4.5: ¿Cuándo es una Serie de Fourier?

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Las series discutidas antes solo son útiles ya que podemos asociar una función con ellas. ¿Cómo podemos hacer eso?

Supongamos que la función periódicaf(x) tiene una representación en serie de Fourier (intercambiar la suma e integración, y usar ortogonalidad),

f(x)=a02+∑n=1[ancos(nπxL)+bnsin(nπxL)]

Ahora podemos usar la ortogonalidad de las funciones trigonométricas para encontrar que

1L∫L−Lf(x)⋅1dx=a0

1L∫L−Lf(x)⋅cos(nπxL)dx=an

1L∫L−Lf(x)⋅sin(nπxL)dx=an

Esto define los coeficientes de Fourier para un dadof(x). Si todos estos coeficientes existen hemos definido una serie de Fourier, de cuya convergencia hablaremos en una conferencia posterior.

Una propiedad importante de las series de Fourier se da en el lema de Parseval:

∫L−L(f(x))2dx=La202+L∞∑n=1(a2n+b2n).

Esto parece una trivialidad, hasta que uno se da cuenta de lo que hemos hecho: hemos vuelto a intercambiar una suma infinita y una integración. Hay muchos casos en los que un intercambio de este tipo falla, y en realidad hace una declaración fuerte sobre el conjunto ortogonal cuando se mantiene. Esta propiedad generalmente se conoce como integridad. Solo discutiremos conjuntos completos en estas conferencias.

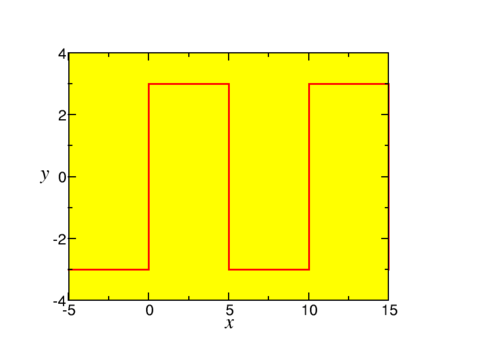

Ahora estudiemos un ejemplo. Consideramos una onda cuadrada (este ejemplo volverá algunas veces)

f(x)={−3if −5+10n<x<10n3if 10n<x<5+10n,

donden es un número entero, como se esboza en la Fig. 4.5.1.

Esta función no está definida enx=5n. Eso lo vemos fácilmenteL=5. Los coeficientes de Fourier sona0=15∫0−5−3dx+15∫503dx=0an=15∫0−5−3cos(nπx5)+15∫503cos(nπx5)=0bn=15∫0−5−3sin(nπx5)+15∫503sin(nπx5)=3nπcos(nπx5)|0−5−3nπcos(nπx5)|50=6nπ[1−cos(nπ)]={12nπif n odd0if n even Y así (n=2m+1)f(x)=12π∑m=012m+1sin((2m+1)πx5).

¿Qué pasa si aplicamos el teorema de Parseval a esta serie?

- Contestar

-

Encontramos∫5−59dx=5144π2∞∑m=0(12m+1)2 Que se puede utilizar para mostrar que∞∑m=0(12m+1)2=π28.