2.5: Triángulos isósceles

- Page ID

- 114628

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

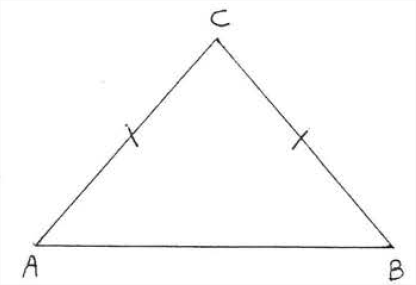

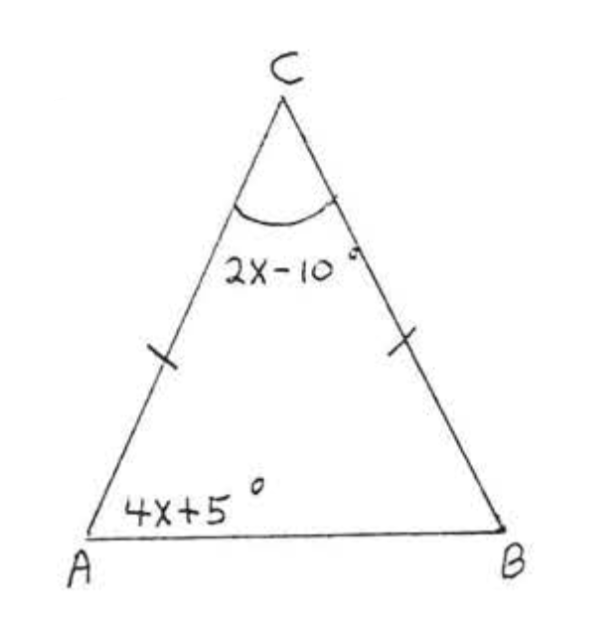

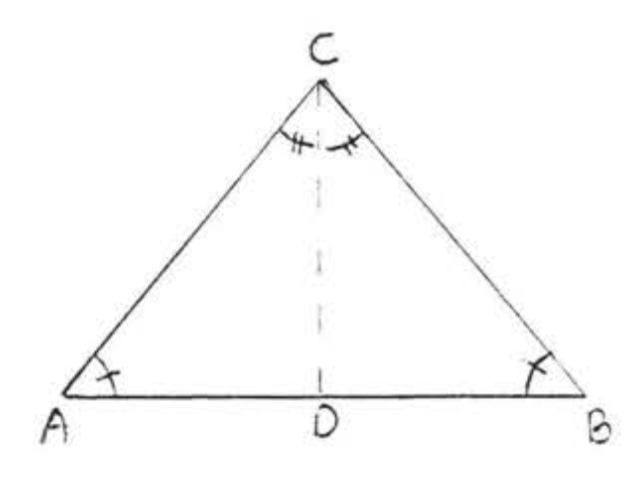

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)En la Sección 1.6, definimos un triángulo para ser isósceles si dos de sus lados son iguales. La figura\(\PageIndex{1}\) muestra un triángulo isósceles\(\triangle ABC\) con\(AC=BC\). En\(\triangle ABC\) decimos que\(\angle A\) es lado opuesto\(BC\) y\(\angle B\) es lado opuesto\(AC\).

El dato más importante sobre los triángulos isósceles es el siguiente:

Si dos lados de un triángulo son iguales los ángulos opuestos a estos lados son iguales.

Teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\) significa que si\(AC = BC\) en\(\triangle ABC\) entonces\(\angle A = \angle B\).

