5.2: Bisectriz perpendicular

- Page ID

- 114848

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

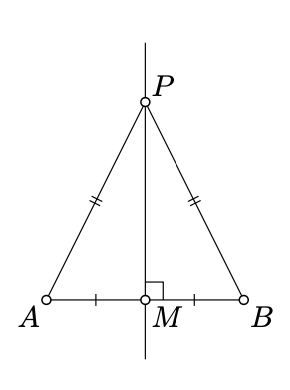

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Supongamos que\(M\) es el punto medio del segmento\([AB]\); es decir,\(M \in (AB)\) y\(AM = MB\).

La línea\(\ell\) que pasa a través\(M\) y perpendicular a\((AB)\), se llama la bisectriz perpendicular al segmento\([AB]\).

Dados distintos puntos\(A\) y\(B\), todos los puntos equidistantes de\(A\)\(B\) y no otros se encuentran en la bisectriz perpendicular a\([AB]\).

- Prueba

-

Dejar\(M\) ser el punto medio de\([AB]\).

Asumir\(PA = PB\) y\(P \ne M\). Según SSS (Teorema 4.4.1),\(\triangle AMP \cong \triangle BMP\). De ahí

\(\measuredangle AMP = \pm \measuredangle BMP.\)

Ya que\(A \ne B\), tenemos “-” en la fórmula anterior. Además,

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {\pi} & = & {\measuredangle AMB \equiv} \\ {} & \equiv & {\measuredangle AMP + \measuredangle PMB \equiv} \\ {} & \equiv & {2 \cdot \measuredangle AMP.} \end{array}\]

Es decir,\(\measuredangle AMP = \pm \dfrac{\pi}{2}\). Por lo tanto,\(P\) se encuentra en la bisectriz perpendicular.

Para probar lo contrario, supongamos que\(P\) es cualquier punto en la bisectriz perpendicular a\([AB]\) y\(P \ne M\). Entonces\(\measuredangle AMP = \pm \dfrac{\pi}{2}\),\(\measuredangle BMP = \pm \dfrac{\pi}{2}\) y\(AM = BM\). Por SAS,\(\triangle AMP \cong \triangle BMP\); en particular,\(AP = BP\).

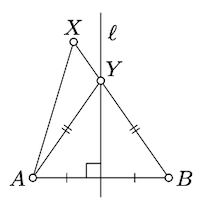

Dejar\(\ell\) ser la bisectriz perpendicular al segmento\([AB]\) y\(X\) ser un punto arbitrario en el plano.

Demostrar que\(AX < BX\) si y sólo si\(X\) y\(A\) se encuentran en el mismo lado de\(\ell\).

- Pista

-

Asumir\(X\) y\(A\) acostarse del mismo lado de\(\ell\).

Tenga en cuenta que\(A\) y\(B\) se encuentran en el lado opuesto de\(\ell\). Por lo tanto, por Corolario 3.4.1,\([AX]\) no se cruza\(\ell\) y se\([BX]\) cruza\(\ell\); supongamos que\(Y\) denota el punto de intersección.

Tenga en cuenta que\(BX = AY + YX \ge AX\). Ya que\(X \not\in \ell\), por Teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\) tenemos\(BX \ne BA\). Por lo tanto\(BX > AX\).

De esta manera probamos la parte del “si”. Para probar la parte de “sólo si”, es necesario cambiar\(A\)\(B\) y repetir el argumento anterior.

Dejar\(ABC\) ser un triángulo no degenerado. Demostrar que

\(AC > BC \Leftrightarrow |\measuredangle ABC| > |\measuredangle CAB|.\)

- Pista

-

Aplicar Ejercicio\(\PageIndex{1}\), Teorema 4.2.1 y Ejercicio 3.1.2.