4.2: Triángulos similares

- Page ID

- 114612

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Se dice que dos triángulos son similares si tienen conjuntos iguales de ángulos. En la Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\),\(\triangle ABC\) es similar a\(\triangle DEF.\) Los ángulos que son iguales se denominan ángulos correspondientes. En la Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\),\(\angle A\) corresponde a\(\angle D\),\(\angle B\) corresponde a\(\angle E\), y\(\angle C\) corresponde a\(\angle F\). Los lados que unen vértices correspondientes se denominan lados correspondientes. En la Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\),\(AB\) corresponde a\(DE\),\(BC\) corresponde a\(EF\), y\(AC\) corresponde a\(DF\). El símbolo para similar es\(\sim\). La declaración\(\triangle ABC \sim \triangle DEF\) de similitud siempre se escribirá para que los vértices correspondientes aparezcan en el mismo orden.

Para los triángulos en Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\), también podríamos escribir\(\triangle BAC \sim \triangle BDF\) o\(\triangle ACB \sim \triangle DFE\) pero nunca\(\triangle ABC \sim \triangle EDF\) ni\(\triangle ACB \sim \triangle DEF\).

Podemos decir qué lados corresponden a partir de la declaración de similitud. Por ejemplo, si\(\triangle ABC \sim \triangle DEF\), entonces lado\(AB\) corresponde a lado\(DE\) porque ambas son las dos primeras letras. \(BC\)corresponde a\(EF\) porque ambas son las dos últimas letras,\(AC\) corresponde a\(DF\) porque ambas constan de la primera y la última letra.

