución. Es decir, inmediatamente escribimos:

\[-3 a b\left(a^{2}+2 a b-b^{2}\right)=-3 a^{3} b-6 a^{2} b^{2}+3 a b^{3} \nonumber \]

Ejercicio\(\PageIndex{6}\)

Multiplicar:\(2 x y\left(x^{2}-4 x y^{2}+7 x\right)\)

- Contestar

-

\(2 x^{3} y-8 x^{2} y^{3}+14 x^{2} y\)

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{7}\)

Multiplicar:\(-2 z^{2}\left(z^{3}+4 z^{2}-11\right)\)

Solución

Primero tenemos que distribuir los\(−2z^2\) tiempos de cada término del polinomio. Entonces multiplicamos mentalmente los monomios resultantes.

\[\begin{aligned}-2 z^{2}\left(z^{3}+4 z^{2}-11\right) &=-2 z^{2}\left(z^{3}\right)+\left(-2 z^{2}\right)\left(4 z^{2}\right)-\left(-2 z^{2}\right)(11) \\ &=-2 z^{5}+\left(-8 z^{4}\right)-\left(-22 z^{2}\right) \\ &=-2 z^{5}-8 z^{4}+22 z^{2} \end{aligned} \nonumber \]

Solución alternativa:

Es mucho más eficiente realizar la mayoría de los pasos del producto\(−2z^2(z^3 +4z^2 −11)\) mentalmente. Sabemos que debemos\(−2z^2\) multiplicar por cada uno de los términos del polinomio\(z^3 +4z^2 −11\). Aquí están nuestros cálculos mentales:

- \(−2z^2\)veces\(z^3\) es igual\(−2z^5\).

- \(−2z^2\)veces\(4z^2\) es igual\(−8z^4\).

- \(−2z^2\)veces\(−11\) es igual\(22z^2\).

Pensar de esta manera nos permite anotar la respuesta sin ninguno de los pasos mostrados en nuestra primera solución. Es decir, inmediatamente escribimos:

\[-2 z^{2}\left(z^{3}+4 z^{2}-11\right)=-2 z^{5}-8 z^{4}+22 z^{2} \nonumber \]

Ejercicio\(\PageIndex{7}\)

Multiplicar:\(-5 y^{3}\left(y^{2}-2 y+1\right)\)

- Contestar

-

\(-5 y^{5}+10 y^{4}-5 y^{3}\)

Multiplicar polinomios

Ahora que hemos aprendido a tomar el producto de dos monomios o el producto de un monomio y un polinomio, podemos aplicar lo que hemos aprendido para multiplicar dos polinomios arbitrarios.

Antes de comenzar con los ejemplos, volvamos a visitar la propiedad distributiva. Sabemos que\[2 \cdot(3+4)=2 \cdot 3+2 \cdot 4 \nonumber \] Ambas partes son iguales a\(14\). Estamos acostumbrados a tener el factor monomio a la izquierda, pero también puede aparecer a la derecha. \[(3+4) \cdot 2=3 \cdot 2+4 \cdot 2 \nonumber \]Nuevamente, ambos lados igualan\(14\). Entonces, si el monomio aparece a la izquierda o a la derecha no hace diferencia; es decir,\(a(b + c)=ab + ac\) y\((b + c)a = ba + ca\) dar el mismo resultado. En cada caso,\(a\) multiplicas por ambos términos de\(b + c\).

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{8}\)

Multiplicar:\((2x + 5)(3x + 2)\)

Solución

Tenga en cuenta que\((2x + 5)(3x + 2)\) tiene la forma\((b + c)a\), donde\(a\) está el binomio\(3x+2\). Porque\((b+c){\color {Red}a} = b{\color {Red}a}+c{\color {Red}a}\), vamos a\(3x+2\) multiplicar por ambos términos\(2x + 5\) de la siguiente manera.

\[(2x + 5){\color {Red}(3x + 2)}=2x{\color {Red}(3x + 2)}+5{\color {Red}(3x + 2)} \nonumber \]

Ahora distribuimos monomios tiempos polinomios, luego combinamos términos similares.

\[\begin{array}{l}{=6 x^{2}+4 x+15 x+10} \\ {=6 x^{2}+19 x+10}\end{array} \nonumber \]

Por lo tanto,\((2 x+5)(3 x+2)=6 x^{2}+19 x+10\)