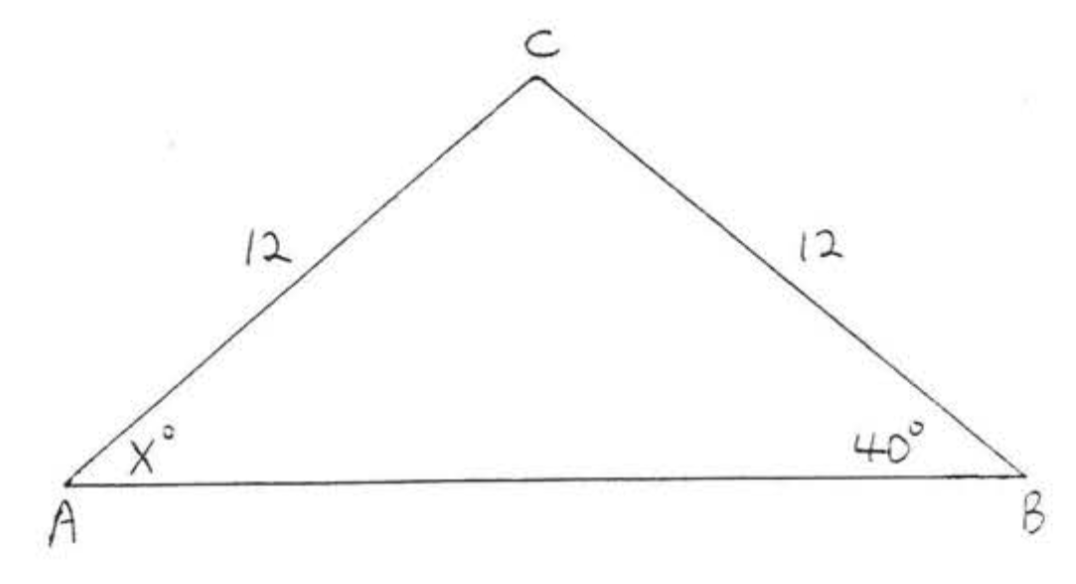

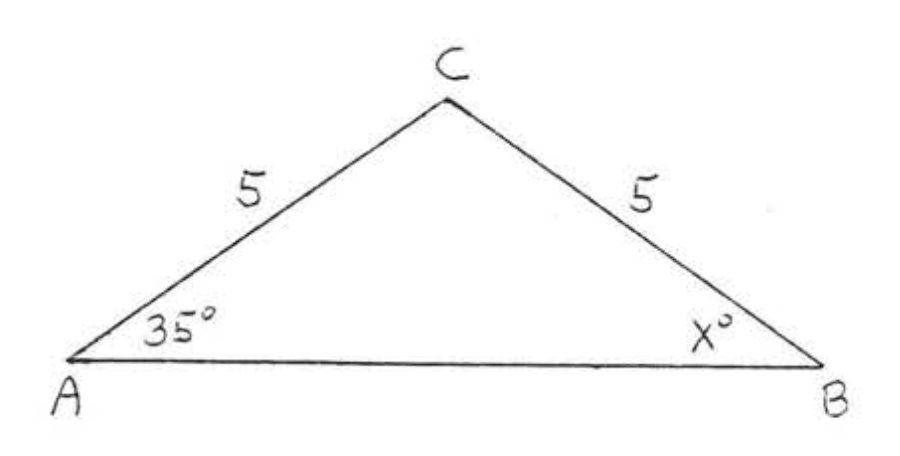

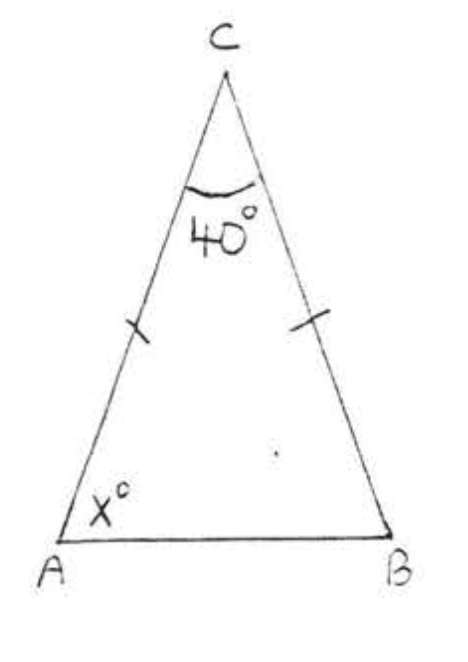

Encuentra\(x\):

Solución

\(AC = BC\)así\(\angle A = \angle B\). Por lo tanto,\(x = 40\).

Respuesta:\(x = 40\).

En\(\triangle ABC\) si\(AC = BC\) entonces lado\(AB\) se llama la base del triángulo y\(\angle A\) y\(\angle B\) se llaman los ángulos base. Por lo tanto, el Teorema a veces\(\PageIndex{1}\) se afirma de la siguiente manera: “Los ángulos de base de un triángulo isósceles son iguales”,

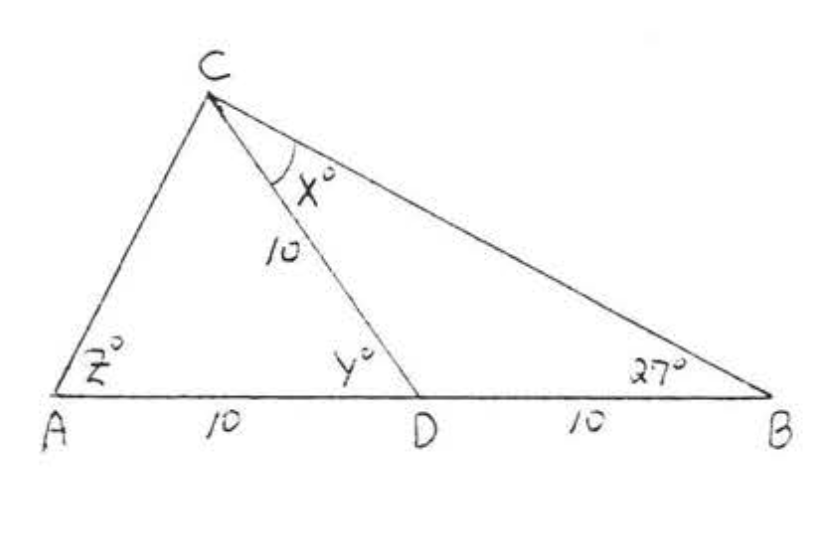

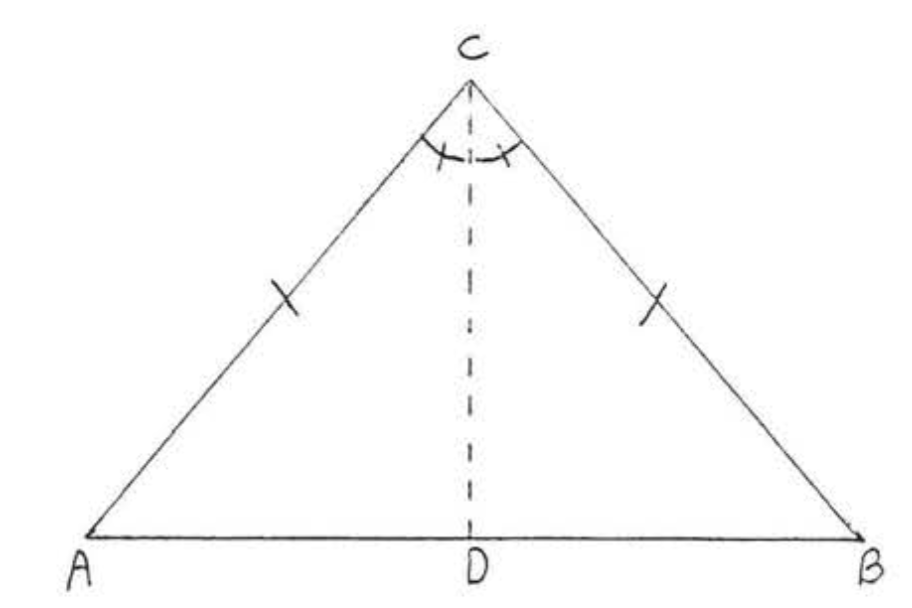

Prueba de Teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\): Dibujar\(CD\), el ángulo bisectriz de\(\angle ACB\) (Figura\(\PageIndex{2}\)). El resto de la prueba se presentará en forma de doble columna. Nosotros hemos dado eso\(AC = BC\) y\(\angle ACD = \angle BCD\). Debemos probarlo\(\angle A = \angle B\).