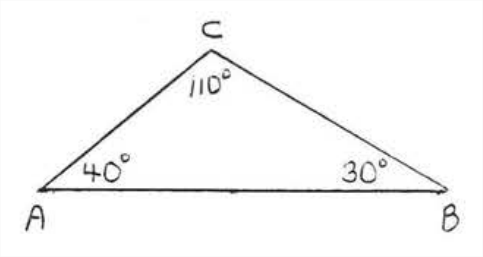

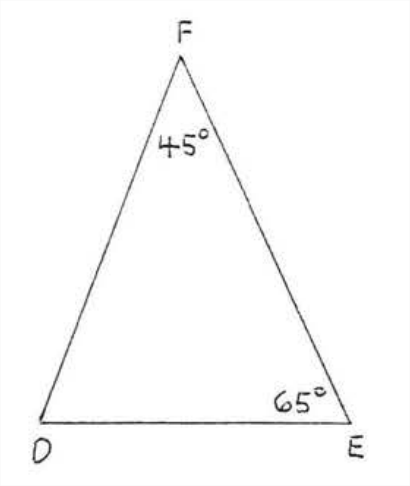

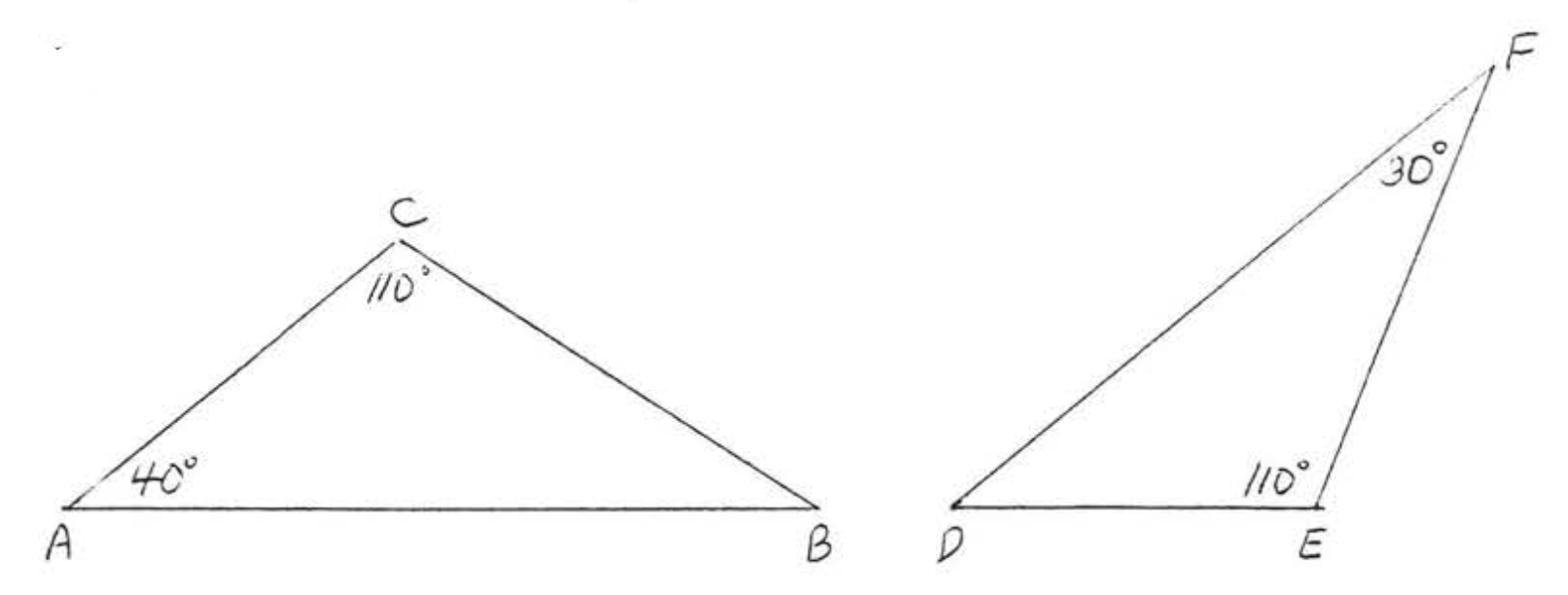

Determina si los triángulos son similares, y si es así, escribe la declaración de similitud:

Solución

\[\angle C = 180^{\circ} - (65^{\circ} + 45^{\circ}) = 180^{\circ} - 110^{\circ} = 70^{\circ} \nonumber\]

\[\angle D = 180^{\circ} - (65^{\circ} + 45^{\circ}) = 180^{\circ} - 110^{\circ} = 70^{\circ} \nonumber\]

Por lo tanto ambos triángulos tienen los mismos ángulos y\(\triangle ABC \sim \triangle EFD\).

Respuesta:\(\triangle ABC \sim \triangle EFD\).

El ejemplo A sugiere que para probar similitud solo es necesario saber que dos de los ángulos correspondientes son iguales:

Dos triángulos son similares si dos ángulos de uno equivalen a dos ángulos del otro\((AA = AA)\).

En la Figura\(\PageIndex{2}\), \(\triangle ABC \sim \triangle DEF\) because \(\angle A = \angle D\) and \(\angle B = \angle E\).

- Prueba

-

\(\triangle C = 180^{\circ} - (\angle A + \angle B) = 180^{\circ} - (\angle D + \angle E) = \angle F\).

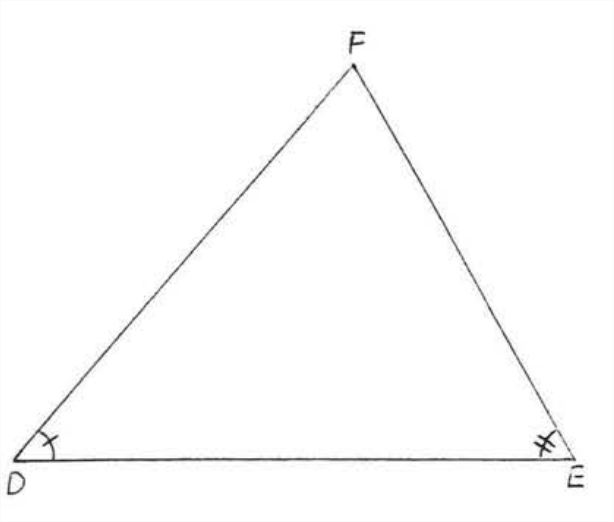

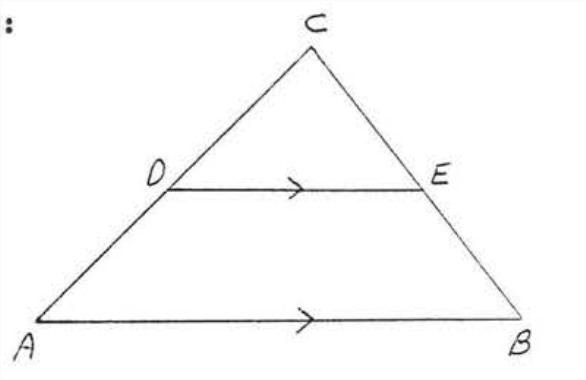

Determina qué triángulos son similares y escribe una declaración de similitud:

Solución

\(\angle A = \angle CDE\)porque son ángulos correspondientes de líneas paralelas. \(\angle C = \angle C\)por identidad. Por lo tanto\(\triangle ABC \sim \triangle DEC\) por\(AA = AA\).