Ejercicio\(\PageIndex{8}\)

Multiplicar:\((3x + 4)(5x + 1)\)

- Contestar

-

\(15 x^{2}+23 x+4\)

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{9}\)

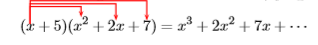

Multiplicar:\((x+5)\left(x^{2}+2 x+7\right)\)

Solución

Tenga en cuenta que\((x+5)(x^2 +2x+7)\) tiene la forma\((b+c)a\), donde\(a\) está el trinomio\(x^2 +2x+7\). Porque\((b+c){\color {Red}a} = b{\color {Red}a}+c{\color {Red}a}\), vamos a\(x^2 +2x+7\) multiplicar por ambos términos\(x + 5\) de la siguiente manera.

\[(x+5){\color {Red}\left(x^{2}+2 x+7\right)}=x{\color {Red}\left(x^{2}+2 x+7\right)}+5{\color {Red}\left(x^{2}+2 x+7\right)} \nonumber \]

Ahora distribuimos monomios tiempos polinomios, luego combinamos términos similares.

\[\begin{array}{l}{=x^{3}+2 x^{2}+7 x+5 x^{2}+10 x+35} \\ {=x^{3}+7 x^{2}+17 x+35}\end{array} \nonumber \]

Por lo tanto,\((x+5)\left(x^{2}+2 x+7\right)=x^{3}+7 x^{2}+17 x+35\)

Ejercicio\(\PageIndex{9}\)

Multiplicar:\((z+4)\left(z^{2}+3 z+9\right)\)

- Contestar

-

\(z^{3}+7 z^{2}+21 z+36\)

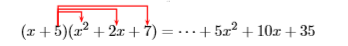

Acelerar un poco las cosas

Reexaminemos Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{9}\) con la esperanza de desenterrar un patrón que permita que la multiplicación de polinomios proceda más rápidamente con menos trabajo. Observe el primer paso del Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{9}\).

\[(x+5){\color {Red}\left(x^{2}+2 x+7\right)}=x{\color {Red}\left(x^{2}+2 x+7\right)}+5{\color {Red}\left(x^{2}+2 x+7\right)} \nonumber \]

Tenga en cuenta que el primer producto a la derecha es el resultado de tomar el producto del primer término de\(x + 5\) y\(x^2 +2x + 7\). De igual manera, el segundo producto a la derecha es el resultado de tomar el producto del segundo término de\(x + 5\) y\(x^2 +2x + 7\). A continuación, examinemos el resultado del segundo paso.

\[(x+5)\left(x^{2}+2 x+7\right)=x^{3}+2 x^{2}+7 x+5 x^{2}+10 x+35 \nonumber \]

Los tres primeros términos de la derecha son el resultado de multiplicar\(x\) tiempos\(x^2+2x+7\).

El segundo conjunto de tres términos a la derecha son el resultado de multiplicar\(5\) tiempos\(x^2 +2x + 7\).

Estas notas sugieren un atajo eficiente. Para multiplicar\(x+5\) los tiempos\(x^2 +2x+7\),

- Multiplicar\(x\) veces cada término de\(x^2 +2x + 7\).

- Multiplicar\(5\) veces cada término de\(x^2 +2x + 7\).

- Combina términos similares.

Este proceso tendría la siguiente apariencia.

\[\begin{aligned}(x+5)\left(x^{2}+2 x+7\right) &=x^{3}+2 x^{2}+7 x+5 x^{2}+10 x+35 \\ &=x^{3}+7 x^{2}+17 x+35 \end{aligned} \nonumber \]

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{10}\)

Utilice la técnica de atajo descrita anteriormente para simplificar:\((2 y-6)\left(3 y^{2}+4 y+11\right)\)

Solución

Multiplicar\(2y\) veces cada término de\(3y^2 +4 y + 11\), luego\(−6\) multiplicar por cada término de\(3y^2 +4y + 11\). Por último, combina términos similares.

\[\begin{aligned}(2 y-6)\left(3 y^{2}+4 y+11\right) &=6 y^{3}+8 y^{2}+22 y-18 y^{2}-24 y-66 \\ &=6 y^{3}-10 y^{2}-2 y-66 \end{aligned} \nonumber \]

Ejercicio\(\PageIndex{10}\)

Multiplicar:\((3 x+2)\left(4 x^{2}-x+10\right)\)

