4.6: Serie de Fourier para funciones pares e impares

- Page ID

- 113694

Observe que en la serie de Fourier de la onda cuadrada (4.5.3) todos los coeficientes\(a_n\) desaparecen, la serie solo contiene senos. Este es un fenómeno muy general para las llamadas funciones pares e impares.

Una función se llama incluso si\(f(-x)=f(x)\), e.g\(\cos(x)\).

Una función se llama impar si\(f(-x)=-f(x)\), e.g\(\sin(x)\).

Estos tienen propiedades algo diferentes a los números pares e impares:

- La suma de dos funciones pares es par, y de dos impares impares.

- El producto de dos funciones pares o dos impares es par.

- El producto de una función par y otra impar es impar.

¿Cuál de las siguientes funciones es par o impar?

a)\(sin (2 x)\), b)\(sin ( x) cos ( x)\), c)\(tan ( x)\), d)\(x^2\), e)\(x^3\), f)\(|x|\)

- Contestar

-

par: d, f; impar: a, b, c, e.

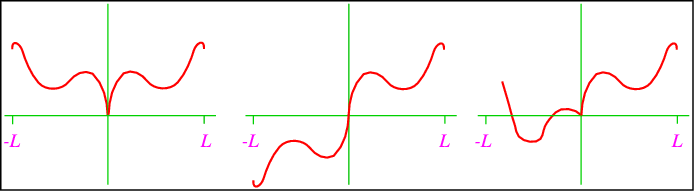

Ahora bien, si nos fijamos en una serie de Fourier, la serie coseno de Fourier\[f(x) = \frac{a_0}{2} + \sum_{n=1}^\infty a_n \cos\frac{n\pi}{L}x \nonumber \] describe una función par (¿por qué?) , y la serie sinusoidal de Fourier\[f(x) = \sum_{n=1}^\infty b_n \sin\frac{n\pi}{L}x \nonumber \] una función impar. Estas series son interesantes por sí mismas, pero juegan un papel especialmente importante para las funciones definidas en la mitad del intervalo de Fourier, es decir, on en\([0,L]\) lugar de\([-L,L]\). Hay tres formas posibles de definir una serie de Fourier de esta manera, ver Fig. \(\PageIndex{1}\)

- Continuar\(f\) como una función parejo, así que eso\(f'(0)=0\).

- Continuar\(f\) como una función impar, así que eso\(f(0)=0\).

Por supuesto, todos estos conducen a diferentes series de Fourier, que representan la misma función en\([0,L]\). La utilidad de las series pares e impares de Fourier se relaciona con la imposición de condiciones límite. Una serie de coseno de Fourier tiene\(df/dx = 0\) at\(x=0\), y la serie sinusoidal de Fourier tiene\(f(x=0)=0\). Permítanme revisar la primera de estas declaraciones:\[\frac{d}{dx} \left[\frac{a_0}{2} + \sum_{n=1}^\infty a_n \cos\frac{n\pi}{L}x \right] = -\frac{\pi}{L}\sum_{n=1}^\infty n a_n \sin\frac{n\pi}{L}x =0\quad\text{at $x=0$.} \nonumber \]

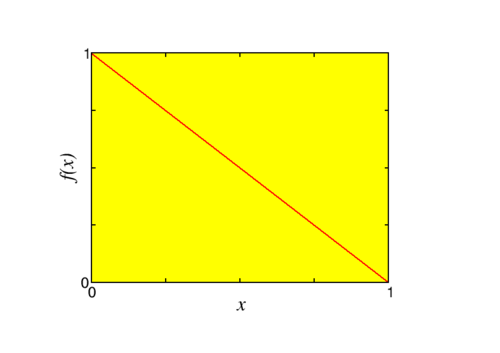

Como ejemplo mira la función\(f(x) = 1-x\),\(0 \leq x \leq 1\), con una continuación uniforme en el intervalo\([-1,1]\). Encontramos\[\begin{aligned} a_0 & = \frac{2}{1} \int_0^1 (1-x) dx = 1 \nonumber\\ a_n &= 2 \int_0^1 (1-x) \cos n\pi x dx\nonumber\\ &= \left.\left\{ \frac{2}{n\pi} \sin n\pi x - \frac{2}{n^2\pi^2} [\cos n\pi x + n \pi x \sin n\pi x] \right\} \right|_0^1 \nonumber\\&= \begin{cases} 0 & \text{if $n$ even}\\ \frac{4}{n^2\pi^2}&\text{if $n$ is odd} \end{cases}\quad.\end{aligned} \nonumber \] Así, cambiando las variables definiendo de\(n=2m+1\) manera que en una suma sobre todas las\(m\)\(n\) carreras sobre todos los números impares,\[f(x) = \frac{1}{2} + \frac{4}{\pi^2}\sum_{m=0}^{\infty} \frac{1}{(2m+1)^2} \cos(2m+1)\pi x. \nonumber \]