| Declaraciones | Razones |

|---|---|

| 1. \(AC = BC\). | 1. Dado,\(\triangle ABC\) es isósceles. |

| 2. \(\angle ACD = \angle BCD\). | 2. Dado,\(CD\) es el ángulo bisectriz de\(\angle ACB\). |

| 3. \(CD = CD\). | 3. Identidad. |

| 4. \(\triangle ACD \cong \triangle BCD\). | 4. \(SAS = SAS\):\(AC, \angle C, CD\) de\(\triangle ACD = BC\),\(\angle C, CD\) de\(\triangle BCD\). |

| 5. \(\angle A = \angle B\). | 5. Los ángulos correspondientes de los triángulos congruentes son iguales. |

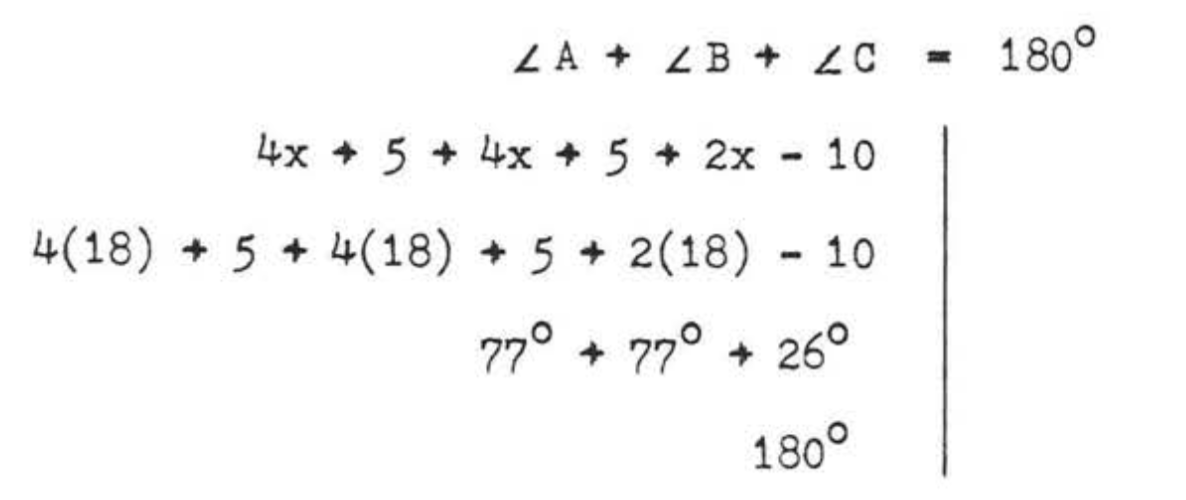

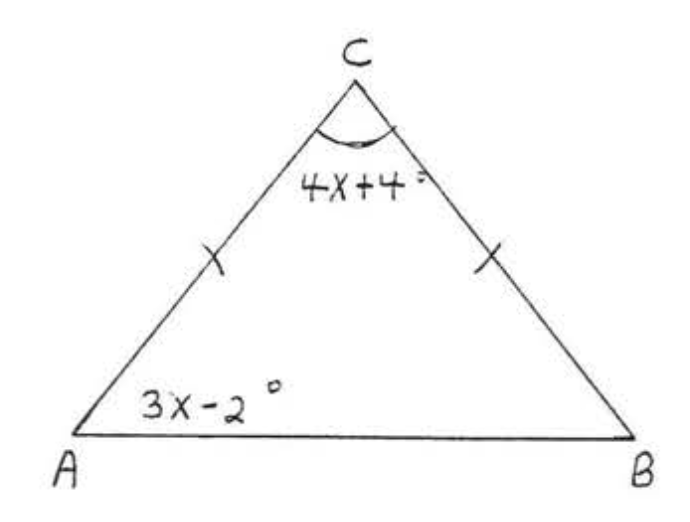

Encuentra\(x, \angle A, \angle B\) y\(\angle C\):

Solución

\(\angle B = \angle A = 4x + 5^{\circ}\)por Teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\). We have

\[\begin{array} {rcl} {\angle A + \angle B + \angle C} & = & {180^{\circ}} \\ {4x + 5 + 4x + 5 + 2x - 10} & = & {180} \\ {10x} & = & {180} \\ {x} & = & {18} \end{array}\]

\(\angle A = \angle B = 4x + 5^{\circ} = 4(18) + 5^{\circ} = 72 + 5^{\circ} = 77^{\circ}\).

\(\angle C = 2x - 10^{\circ} = 2(18) - 10^{\circ} = 36 - 10^{\circ} = 26^{\circ}\).

Cheque

Contestar

\(x = 18\),\(\angle A = 77^{\circ}\),\(\angle B = 77^{\circ}\),\(\angle C = 26^{\circ}\).

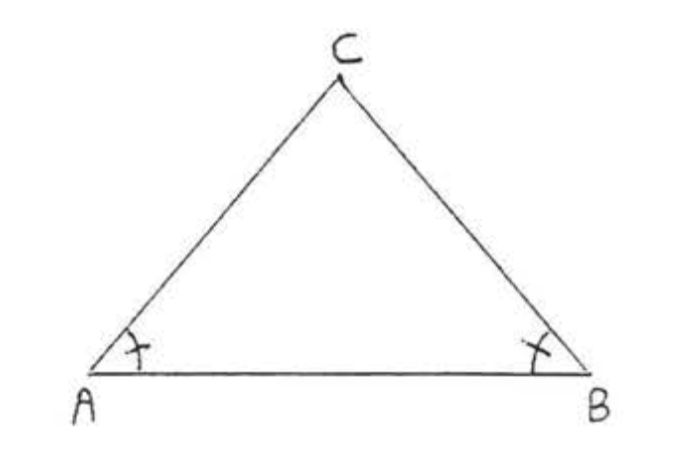

En Teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\) asumimos\(AC = BC\) y probamos\(\angle A = \angle B\). Ahora vamos a asumir\(\angle A = \angle B\) y probar\(AC = BC\). '1icuando se intercambian la suposición y la conclusión de una declaración, el resultado se llama el inverso de la declaración original.

Si dos ángulos de un triángulo son iguales los lados opuestos estos ángulos son iguales.