- Contestar

-

\(12 x^{3}+5 x^{2}+28 x+20\)

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{11}\)

Utilice la técnica de atajo para simplificar\((a+b)^{2}\)

Solución

Para simplificar\((a+b)^2\), primero debemos escribir\(a+b\) como factor dos veces.

\[(a+b)^{2}=(a+b)(a+b) \nonumber \]

A continuación, multiplicar a veces ambos términos de\(a + b\), multiplicar b por ambos términos de\(a + b\), luego combinar términos similares.

\[\begin{array}{l}{=a^{2}+a b+b a+b^{2}} \\ {=a^{2}+2 a b+b^{2}}\end{array} \nonumber \]

Tenga en cuenta que\(ab = ba\) debido a que la multiplicación es conmutativa, entonces\(ab + ba =2ab\).

Ejercicio\(\PageIndex{11}\)

Multiplicar:\((3 y-2)^{2}\)

- Contestar

-

\(9 y^{2}-12 y+4\)

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{12}\)

Utilice la técnica de atajo para simplificar:\(\left(x^{2}+x+1\right)\left(x^{2}-x-1\right)\)

Solución

Esta vez el primer factor contiene tres términos,\(x^2\),\(x\), y\(1\), así que primero\(x^2\) multiplicamos por cada término de\(x^2 −x−1\), luego\(x\) por cada término de\(x^2 −x−1\), y\(1\) por cada término de\(x^2 −x−1\). Entonces combinamos términos similares.

\[\begin{aligned}\left(x^{2}+x+1\right)\left(x^{2}-x-1\right) &=x^{4}-x^{3}-x^{2}+x^{3}-x^{2}-x+x^{2}-x-1 \\ &=x^{4}-x^{2}-2 x-1 \end{aligned} \nonumber \]

Ejercicio\(\PageIndex{12}\)

Multiplicar:\(\left(a^{2}-2 a+3\right)\left(a^{2}+2 a-3\right)\)

- Contestar

-

\(a^{4}-4 a^{2}+12 a-9\)

Algunas aplicaciones

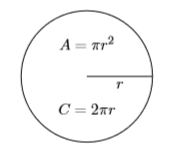

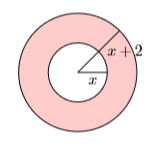

Recordemos que el área de un círculo de radio\(r\) se encuentra usando la fórmula\(A = πr^2\). La circunferencia (distancia alrededor) de un círculo de radio\(r\) se encuentra usando la fórmula\(C =2πr\) (ver Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\)).

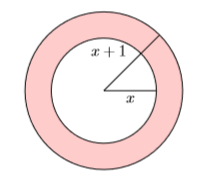

Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{13}\)

En la Figura\(\PageIndex{2}\) se representan dos círculos concéntricos (mismo centro). El círculo interior tiene radio\(x\) y el círculo exterior tiene radio\(x + 1\). Encuentra el área de la región sombreada (llamada anillo) en función de\(x\).

Solución

Podemos encontrar el área de la región sombreada restando el área del círculo interno del área del círculo exterior.

\[A=\text { Area of outer circle - Area of inner circle} \nonumber \]

Utilizamos la fórmula\(A = πr^2\) para calcular el área de cada círculo. Debido a que el círculo exterior tiene radio\(x+1\), tiene área\(π(x+1)^2\). Debido a que el círculo interno tiene radio\(x\), tiene área\(πx^2\).

\[=\pi(x+1)^{2}-\pi x^{2} \nonumber \]

A continuación, expandiremos\((x + 1)^2\), luego combinaremos términos similares.

\[\begin{array}{l}{=\pi(x+1)(x+1)-\pi x^{2}} \\ {=\pi\left(x^{2}+x+x+1\right)-\pi x^{2}} \\ {=\pi\left(x^{2}+2 x+1\right)-\pi x^{2}}\end{array} \nonumber \]

Por último, distribuir\(π\) veces cada término de\(x^2 +2x + 1\), luego combinar términos similares.

\[\begin{array}{l}{=\pi x^{2}+2 \pi x+\pi-\pi x^{2}} \\ {=2 \pi x+\pi}\end{array} \nonumber \]

De ahí que el área de la región sombreada sea\(A =2πx+ π\).

Ejercicio\(\PageIndex{13}\)

A continuación se muestran dos círculos concéntricos. El círculo interior tiene radio\(x\) and the outer circle has radius \(x + 2\). Find the area of the shaded region as a function of \(x\).

