2.5.2: Conversión entre Grados y Radianes

- Page ID

- 107681

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Convertir entre radianes y grados.

La mayoría de las personas están familiarizadas con medir ángulos en grados. Es fácil imaginarse ángulos como\(30^{\circ} \),\(45^{\circ} \) o\(90^{\circ}\) y el hecho de que\(360^{\circ} \) conforma todo un círculo. Hace más de 2000 años los babilonios utilizaron un sistema de números base 60 y dividieron un círculo en 360 partes iguales. Esto se convirtió en el estándar y es como la mayoría de la gente piensa de los ángulos hoy en día.

No obstante, hay muchas unidades con las que medir ángulos. Por ejemplo, el gradián se inventó junto con el sistema métrico y divide un círculo en 400 partes iguales. Los tamaños de estas diferentes unidades son muy arbitrarios.

Un radián es una unidad de ángulos de medición que se basa en las propiedades de los círculos. Esto lo hace más significativo que los gradientes o grados. ¿Cuántos radianes forman un círculo?

Radianes y Grados

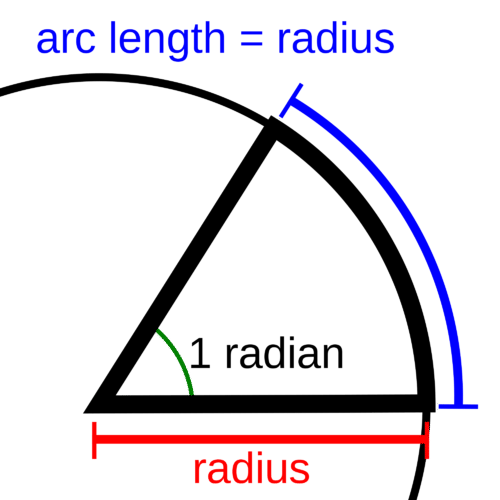

Un radián se define como el ángulo central donde la longitud del arco subtendido es la misma longitud que el radio.

Otra forma de pensar sobre los radianes es a través de la circunferencia de un círculo. La circunferencia de un círculo con radio\(r\) es\(2\pi r\). Un poco más de seis radios (exactamente\(2\pi \) radios) se extenderían alrededor de cualquier círculo.

Para definir un radián en términos de grados, equiparar un círculo medido en grados a un círculo medido en radianes.

\(360 \text{ degrees}=2\pi \text{ radians}\), entonces\(\dfrac{180}{\pi} \text{ degrees}=1 \text{ radian}\)

Alternativamente;\(360 \text{degrees}=2\pi \) radianes, entonces 1 grado=\(\dfrac{\pi}{180}\) radianes

El factor de conversión para convertir grados a radianes es:\(\dfrac{\pi}{180^{\circ}}\)

El factor de conversión para convertir radianes a grados es:\(\dfrac{180^{\circ} }{\pi}\)

Si un ángulo no tiene unidades, se supone que está en radianes.

Si fueras a\(150^{\circ}\) convertir en radianes, te multiplicarías\(150^{\circ} \) por el factor de conversión correcto. Usted obtendría:

\(150^{\circ} \cdot \dfrac{\pi}{180^{\circ}} =\dfrac{15\pi }{18}=\dfrac{5\pi }{6} \text{ radians}\)

Puedes verificar tu trabajo asegurándote de que las unidades de grado aparezcan tanto en el numerador como en el denominador.

Si fueras a convertir\(\dfrac{\pi }{6}\) radianes en grados, multiplicarías\ pi 6 por el factor de conversión correcto. Usted obtendría \(\dfrac{\pi }{6}\cdot \dfrac{180^{\circ} }{\pi }=\dfrac{180^{\circ} }{6}=30^{\circ}\)

Aviso\ pi aparece tanto en el numerador como en el denominador y\ pi\ pi =1.

Antes, te preguntaron cuántos radianes forman un círculo.

Solución

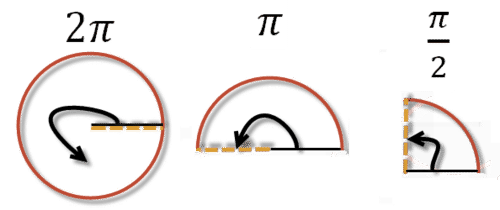

Exactamente\(2\pi \) radianes describen un arco circular. Esto se debe a que los\(2\pi\) radios se envuelven alrededor de la circunferencia de cualquier círculo.

Convertir\((6\pi )^{\circ} \) en radianes.

Solución

No se deje engañar sólo porque esto tiene\(\pi \). Este número es sobre\(19^{\circ}\).

\((6\pi )^{\circ} \cdot \dfrac{\pi}{180^{\circ} }=\dfrac{6\pi^2}{180}=\dfrac{\pi^2}{3}\)

Es muy inusual tener alguna vez un\(\dfrac{\pi}{2}\) término, pero puede suceder.

Convertir\(\dfrac{5\pi }{6}\) en grados.

Solución

\(\dfrac{5\pi }{6} \cdot \dfrac{180^{\circ} }{\pi }=\dfrac{5\cdot 30^{\circ} }{1}=150^{\circ}\)

Convertir\(210^{\circ} \) en radianes.

Solución

\(210^{\circ} \cdot \dfrac{\pi}{180^{\circ} }=\dfrac{7\cdot 30\cdot \pi }{6\cdot 30}=\dfrac{7 \pi}{6}\)

Dibuja un\(\dfrac{\pi}{2}\) ángulo dibujando primero un\(2\pi\) ángulo, reducirlo a la mitad y reducir a la mitad el resultado. Recordemos eso\(\dfrac{\pi}{2}=90^{\circ} \).

Solución

Revisar

Encuentra la medida de radianes de cada ángulo.

1. \(120^{\circ}\)

2. \(300^{\circ}\)

3. \(90^{\circ}\)

4. \(330^{\circ}\)

5. \(270^{\circ}\)

6. \(45^{\circ}\)

7. \((5\pi )^{\circ}\)

Encuentra la medida de grado de cada ángulo.

8. \(\dfrac{7 \pi}{6}\)

9. \(\dfrac{5 \pi}{4}\)

10. \(\dfrac{3 \pi}{2}\)

11. \(\dfrac{5\pi }{3}\)

12. \(\pi\)

13. \(\dfrac{\pi }{6}\)

14. \(3\)

15. Explica por qué si te dan un ángulo en grados y lo\(\dfrac{\pi}{180}\) multiplicas por obtendrás el mismo ángulo en radianes.

Reseña (Respuestas)

Para ver las respuestas de Revisar, abra este archivo PDF y busque la sección 4.1.

El vocabulario

| Término | Definición |

|---|---|

| arco subtendido | Un arco subtendido es la parte del círculo entre los dos rayos que forman el ángulo central. |

Recursos adicionales

Video: Conversiones de radianes y grados - Visión general

Práctica: Conversión entre Grados y Radianes