11.9: Flujos alrededor de los cilindros

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Teorema del círculo de Milne-Thomson

El teorema de Milne-Thomson nos permite insertar un círculo en un flujo bidimensional y ver cómo se ajusta el flujo. Primero declararemos y probaremos el teorema.

Sif(z) es un potencial complejo con todas sus singularidades afuera|z|=R entonces

Φ(z)=f(z)+¯f(R2¯z)

es un potencial complejo con racionalidad|z|=R y las mismas singularidades quef en la región|z|>R.

- Prueba

-

Primera nota queR2/¯z es el reflejo dez en el círculo|z|=R.

A continuación tenemos que ver que¯f(R2/¯z) es analítico para|z|>R. Por supuestof(z) es analítico para|z|<R, por lo que se puede expresar como una serie de Taylor

f(z)=a0+a1z+a2z2+ ...

Por lo tanto,

¯f(R2¯z)=¯a0+¯a1R2z+¯a2(R2z)2+ ...

Todas las singularidades def están afuera|z|=R, por lo que la serie Taylor en la Ecuación 11.10.2 converge para|z|≤R. Esto significa que la serie Laurent en la Ecuación 11.10.3 converge para|z|≥R. Es decir,¯f(R2/¯z) es analítico|z|≥R, es decir, no introduce singulares alΦ(z) exterior|z|=R.

Lo último que hay que mostrar es que|z|=R es una racionalización paraΦ(z). Esto sigue porque paraz=Reiθ

Φ(Reiθ)=f(Reiθ+¯f(Reiθ)

es real. Por lo tanto

ψ(Reiθ=Im(Φ(Reiθ)=0.

Ejemplos

f(z)Piense en representar el flujo, posiblemente con fuentes o vórtices afuera|z|=R. EntoncesΦ(z) representa el nuevo flujo cuando se coloca un obstáculo circular en el flujo. Aquí hay algunos ejemplos.

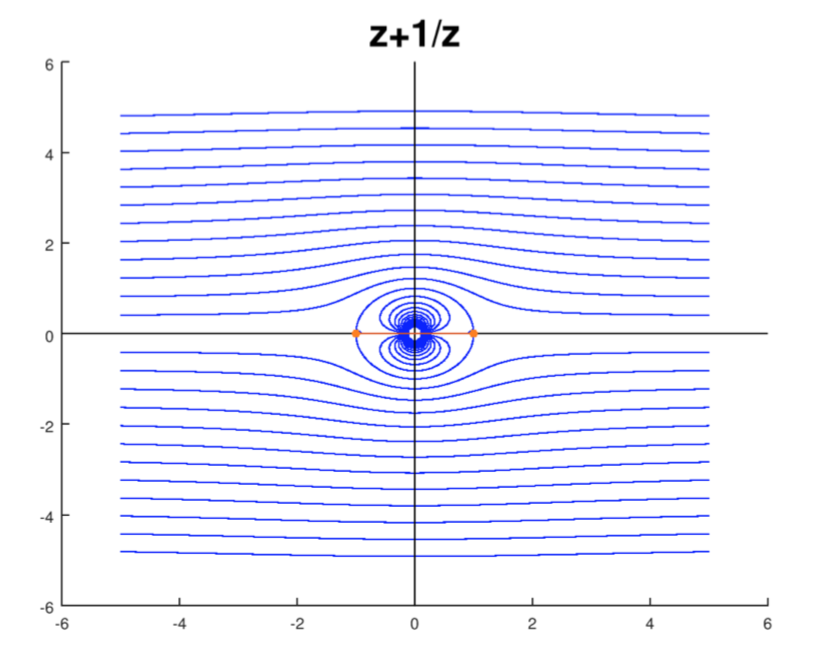

Sabemos por el Tema 6 quef(z)=z es el complejo potencial de flujo uniforme hacia la derecha. Entonces,

Φ(z)=z+R2/z

es el potencial de flujo uniforme alrededor de un círculo de radioR centrado en el origen.

Flujo uniforme alrededor de un círculo

Sólo porque se ven bien, la figura incluye líneas de racionalización dentro del círculo. Estos no interactúan con el flujo fuera del círculo.

Tenga en cuenta que a medida quez obtiene un flujo grande se ve uniforme. Podemos ver esto analíticamente porque

Φ′(z)=1−R2/z2

va a 1 comoz se hace grande. (Recordemos que el campo de velocidad es (ϕx,ϕy), dondeΦ=ϕ+iψ ...)

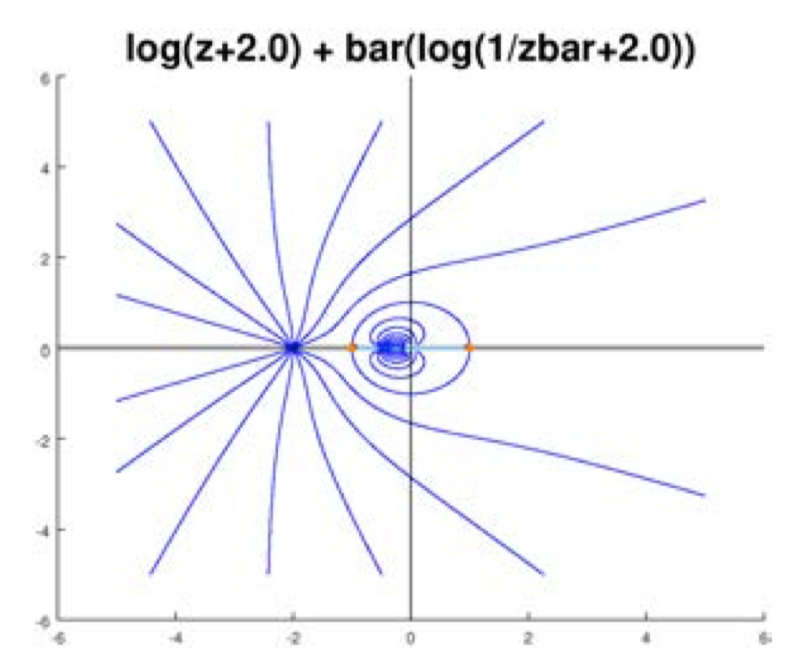

Aquí la fuente está enz=−2 (fuera del círculo unitario) con potencial complejo

f(z)=log(z+2).