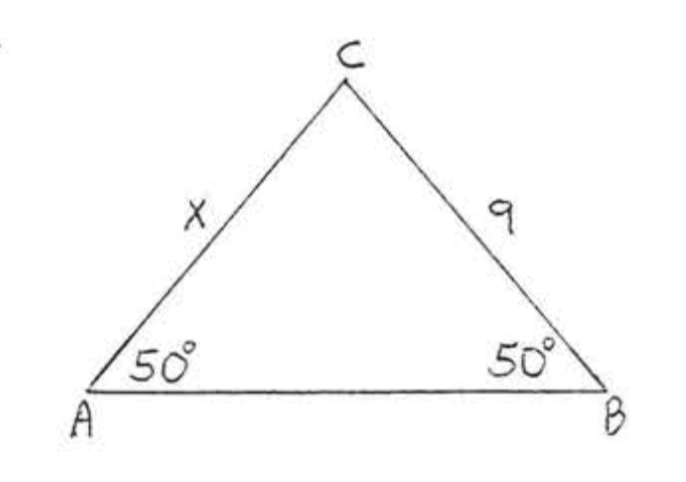

Si Figura 4, si\(\angle A = \angle B\) entonces\(AC = BC\).

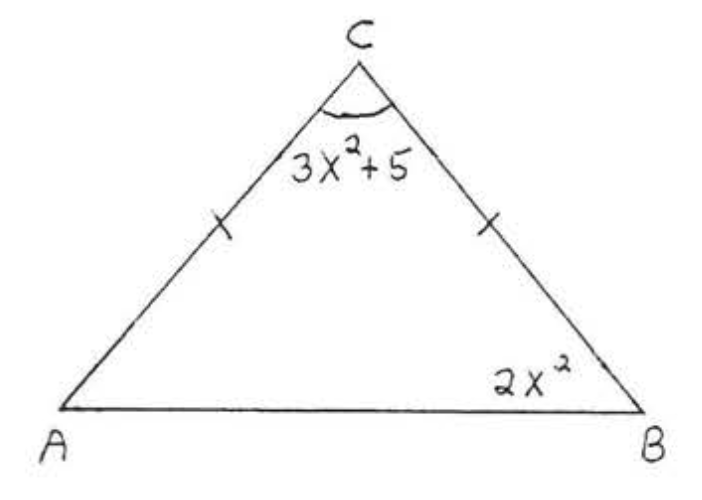

Encuentra\(x\)

Solución

\(\angle A = \angle B\)so\(x = AC = BC = 9\) por teorema\(\PageIndex{2}\).

Contestar

\(x = 9\).

Prueba de teorema\(\PageIndex{2}\): Draw \(CD\) the angle bisector of \(\angle ACB\) (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)). We have \(\angle ACD = \angle BCD\) and \(\angle A = \angle B\). We must prove \(AC = BC\).

| Declaraciones | Razones |

|---|---|

| 1. \(\angle A = \angle B\). | 1. Dado. |

| 2. \(\angle ACD = \angle BCD\). | 2. Dado. |

| 3. \(CD = CD\). | 3. Identidad. |

| 4. \(\triangle ACD \cong \triangle BCD\). | 4. \(AAS = AAS\):\(\angle A, \angle C, CD\) de\(\triangle ACD = \angle B\),\(\angle C\),\(CD\) de\(triangle BCD\). |

| 5. \(AC = BC\). | 5. Los lados correspondientes de los triángulos congruentes son iguales |

Los dos teoremas siguientes son corolarios (consecuencias inmediatas) de los dos teoremas anteriores:

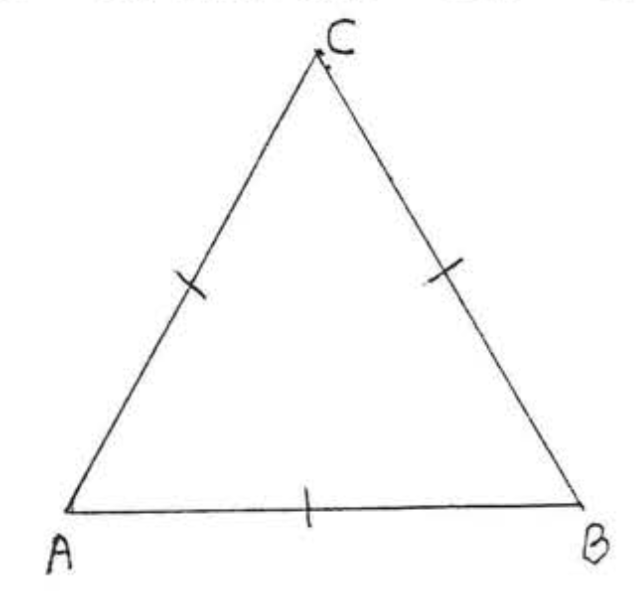

Un triángulo equilátero es equiangular.

En la Figura\(\PageIndex{7}\), if \(AB = AC = BC\) then \(\angle A = \angle B = \angle C\).

- Prueba

-

\(AC = BC\)so por teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\) \(\angle B = \angle C\). Therefore \(\angle A = \angle B = \angle C\).

Dado que la suma del ángulo es\(180^{\circ}\) we must have in fact that \(\angle A = \angle B = \angle C = 60^{\circ}\).

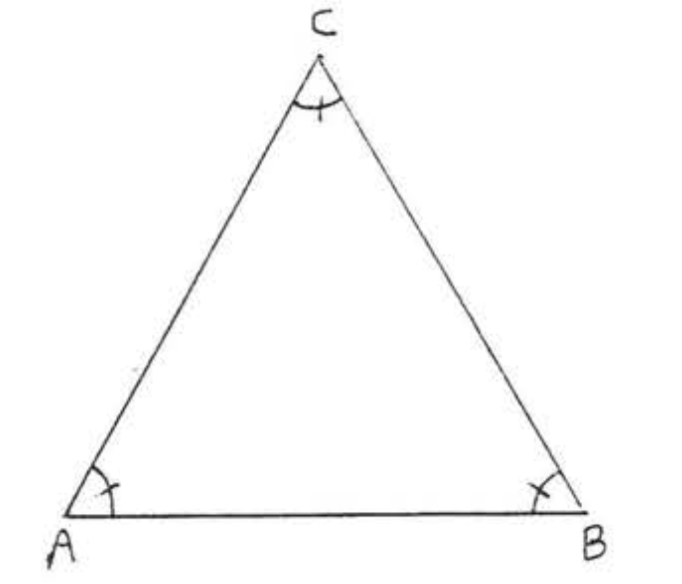

Un triángulo equiangular es equilátero.