- Contestar

-

\(4 \pi x+4 \pi\)

Example \(\PageIndex{14}\)

The demand for widgets is a function of the unit price, where the demand is the number of widgets the public will buy and the unit price is the amount charged for a single widget. Suppose that the demand is given by the function \(x = 270−0.75p\), where \(x\) is the demand and \(p\) is the unit price. Note how the demand decreases as the unit price goes up (makes sense). Use the graphing calculator to determine the unit price a retailer should charge for widgets so that his revenue from sales equals \(\$20,000\).

Solution

To determine the revenue \((R)\), you multiply the number of widgets sold \((x)\) by the unit price \((p)\).

\[R=xp \label {Eq5.6.1} \]

However, we know that the number of units sold is the demand, given by the formula

\[x = 270−0.75p \label {Eq5.6.2} \]

Substitute equation \(\ref {Eq5.6.2}\) into equation \(\ref {Eq5.6.1}\) to obtain the revenue as a function of the unit price.

\[R = (270−0.75p)p \nonumber \]

Expand.

\[R=270 p-0.75 p^{2} \label {Eq5.6.3} \]

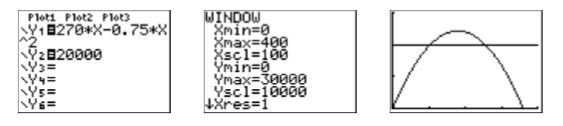

We’re asked to determine the unit price that brings in a revenue of \(\$20,000\). Substitute \(\$20,000\) for \(R\) in equation \(\ref {Eq5.6.3}\).

\[20000=270 p-0.75 p^{2} \label {Eq5.6.4} \]

Enter each side of equation \(\ref {Eq5.6.4}\) into the Y= menu of your calculator (see the first image in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). After some experimentation, we settled on the WINDOW parameters shown in the second image of Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\). After making these settings, push the GRAPH button to produce the graph shown in the third image in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\).

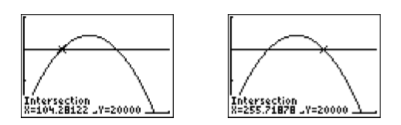

Note that the third image in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) shows that there are two solutions, that is, two ways we can set the unit price to obtain a revenue of \(\$20,000\). To find the first solution, select 5:intersect from the CALC menu, press ENTER in response to “First curve,” press ENTER in response to “Second curve,” then move your cursor closer to the point of intersection on the left and press ENTER in response to “Guess.” The result is shown in the first image in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\).

Repeat the process to find the second point of intersection. The result is shown in the second image in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\).

Note

In this example, the horizontal axis is actually the \(p\)-axis. So when we set \(\mathrm{Xmin}\) and \(\mathrm{Xmax}\), we’re actually setting bounds on the \(p\)-axis.

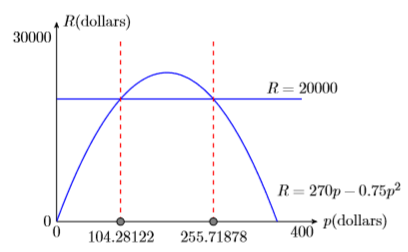

Reporting the solution on your homework:

Duplicate the image in your calculator’s viewing window on your homework page. Use a ruler to draw all lines, but freehand any curves.

- Label the horizontal and vertical axes with \(p\) and \(R\), respectively (see Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)). Include the units (dollars and dollars).

- Place your WINDOW parameters at the end of each axis (see Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)).

- Label each graph with its equation (see Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)).

- Drop a dashed vertical line through each point of intersection. Shade and label the \(p\)-values of the points where the dashed vertical lines cross the \(p\)-axis. These are the solutions of the equation \(20000 = 270p− 0.75p^2\) (see Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)).

Rounding to the nearest penny, setting the unit price at either \(\$104.28\) or \(\$255.72\) will bring in a revenue of \(\$20,000\).

Exercise \(\PageIndex{14}\)

Suppose that the demand for gadgets is given by the function \(x = 320−1.5p\), where \(x\) is the demand and \(p\) is the unit price. Use the graphing calculator to determine the unit price a retailer should charge for gadgets so that her revenue from sales equals \(\$12,000\).

- Answer

-

\(\$ 48.55\) or \(\$ 164.79\)