Con el corte de rama apropiado las singularidades de tambiénf están afuera|z|=1. Así podemos aplicar Milne-Thomson y obtener

Φ(z)=log(z+2)+¯log(1¯z+2)

Flujo fuente alrededor de un círculo

Sabemos que lejos del origen el flujo debe verse igual que un flujo con solo una fuentez=−2.

Veamos esto analíticamente. Primero señalamos un dato útil:

Sig(z) es analítico entonces así esh(z)=¯g(¯z) yh′(z)=¯g′(¯z).

- Prueba

-

Utilice la serie Taylorg para obtener la serie Taylor parah y luego compareh′(z) y¯g′(¯z).

Usando esto tenemos

Φ′(z)=1z+2−1z(1+2z)

Para grandesz el segundo término decae mucho más rápido que el primero, por lo que

Φ′(z)≈1z+2.

Es decir, lejos dez=0, el campo de velocidad se parece al campo de velocidad paraf(z), es decir, el campo de velocidad de una fuente enz=−2.

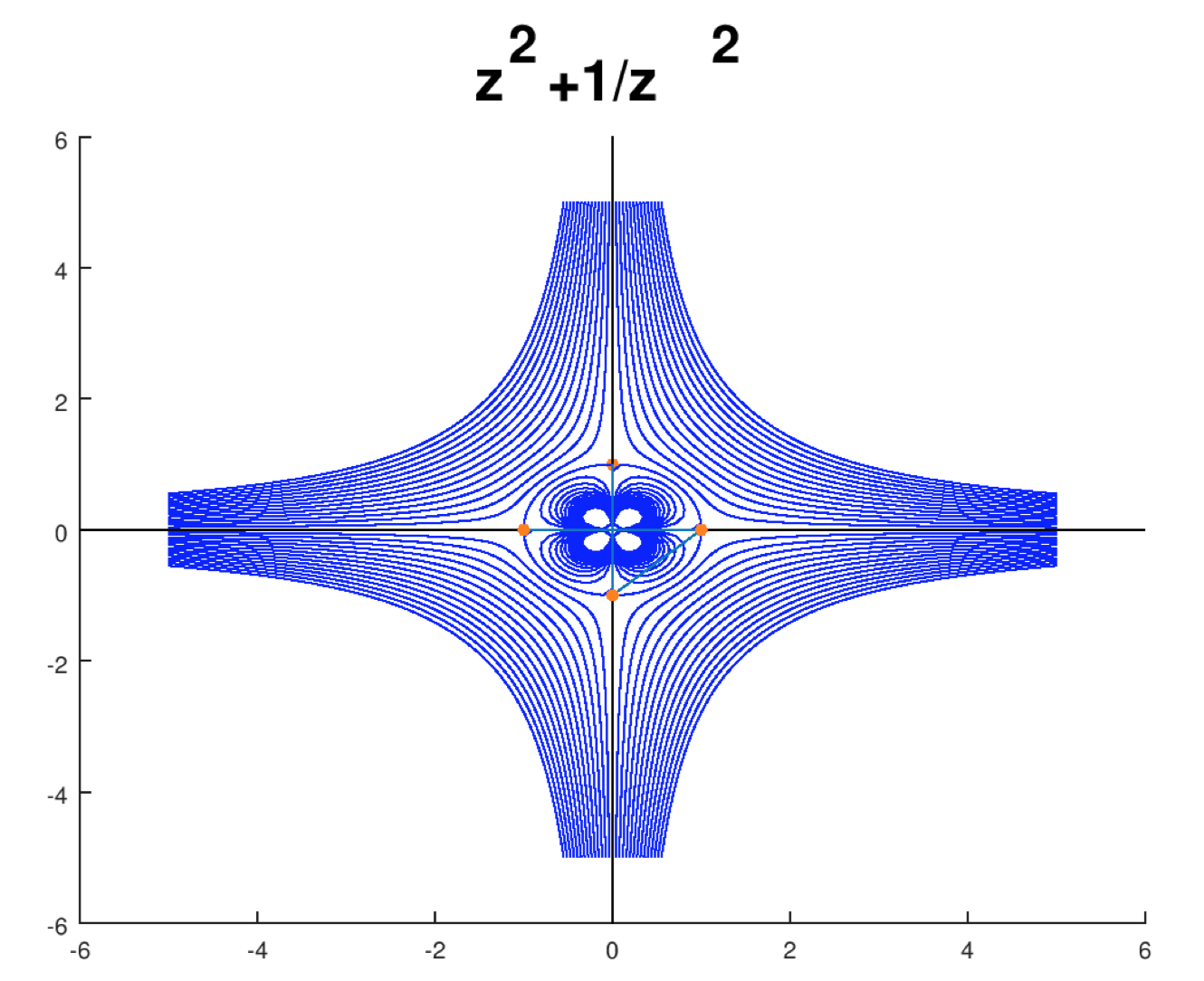

Si usamos

g(z)=z2

podemos transformar un flujo desde el semiplano superior al primer cuadrante

Flujo de origen alrededor de un cuarto de esquina circular