Respuesta:\(\triangle ABC \sim \triangle DEC\).

Determina qué triángulos son similares y escribe una declaración de similitud:

Solución

\(\angle A=\angle A\)identidad. \(\angle ACB = \angle ADC=90^{\circ}\). Por lo tanto

También\(\angle B = \angle B\), identidad,\(\angle BDC = \angle BCA = 90^{\circ}\). Por lo tanto

Respuesta:\(\triangle ABC \sim \triangle ACD \sim \triangle CBD\).

Triangies similares son importantes debido al siguiente teorema:

Los lados correspondientes de triángulos similares son proporcionales. Esto significa que si\(\triangle ABC \sim \triangle DEF\) entonces

\(\dfrac{AB}{DE} = \dfrac{BC}{EF} = \dfrac{AC}{DF}\).

Es decir, las dos primeras letras de\(\triangle ABC\) son a las dos primeras letras de\(\triangle DEF\) como las dos últimas letras de\(\triangle ABC\) son a las dos últimas letras de\(\triangle DEF\) como la primera y última letras de\(\triangle ABC\) son a la primera y última letras de\(\triangle DEF\).

Antes de intentar probar el Teorema\(\PageIndex{2}\), daremos varios ejemplos de cómo se usa:

Encuentra\(x\):

Solución

\(\angle A = \angle D\)y\(\angle B = \angle E\) así\(\triangle ABC \sim \triangle DEF\). Por teorema\(\PageIndex{2}\),

\(\dfrac{AB}{DE} = \dfrac{BC}{EF} = \dfrac{AC}{DF}\).

Vamos a ignorar\(\dfrac{AB}{DE}\) aquí ya que no sabemos y no tenemos que encontrar\(AB\) ni tampoco\(DE\).

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {\dfrac{BC}{EF}} & = & {\dfrac{AC}{DF}} \\ {\dfrac{8}{x}} & = & {\dfrac{2}{3}} \\ {24} & = & {2x} \\ {12} & = & {x} \end{array}\]

Comprobar:

Respuesta:\(x = 12\).

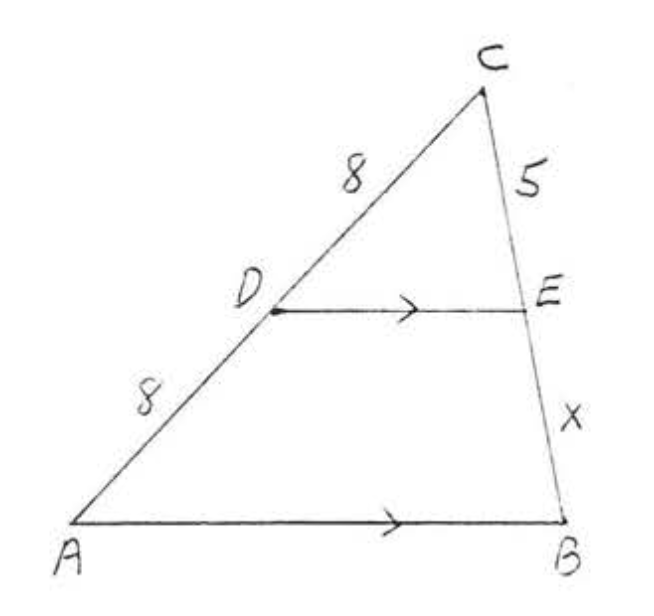

Encuentra\(x\):

Solución

\(\angle A = \angle A, \angle ADE = \angle ABC\), así que\(\triangle ADE \sim \triangle ABC\) por\(AA = AA\).

\(\dfrac{AD}{AB} = \dfrac{DE}{BC} = \dfrac{AE}{AC}\).

Ignoramos\(\dfrac{AD}{AB}\).

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {\dfrac{DE}{BC}} & = & {\dfrac{AE}{AC}} \\ {\dfrac{5}{15}} & = & {\dfrac{10}{10 + x}} \\ {5(10 + x)} & = & {15(10)} \\ {50 + 5x} & = & {150} \\ {5x} & = & {150 - 50} \\ {5x} & = & {100} \\ {x} & = & {20} \end{array}\]

Comprobar:

Respuesta:\(x = 20\).