En la Figura\(\PageIndex{8}\), if \(\angle A = \angle B = \angle C\) then \(AB = AC = BC\).

- Prueba

-

\(\angle A = \angle B\)so por teorema\(\PageIndex{2}\), \(AC = BC\), \(\angle B = \angle C\) by Theorem \(\PageIndex{2}\), \(AB = AC\). Therefore \(AB = AC = BC\).

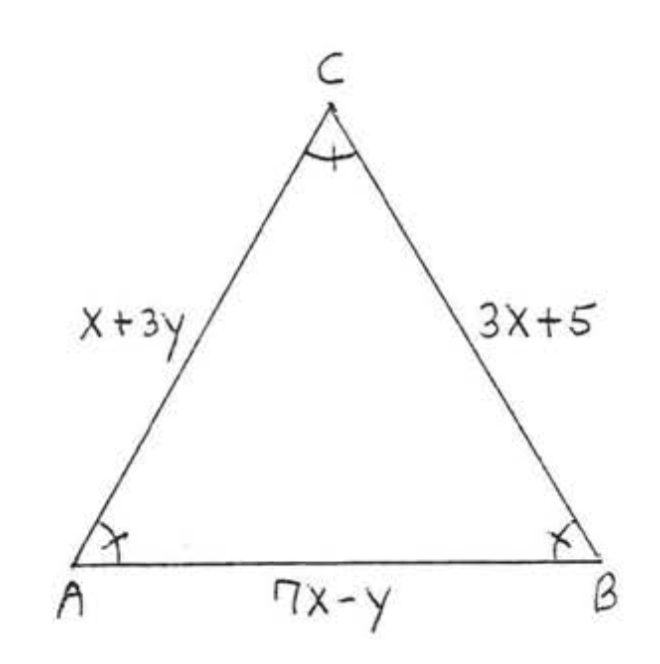

Buscar\(x\),\(y\) y\(AC\):

Solución

\(\triangle ABC\)es equiangular y así por teorema\(\PageIndex{4}\) is equilateral.

