1.23: Área de Polígonos Regulares

- Page ID

- 110938

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Puede usar una calculadora a lo largo de este módulo.

El edificio del Pentágono abarca\(28.7\) acres (\(116,000\text{ m}^2\)), e incluye\(5.1\) acres adicionales (\(21,000\text{ m}^2\)) como patio central. [1] Un pentágono es un ejemplo de un polígono regular.

Un polígono regular tiene todos los lados de igual longitud y todos los ángulos de igual medida. Debido a esta simetría, un círculo puede ser inscrito, dibujado dentro del polígono tocando cada lado en un punto, o circunscrito, dibujado fuera del polígono que cruza cada vértice. Nos centraremos primero en el círculo inscrito.

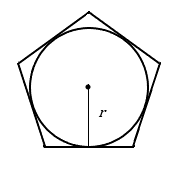

Llamemos minúscula al radio del círculo inscrito\(r\); esta es la distancia desde el centro del polígono perpendicular a uno de los lados. [2]

Área de un Polígono Regular (con un radio dibujado al centro de un lado) [3]

Para un polígono regular con\(n\) lados de longitud\(s\) y radio inscrito (interior)\(r\),

\[A=nsr\div2 \nonumber \]

Nota: Esta fórmula se deriva de dividir el polígono en triángulos de\(n\) igual tamaño y combinar las áreas de esos triángulos.

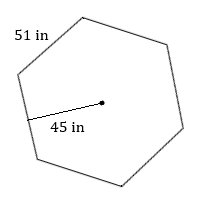

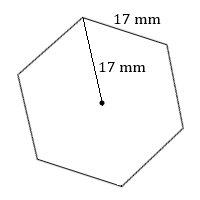

1. Calcular el área de este hexágono regular.

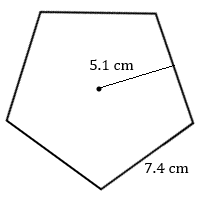

2. Calcular el área de este pentágono regular.

3. Una señal de alto tiene una altura de\(30\) inches, and each edge measures \(12.5\) inches. Find the area of the sign.

- Contestar

-

1. \(6,900\text{ in}^2\)

2. \(94\text{ cm}^2\)

3. \(750\text{ in}^2\)

Bien, pero ¿y si conocemos la distancia del centro a una de las esquinas en lugar de la distancia del centro a un borde? Tendremos que imaginar un círculo circunscrito.

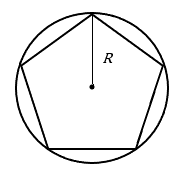

Llamemos capital al radio del círculo circunscrito\(R\); esta es la distancia desde el centro del polígono a uno de los vértices (esquinas).

Área de un Polígono Regular (con un radio dibujado en un vértice) [4]

Para un polígono regular con\(n\) lados de longitud\(s\) y radio circunscrito (exterior)\(R\),

\[A=0.25ns\sqrt{4R^2-s^2} \nonumber \]

o

\[A=ns\sqrt{4R^2-s^2}\div4 \nonumber \]

Nota: Esta fórmula también se deriva de dividir el polígono en triángulos de\(n\) igual tamaño y combinar las áreas de esos triángulos. Esta fórmula incluye una raíz cuadrada porque involucra el teorema de Pitágoras.

4. Calcular el área de este hexágono regular.

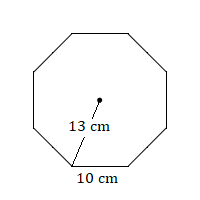

5. Calcular el área de este octágono regular.

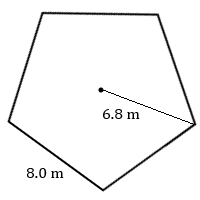

6. Calcular el área de este pentágono regular.

- Contestar

-

4. \(750\text{ mm}^2\)

5. \(480\text{ cm}^2\)

6. \(110\text{ m}^2\)

Como sabéis, una figura compuesta es una figura geométrica que se forma uniendo dos o más figuras geométricas básicas. Veamos una figura compuesta formada por un círculo y un polígono regular.

7. La cabeza hexagonal de un perno encaja perfectamente en una tapa circular con un orificio circular con diámetro interior\(46\text{ mm}\) as shown in this diagram. Opposite sides of the bolt head are \(40\text{ mm}\) apart. Find the total empty area in the hole around the edges of the bolt head.

- Contestar

-

\(280\text{ mm}^2\)(el área del círculo\(\approx1,660\text{ mm}^2\) y el área del hexágono es\(1,380\text{ mm}^2\))

- [1]https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Pentagon

- El radio interior es más comúnmente llamado apotema y etiquetado\(a\), pero estamos tratando de mantener la jerga al mínimo en este libro de texto.

- Esta fórmula se escribe más comúnmente como la mitad del apotema multiplicado por el perímetro\(A=\dfrac{1}{2}ap\):

- Tu autor creó esta fórmula porque cada otra versión de la misma usa trigonometría, que no estamos cubriendo en este libro de texto.