Encuentra\(x\):

Solución

\(\angle A = \angle CDE\)porque son ángulos correspondientes de líneas paralelas. \(\angle C = \angle C\)por identidad. Por lo tanto\(\triangle ABC \sim \triangle DEC\) por\(AA = AA\).

\(\dfrac{AB}{DE} = \dfrac{BC}{EC} = \dfrac{AC}{DC}\)

Ignoramos\(\dfrac{BC}{EC}\):

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {\dfrac{AB}{DE}} & = & {\dfrac{AC}{DC}} \\ {\dfrac{x + 5}{4}} & = & {\dfrac{x + 3}{3}} \\ {(x + 5)(3)} & = & {(4)(x + 3)} \\ {3x + 15} & = & {4x + 12} \\ {15 - 12} & = & {4x - 3x} \\ {3} & = & {x} \end{array}\]

Comprobar:

Respuesta:\(x = 3\).

Encuentra\(x\):

Solución

\(\angle A = \angle A\),\(\angle ACB = \angle ADC = 90^{\circ}\),\(\triangle ABC \sim \triangle ACD\).

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {\dfrac{AB}{AC}} & = & {\dfrac{AC}{AD}} \\ {\dfrac{x + 12}{8}} & = & {\dfrac{8}{x}} \\ {(x + 12)(x)} & = & {(8)(8)} \\ {x^2 + 12x} & = & {64} \\ {x^2 + 12x - 64} & = & {0} \\ {(x - 4)(x + 16)} & = & {0} \\ {x = 4\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ x} & = & {-16} \end{array}\]

Rechazamos la respuesta\(x = -16\) porque\(AD = x\) no puede ser negativa.

Comprobar,\(x = 4\)

Respuesta:\(x = 4\).

Un árbol proyecta una sombra de 12 pies de largo al mismo tiempo que un hombre de 6 pies proyecta una sombra de 4 pies de largo. ¿Cuál es la altura del árbol?