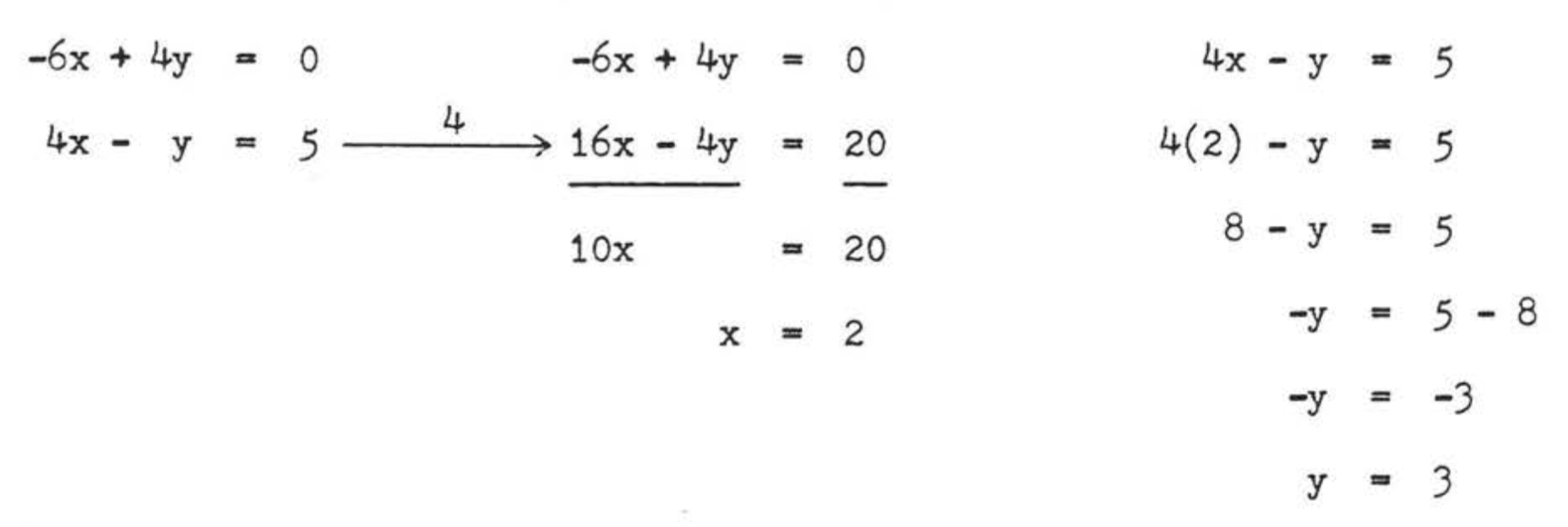

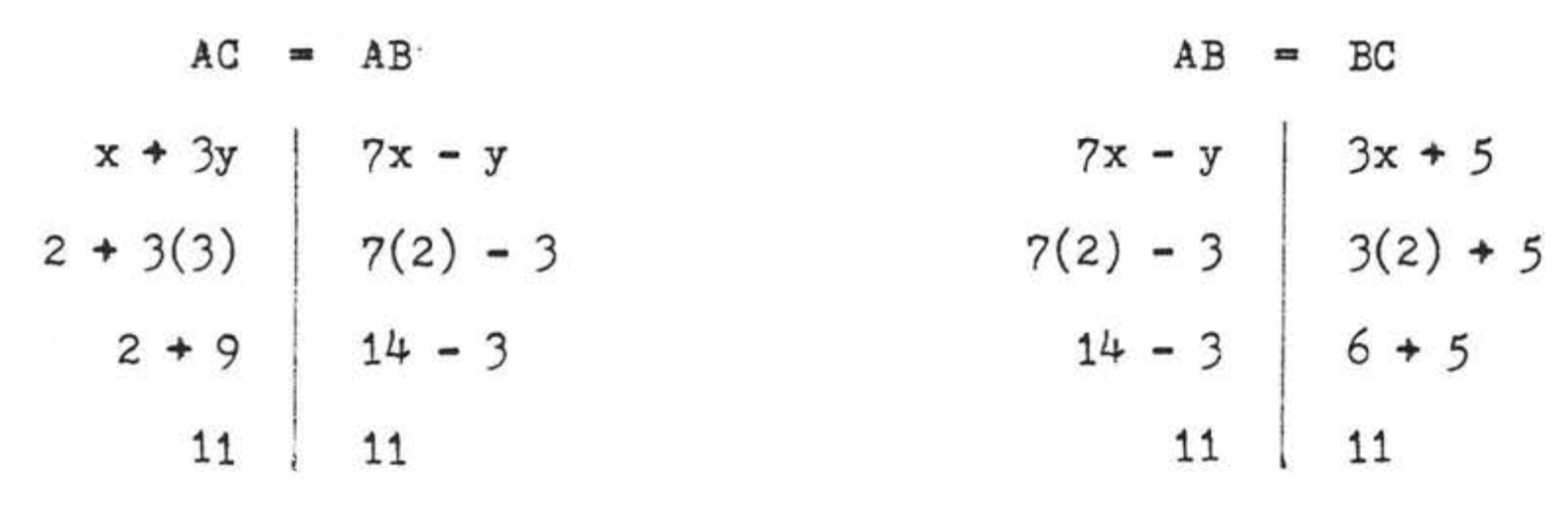

Por lo tanto\(\begin{array} {rcl} {AC} & = & {AB} \\ {x + 3y} & = & {7x - y} \\ {x - 7x + 3y + y} & = & {0} \\ {-6x + 4y} & = & {0} \end{array}\) and \(\begin{array} {rcl} {AB} & = & {BC} \\ {7x - y} & = & {3x + 5} \\ {7x - 3xy - y} & = & {5} \\ {4x - y} & = & {5} \end{array}\)

Tenemos un sistema de dos ecuaciones en dos incógnitas para resolver:

Comprobar:

Respuesta:\(x = 2\),\(y = 3\),\(AC = 11\).

Teorema\(\PageIndex{1}\), el teorema del triángulo isósceles, se cree que primero fue probado por Thales (c. 600 B, C,) - es la Proposición 5 en los Elementos de Euclides. La prueba de Euclides es más complicada que la nuestra porque no quiso asumir la existencia de una bisectriz angular, la prueba de Euclides va de la siguiente manera:

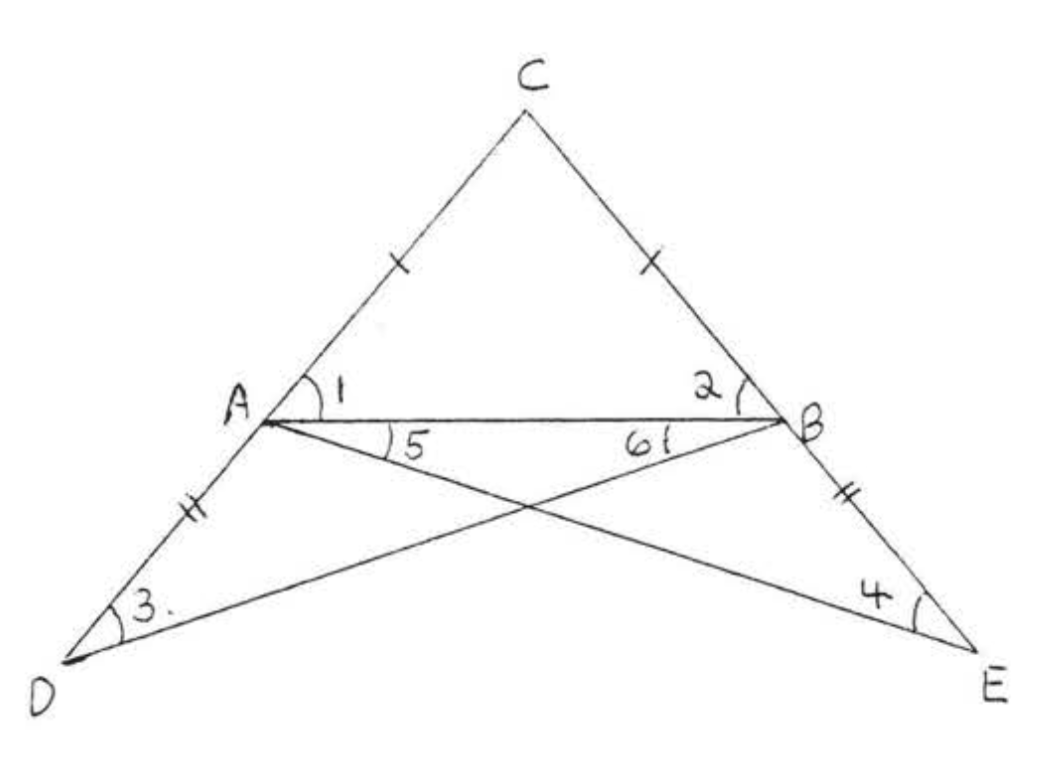

Dado\(\triangle ABC\) con\(AC = BC\) (como en la Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\) at the beginning of this section), extend \(CA\) to \(D\) and \(CB\) to \(E\) so that \(AD = BE\) (Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)). Then \(\triangle DCB \cong \triangle ECA\) by \(SAS = SAS\). The corresponding sides and angles of the congruent triangles are equal, so \(DB = EA\), \(\angle 3 = \angle 4\) and \(\angle 1 + \angle 5 = \angle 2 + \angle 6\). Now \(\triangle ADB \cong \triangle BEA\) by \(SAS = SAS\). This gives \(\angle 5 = \angle 6\) and finally \(\angle 1 = \angle 2\).

Esta complicada prueba disuadió a muchos estudiantes de seguir estudiando geometría durante el largo período en que los Elementos era el texto estándar, La figura\(\PageIndex{9}\) se asemeja a un puente que en la Edad Media se conoció como el “puente de los tontos”, Esto supuestamente se debió a que un tonto podía no espero cruzar este puente y abandonaría la geometría en este punto.

Problemas

Para cada uno de los siguientes estados el (los) teorema (s) utilizado (s) para obtener su respuesta.

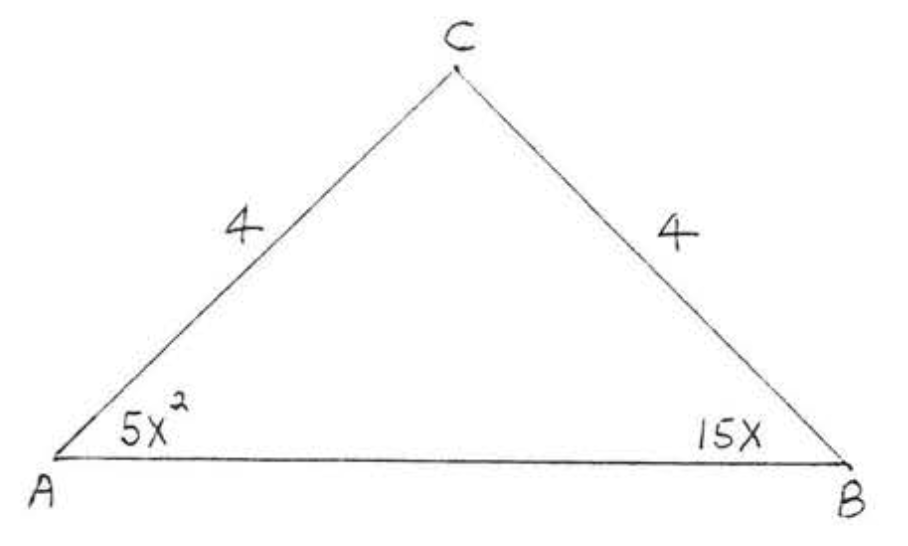

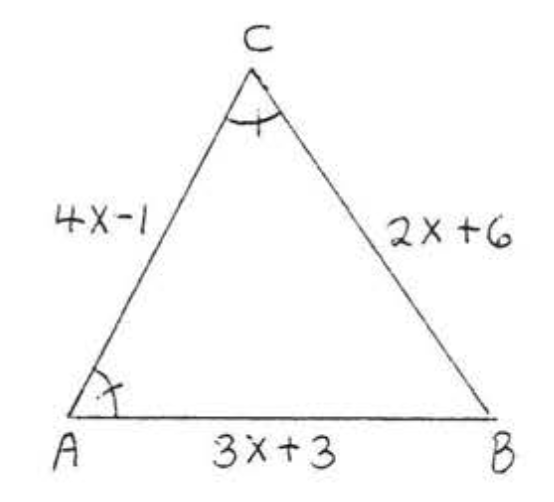

1. Encuentra\(x\):

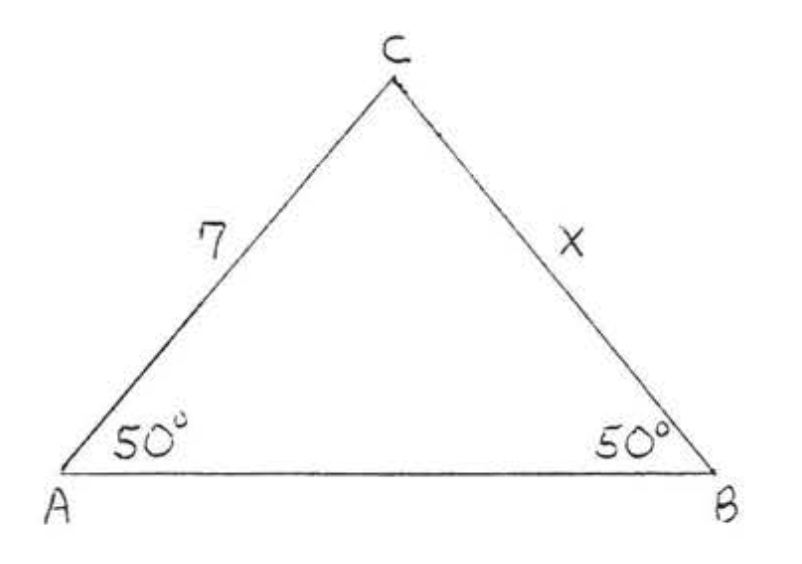

2. Buscar\(x\),\(\angle A\), y\(\angle B\):

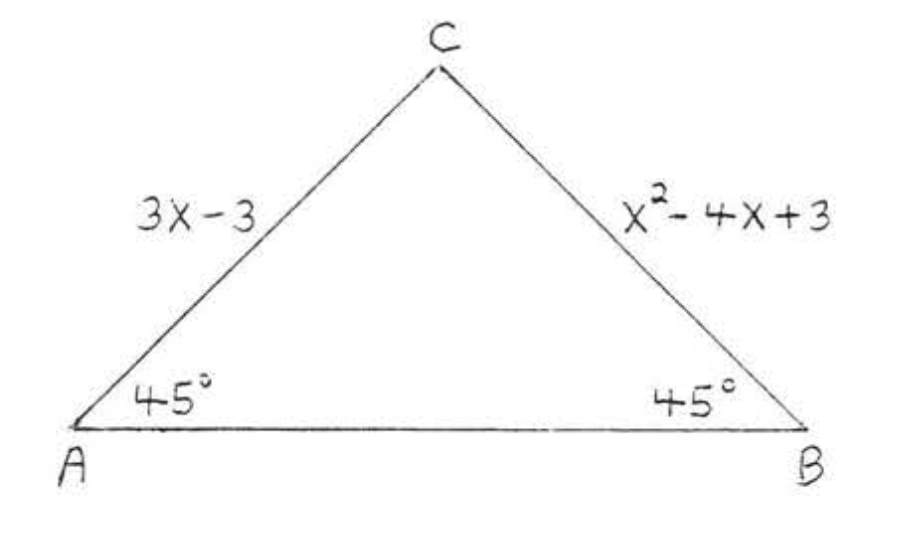

3. Encuentra\(x\):

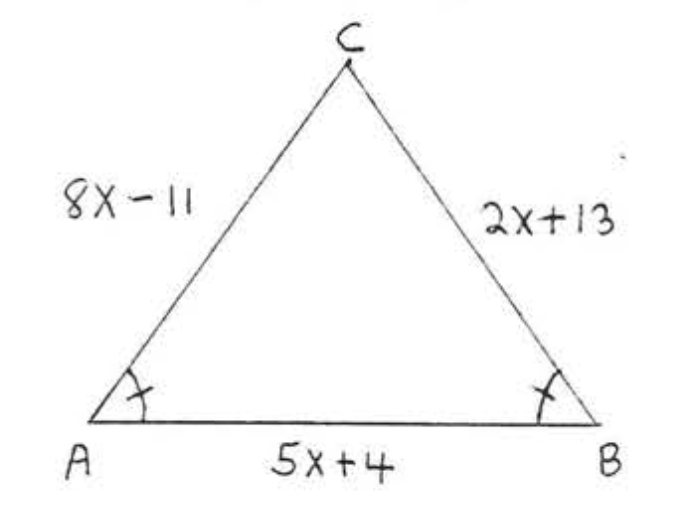

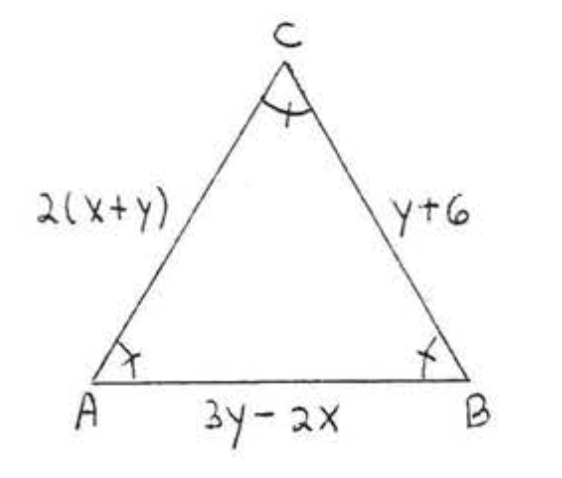

4. Buscar\(x\),\(AC\), y\(BC\):

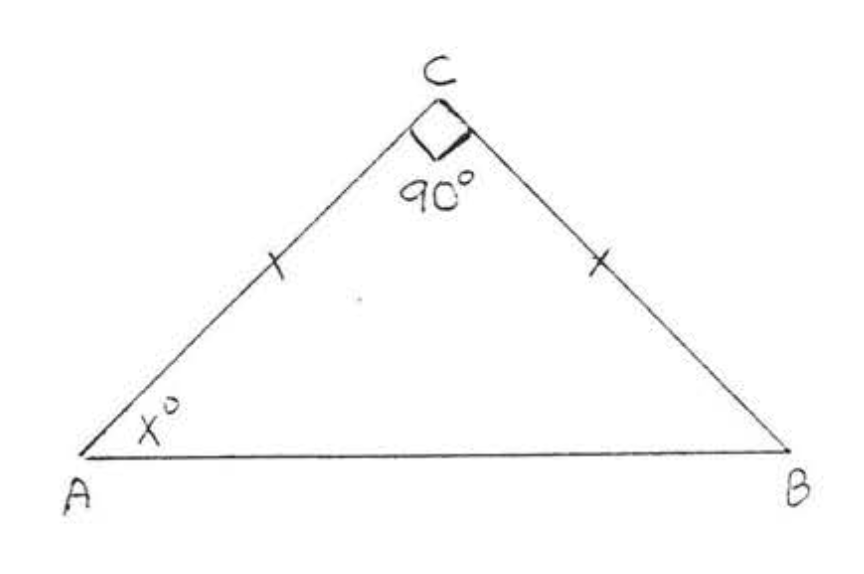

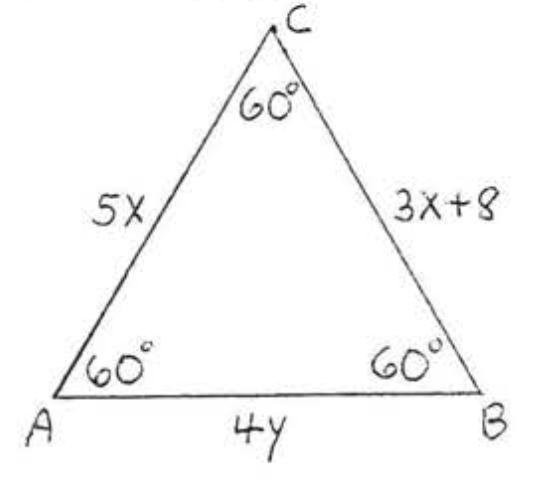

5. Encuentra\(x\):

6. Encuentra\(x\):

7. Buscar\(x, \angle A, \angle B\), y\(\angle C\):

8. Buscar\(x, \angle A, \angle B\), y\(\angle C\):

9. Buscar\(x, AB, AC\), y\(BC\):

10. Buscar\(x, AB, AC\), y\(BC\):

11. Buscar\(x, y\), y\(AC\):

12. Buscar\(x, y\), y\(AC\):

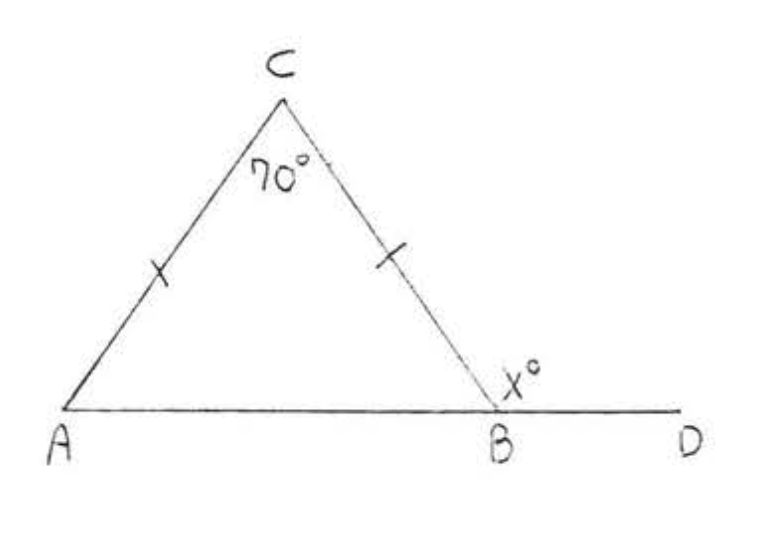

13. Encuentra\(x\):

14. Buscar\(x, y\), y\(z\):