5.2: Grupos diedros

- Page ID

- 111055

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

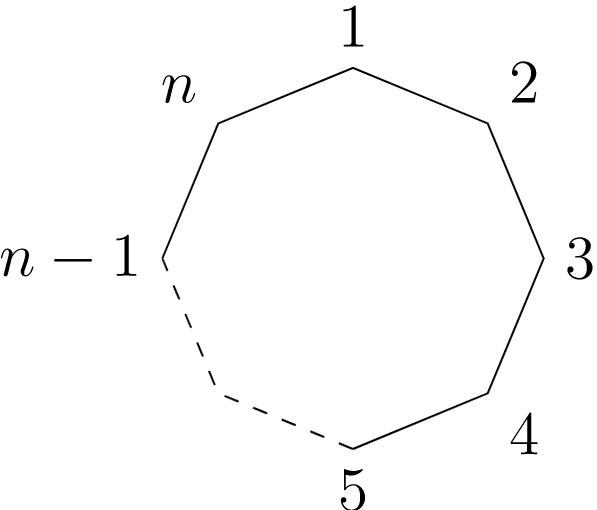

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Otro tipo especial de grupo de permutación es el grupo diedro. Recordemos el grupo de simetría de un triángulo equilátero en el Capítulo 3. Dichos grupos consisten en los movimientos rígidos de un polígono o\(n\)\(n\) -gon de lados regulares. Para\(n = 3, 4, \ldots\text{,}\) definimos el enésimo grupo diedro como el grupo de movimientos rígidos de un\(n\) -gon regular. Denotaremos este grupo por\(D_n\text{.}\) Podemos numerar los vértices de un\(n\) -gon regular por\(1, 2, \ldots, n\) (Figura 5.19). Observe que hay exactamente\(n\) opciones para reemplazar el primer vértice. Si reemplazamos el primer vértice por\(k\text{,}\) entonces el segundo vértice debe ser reemplazado ya sea por vértice\(k+1\) o por vértice de\(k-1\text{;}\) ahí, hay\(2n\) posibles movimientos rígidos del\(n\) -gon. Resumimos estos resultados en el siguiente teorema.

\(Figure \text { } 5.19.\)Un\(n\) -gon regular

El grupo diedro,\(D_n\text{,}\) es un subgrupo\(S_n\) de orden\ (2n\ text { . }\

El grupo\(D_n\text{,}\)\(n \geq 3\text{,}\) consta de todos los productos de los dos elementos\(r\) y\(s\text{,}\) satisfaciendo las relaciones

- Prueba

-

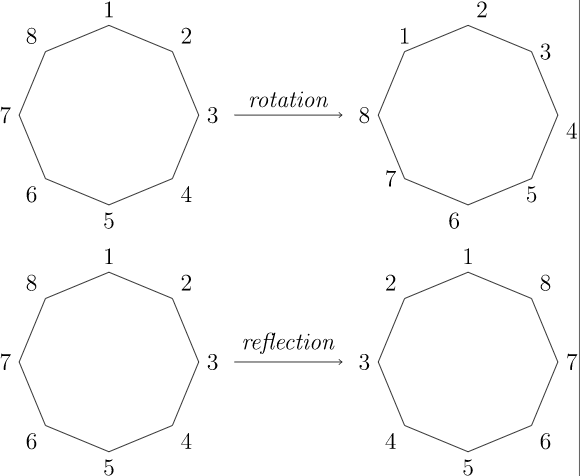

Los posibles movimientos de un\(n\) -gon regular son reflexiones o rotaciones (Figura 5.22). Hay rotaciones exactamente\(n\) posibles:

\[ \identity, \frac{360^{\circ} }{n}, 2 \cdot \frac{360^{\circ} }{n}, \ldots, (n-1) \cdot \frac{360^{\circ} }{n}\text{.} \nonumber \]Denotaremos la rotación\(360^{\circ} /n\) por\(r\text{.}\) La rotación\(r\) genera todas las demás rotaciones. Es decir,

\[ r^k = k \cdot \frac{360^{\circ} }{n}\text{.} \nonumber \] \(Figure \text { } 5.22.\)Rotaciones y reflejos de un\(n\) -gon regular

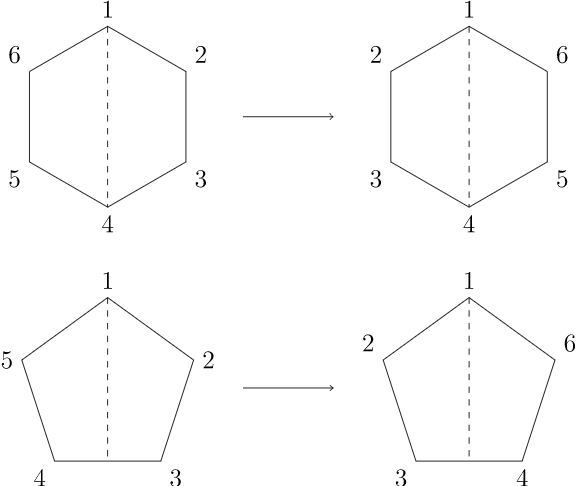

\(Figure \text { } 5.22.\)Rotaciones y reflejos de un\(n\) -gon regularEtiquetar los\(n\) reflejos\(s_1, s_2, \ldots, s_n\text{,}\) donde\(s_k\) está el reflejo que deja\(k\) fijo el vértice. Hay dos casos de reflexiones, dependiendo de si\(n\) es par o impar. Si hay un número par de vértices, entonces dos vértices quedan fijos por una reflexión, y\(s_1 = s_{n/2 + 1}, s_2 = s_{n/2 + 2}, \ldots, s_{n/2} = s_n\text{.}\) si hay un número impar de vértices, entonces solo un vértice queda fijado por una reflexión y\(s_1, s_2, \ldots, s_n\) son distintos (Figura 5.23). En cualquier caso, el orden de cada uno\(s_k\) es de dos. Dejar\(s = s_1\text{.}\) Entonces\(s^2 = 1\) y\(r^n = 1\text{.}\) Dado que cualquier movimiento rígido\(t\) del\(n\) -gon reemplaza el primer vértice por el vértice\(k\text{,}\) el segundo vértice debe ser reemplazado por cualquiera\(k+1\) o por\(k-1\text{.}\) Si el segundo vértice es reemplazado por\(k+1\text{,}\) entonces\(t = r^k\text{.}\) Si el segundo vértice se sustituye por\(k-1\text{,}\) entonces\(t = r^k s\text{.}\) 2 Por lo tanto,\(r\) y\(s\) generar Es\(D_n\text{.}\) decir,\(D_n\) consiste en todos los productos finitos de\(r\) y\(s\text{,}\)

\[ D_n = \{1, r, r^2, \ldots, r^{n-1}, s, rs, r^2 s, \ldots, r^{n-1} s\}\text{.} \nonumber \]Dejaremos la prueba de que\(srs = r^{-1}\) como ejercicio.

Ya que estamos en un grupo abstracto, vamos a adoptar la convención de que los elementos del grupo se multiplican de izquierda a derecha. \(Figure \text { } 5.23.\)Tipos de reflejos de un\(n\) -gon regular

\(Figure \text { } 5.23.\)Tipos de reflejos de un\(n\) -gon regular