Solución

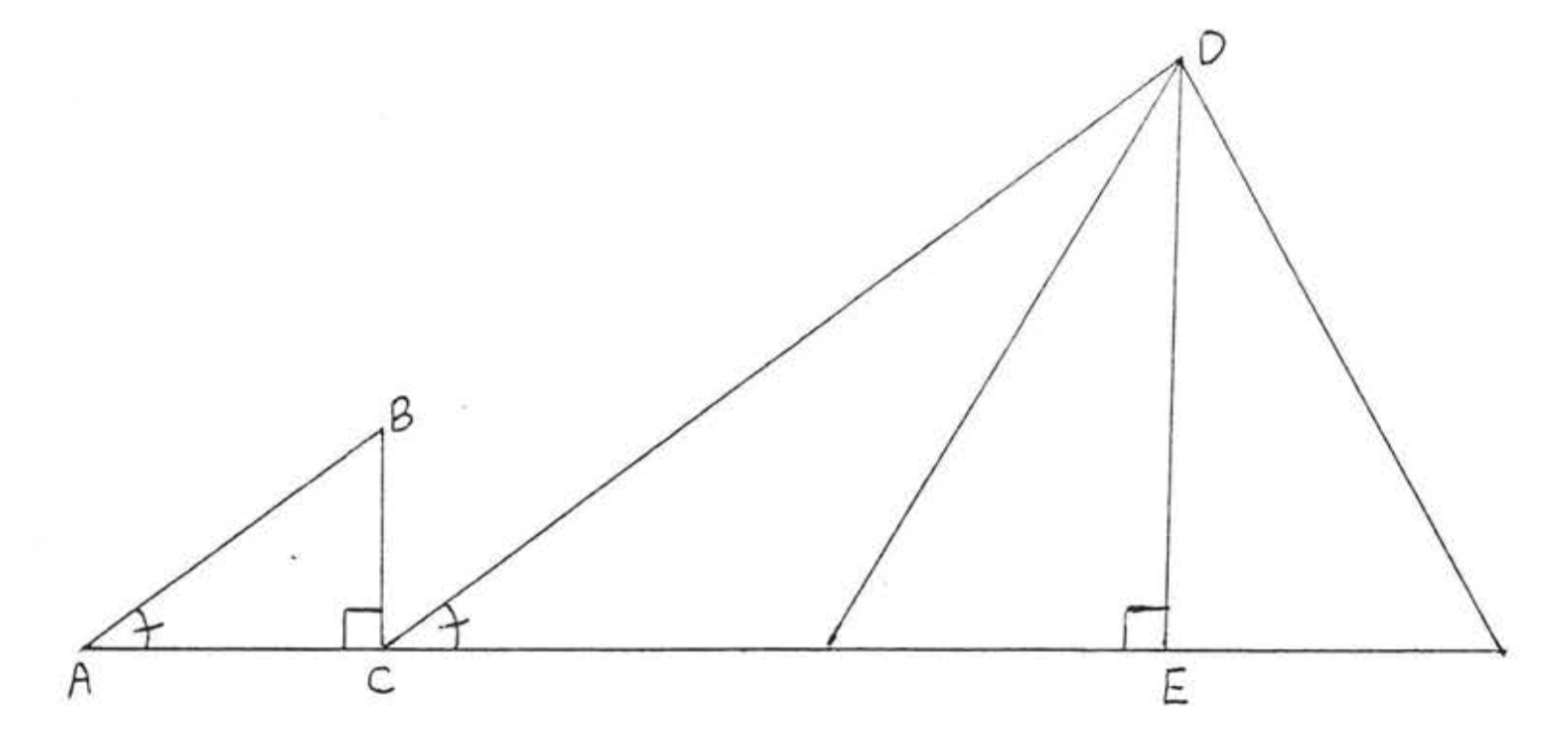

En el diagrama\(AB\) y\(DE\) se encuentran rayos paralelos del sol. Por lo tanto\(\angle A = \angle D\) porque son ángulos correspondientes de líneas paralelas con respecto a la transversal\(AF\). Ya que también\(\angle C = \angle F = 90^{\circ}\), tenemos\(\triangle ABC \sim \triangle DEF\) por\(AA = AA\).

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {\dfrac{AC}{DF}} & = & {\dfrac{BC}{EF}} \\ {\dfrac{4}{12}} & = & {\dfrac{6}{x}} \\ {4x} & = & {72} \\ {x} & = & {18} \end{array}\]

Respuesta:\(x = 18\) pies.

Prueba de teorema\(\PageIndex{2}\) ("The corresponding sides of similar triangles are proportional"):

Ilustramos la prueba usando los triángulos de Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{4}\) (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). The proof for other similar triangles follows the same pattern. Here we will prove that \(x = 12\) so that \(\dfrac{2}{3} = \dfrac{8}{x}\).

Primero dibuje líneas paralelas a los lados de\(\triangle ABC\) y\(\triangle DEF\) como se muestra en la Figura, los\(\PageIndex{4}\). The corresponding ángulos de estas líneas paralelas son iguales y cada uno de los paralelogramos con un lado igual a 1 tiene su lado opuesto igual a 1 también, Por lo tanto todos los triángulos pequeños con un lado igual a 1 son congruente por\(AAS = AAS\). Los lados correspondientes de estos triángulos forman el lado\(BC = 8\) de\(\triangle ABC\) (ver Figura\(\PageIndex{5}\)). Therefore each of these sides must equal 4 and \(x = EF = 4 + 4 + 4 = 12\) (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)).

(Nota al instructor: Esta prueba se puede llevar a cabo siempre que las longitudes de los lados de los triángulos sean números racionales. Sin embargo, dado que los números irracionales pueden aproximarse tan estrechamente como sea necesario por los racionales, la prueba también se extiende a ese caso).

Thales (c. 600 a.C.) utilizó la proporcionalidad de lados de triángulos similares para medir las alturas de las pirámides en Egipto. Su método era muy parecido al que usamos en Ejemplo\(\PageIndex{8}\) to measure the height of trees.

En la Figura\(\PageIndex{7}\), \(DE\) represent the height of the pyramid and \(CE\) is the length of its shadow. \(BC\) represents a vertical stick and \(AC\) is the length of its shadow. We have \(\triangle ABC \sim \triangle CDE\). Thales was able to measure directly the lengths \(AC, BC\), and \(CE\). Substituting these values in the proportion \(\dfrac{BC}{DE} = \dfrac{AC}{CE}\), he was able to find the height \(DE\).

Problemas

1 - 6. Determina qué triángulos son similares y escribe la declaración de similitud:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7 - 22. Para cada una de las siguientes

(1) escribir la declaración de similitud

(2) escribir la proporción entre los lados correspondientes

(3) resolver para\(x\) o\(x\) y\(y\).

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23. Un asta de bandera proyecta una sombra de 80 pies de largo al mismo tiempo que un niño de 5 pies proyecta una sombra de 4 pies de largo. ¿Qué tan alto es el asta de la bandera?

24. Encuentra el ancho\(AB\) del río: