1.3: Funciones trigonométricas

- Page ID

- 116828

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Convertir medidas de ángulo entre grados y radianes.

- Reconocer las definiciones triangulares y circulares de las funciones trigonométricas básicas.

- Escribir las identidades trigonométricas básicas.

- Identificar las gráficas y periodos de las funciones trigonométricas.

- Describir el desplazamiento de una gráfica de seno o coseno a partir de la ecuación de la función.

Las funciones trigonométricas se utilizan para modelar muchos fenómenos, incluyendo las ondas sonoras, las vibraciones de las cuerdas, la corriente eléctrica alterna y el movimiento de los péndulos. De hecho, casi cualquier movimiento repetitivo, o cíclico, puede ser modelado por alguna combinación de funciones trigonométricas. En esta sección, definimos las seis funciones trigonométricas básicas y observamos algunas de las identidades principales que involucran estas funciones.

Medida de radianes

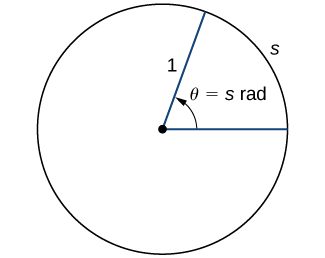

Para utilizar funciones trigonométricas, primero debemos entender cómo medir los ángulos. Aunque podemos usar tanto radianes como grados, los radianes son una medida más natural porque están relacionados directamente con el círculo unitario, un círculo con radio 1. La medida radianes de un ángulo se define de la siguiente manera. Dado un ángulo\(θ\), deja\(s\) ser la longitud del arco correspondiente en el círculo unitario (Figura\(\PageIndex{1}\)). Decimos que el ángulo correspondiente al arco de longitud 1 tiene medida de radianes 1.

Dado que un ángulo de\(360°\) corresponde a la circunferencia de un círculo, o un arco de longitud\(2π\), concluimos que un ángulo con una medida de grado de\(360°\) tiene una medida de radianes de\(2π\). De igual manera, vemos que\(180°\) es equivalente a\(\pi\) radianes. En el cuadro se\(\PageIndex{1}\) muestra la relación entre los valores comunes de grado y radianes.

| Grados | Radianes | Grados | Radianes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 120 | \(2π/3\) |

| 30 | \(π/6\) | 135 | \(3π/4\) |

| 45 | \(π/4\) | 150 | \(5π/6\) |

| 60 | \(π/3\) | 180 | \(π\) |

| 90 | \(π/2\) |

- Express\(225°\) using radians.

- Express\(5π/3\) rad using degrees.

Solución

Utilizar el hecho de que\(180\)° es equivalente a\(\pi\) radianes como factor de conversión (Tabla\(\PageIndex{1}\)):

\[1=\dfrac{π \,\mathrm{rad}}{180°}=\dfrac{180°}{π \,\mathrm{rad}}. \nonumber \]

- \(225°=225°⋅\left(\dfrac{π}{180°}\right)=\left(\dfrac{5π}{4}\right)\) rad

- \(\dfrac{5π}{3}\) rad = \(\dfrac{5π}{3}\)⋅\(\dfrac{180°}{π}\)=\(300\)°

- \(210°\)Exprese usando radianes.

- Express\(11π/6\) rad using degrees.

- Pista

-

\(π\)radianes es igual a 180°

- Contestar

-

- \(7π/6\)

- 330°

Las seis funciones trigonométricas básicas

Las funciones trigonométricas nos permiten usar medidas de ángulo, en radianes o grados, para encontrar las coordenadas de un punto en cualquier círculo, no solo en un círculo unitario, o para encontrar un ángulo dado un punto en un círculo. También definen la relación entre los lados y los ángulos de un triángulo.

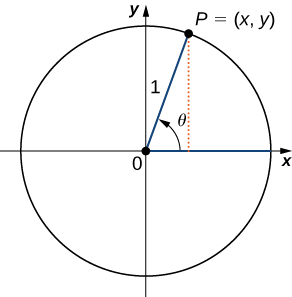

Para definir las funciones trigonométricas, primero considere el círculo unitario centrado en el origen y un punto\(P=(x,y)\) en el círculo unitario. Dejar\(θ\) ser un ángulo con un lado inicial que se encuentra a lo largo del\(x\) eje positivo y con un lado terminal que es el segmento de línea\(OP\). Se dice que un ángulo en esta posición está en posición estándar (Figura\(\PageIndex{2}\)). Luego podemos definir los valores de las seis funciones trigonométricas para\(θ\) en términos de las coordenadas\(x\) y\(y\).

Dejar\(P=(x,y)\) ser un punto en el círculo unitario centrado en el origen\(O\). Let\(θ\) ser un ángulo con un lado inicial a lo largo del\(x\) eje positivo y un lado terminal dado por el segmento de línea\(OP\). Las funciones trigonométricas se definen entonces como

| \(\sin θ=y\) | \(\csc θ=\dfrac{1}{y}\) |

| \(\cos θ=x\) | \(\sec θ=\dfrac{1}{x}\) |

| \(\tan θ=\dfrac{y}{x}\) | \(\cot θ=\dfrac{x}{y}\) |

Si\(x=0, \sec θ\) y\(\tan θ\) son indefinidos. Si\(y=0\), entonces\(\cot θ\) y\(\csc θ\) son indefinidos.

Podemos ver que para un punto\(P=(x,y)\) en un círculo de radio\(r\) con un ángulo correspondiente\(θ\), las coordenadas\(x\) y\(y\) satisfacer

\[\begin{align} \cos θ &=\dfrac{x}{r} \\ x &=r\cos θ \end{align} \nonumber \]

y

\[\begin{align} \sin θ &=\dfrac{y}{r} \\ y &=r\sin θ. \end{align} \nonumber \]

Los valores de las otras funciones trigonométricas se pueden expresar en términos de\(x,y\), y\(r\) (Figura\(\PageIndex{3}\)).

\(\PageIndex{2}\)La tabla muestra los valores de seno y coseno en los ángulos principales en el primer cuadrante. A partir de esta tabla, podemos determinar los valores de seno y coseno en los ángulos correspondientes en los otros cuadrantes. Los valores de las otras funciones trigonométricas se calculan fácilmente a partir de los valores de\(\sin θ\) and \(\cos θ.\)

| \(θ\)θ | \(\sin θ\) | \(\cos θ\) |

|---|---|---|

| \ (θ\) θ” style="text-align:center; ">0 | \ (\ sin θ\)” style="text-align:center; ">0 | \ (\ cos θ\)” style="text-align:center; ">1 |

| \ (θ\) θ” style="text-align:center; ">\(\dfrac{π}{6}\) | \ (\ sin θ\)” style="text-align:center; ">\(\dfrac{1}{2}\) | \ (\ cos θ\)” style="text-align:center; ">\(\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\) |

| \ (θ\) θ” style="text-align:center; ">\(\dfrac{π}{4}\) | \ (\ sin θ\)” style="text-align:center; ">\(\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\) | \ (\ cos θ\)” style="text-align:center; ">\(\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\) |

| \ (θ\) θ” style="text-align:center; ">\(\dfrac{π}{3}\) | \ (\ sin θ\)” style="text-align:center; ">\(\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\) | \ (\ cos θ\)” style="text-align:center; ">\(\dfrac{1}{2}\) |

| \ (θ\) θ” style="text-align:center; ">\(\dfrac{π}{2}\) | \ (\ sin θ\)” style="text-align:center; ">1 | \ (\ cos θ\)” style="text-align:center; ">0 |

Evalúe cada una de las siguientes expresiones.

- \(\sin \left(\dfrac{2π}{3} \right)\)

- \(\cos \left(−\dfrac{5π}{6} \right)\)

- \(\tan \left(\dfrac{15π}{4}\right)\)

Solución:

a) En el círculo unitario, el ángulo\(θ=\dfrac{2π}{3}\) corresponde al punto\(\left(−\dfrac{1}{2},\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)\). Por lo tanto,

\[ \sin \left(\dfrac{2π}{3}\right)=y=\left(\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right). \nonumber \]

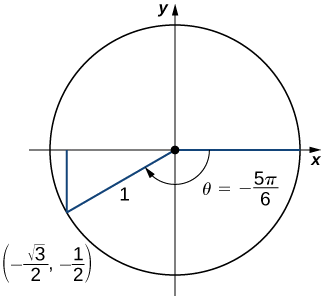

b) Un ángulo\(θ=−\dfrac{5π}{6}\) corresponds to a revolution in the negative direction, as shown. Therefore,

\[\cos \left(−\dfrac{5π}{6}\right)=x=−\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}. \nonumber \]

c) An angle \(θ\)=\(\dfrac{15π}{4}\)=\(2π\)+\(\dfrac{7π}{4}\). Therefore, this angle corresponds to more than one revolution, as shown. Knowing the fact that an angle of \(\dfrac{7π}{4}\) corresponds to the point \((\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2},-\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2})\), we can conclude that

\[\tan \left(\dfrac{15π}{4}\right)=\dfrac{y}{x}=−1. \nonumber \]

Evaluate \(\cos(3π/4)\) and \(\sin(−π/6)\).

- Hint

-

Look at angles on the unit circle.

- Answer

-

\[\cos(3π/4) = −\sqrt{2}/2\nonumber \]

\[ \sin(−π/6) =−1/2 \nonumber \]

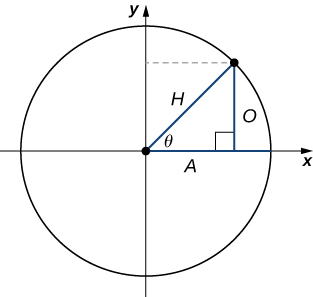

As mentioned earlier, the ratios of the side lengths of a right triangle can be expressed in terms of the trigonometric functions evaluated at either of the acute angles of the triangle. Let \(θ\) be one of the acute angles. Let \(A\) be the length of the adjacent leg, \(O\) be the length of the opposite leg, and \(H\) be the length of the hypotenuse. By inscribing the triangle into a circle of radius \(H\), as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\), we see that \(A,H\), and \(O\) satisfy the following relationships with \(θ\):

| \(\sin θ=\dfrac{O}{H}\) | \(\csc θ=\dfrac{H}{O}\) |

| \(\cos θ=\dfrac{A}{H}\) | \(\sec θ=\dfrac{H}{A}\) |

| \(\tan θ=\dfrac{O}{A}\) | \(\cot θ=\dfrac{A}{O}\) |

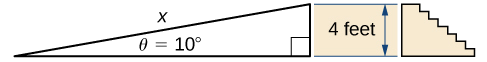

A wooden ramp is to be built with one end on the ground and the other end at the top of a short staircase. If the top of the staircase is \(4\) ft from the ground and the angle between the ground and the ramp is to be \(10\)°, how long does the ramp need to be?

Solution

Let \(x\) denote the length of the ramp. In the following image, we see that \(x\) needs to satisfy the equation \(\sin(10°)=4/x\). Solving this equation for \(x\), we see that \(x=4/\sin(10°)\)≈\(23.035\) ft.

A house painter wants to lean a \(20\)-ft ladder against a house. If the angle between the base of the ladder and the ground is to be \(60\)°, how far from the house should she place the base of the ladder?

- Hint

-

Draw a right triangle with hypotenuse 20.

- Answer

-

10 ft

Trigonometric Identities

A trigonometric identity is an equation involving trigonometric functions that is true for all angles \(θ\) for which the functions are defined. We can use the identities to help us solve or simplify equations. The main trigonometric identities are listed next.

Reciprocal identities

\[\tan θ=\dfrac{\sin θ}{\cos θ} \nonumber \]

\[\cot θ=\dfrac{\cos θ}{\sin θ} \nonumber \]

\[\csc θ=\dfrac{1}{\sin θ} \nonumber \]

\[\sec θ=\dfrac{1}{\cos θ} \nonumber \]

Pythagorean identities

\[\begin{align} \sin^2θ+\cos^2θ &=1 \label{py1} \\[4pt] 1+\tan^2θ &=\sec^2θ \\[4pt] 1+\cot^2θ &=\csc^2θ \end{align} \]

Addition and subtraction formulas

\[\sin(α±β)=\sin α\cos β±\cos α \sin β \nonumber \]

\[\cos(α±β)=\cos α\cos β∓\sin α \sin β \nonumber \]

Double-angle formulas

\[\sin(2θ)=2\sin θ\cos θ \label{double1} \]

\[\begin{align} \cos(2θ) &=2\cos^2θ−1 \\[4pt] &=1−2\sin^2θ \\[4pt] &=\cos^2θ−\sin^2θ \end{align} \nonumber \]

For each of the following equations, use a trigonometric identity to find all solutions.

- \(1+\cos(2θ)=\cos θ\)

- \(\sin(2θ)=\tan θ\)

Solution

a) Using the double-angle formula for \(\cos(2θ)\), we see that \(θ\) is a solution of

\[1+\cos(2θ)=\cos θ \nonumber \]

if and only if

\[1+2\cos^2θ−1=\cos θ, \nonumber \]

which is true if and only if

\[2\cos^2θ−\cos θ=0. \nonumber \]

To solve this equation, it is important to note that we need to factor the left-hand side and not divide both sides of the equation by \(\cos θ\). The problem with dividing by \(\cos θ\) is that it is possible that \(\cos θ\) is zero. In fact, if we did divide both sides of the equation by \(\cos θ\), we would miss some of the solutions of the original equation. Factoring the left-hand side of the equation, we see that \(θ\) is a solution of this equation if and only if

\[\cos θ(2\cos θ−1)=0. \nonumber \]

Since \(\cos θ=0\) when

\[θ=\dfrac{π}{2},\dfrac{π}{2}±π,\dfrac{π}{2}±2π,…, \nonumber \]

and \(\cos θ=1/2\) when

\[θ=\dfrac{π}{3},\dfrac{π}{3}±2π,…\mathrm{or}\ θ=−\dfrac{π}{3},−\dfrac{π}{3}±2π,…, \nonumber \]

we conclude that the set of solutions to this equation is

\[θ=\dfrac{π}{2}+nπ,\;θ=\dfrac{π}{3}+2nπ \nonumber \]

and

\[θ=−\dfrac{π}{3}+2nπ,\;n=0,±1,±2,….\nonumber \]

b) Using the double-angle formula for \(\sin(2θ)\) and the reciprocal identity for \(\tan(θ)\), the equation can be written as

\[2\sin θ\cos θ=\dfrac{\sin θ}{\cos θ}.\nonumber \]

To solve this equation, we multiply both sides by \(\cos θ\) to eliminate the denominator, and say that if \(θ\) satisfies this equation, then \(θ\) satisfies the equation

\[2\sin θ \cos^2θ−\sin θ=0. \nonumber \]

However, we need to be a little careful here. Even if \(θ\) satisfies this new equation, it may not satisfy the original equation because, to satisfy the original equation, we would need to be able to divide both sides of the equation by \(\cos θ\). However, if \(\cos θ=0\), we cannot divide both sides of the equation by \(\cos θ\). Therefore, it is possible that we may arrive at extraneous solutions. So, at the end, it is important to check for extraneous solutions. Returning to the equation, it is important that we factor \(\sin θ\) out of both terms on the left-hand side instead of dividing both sides of the equation by \(\sin θ\). Factoring the left-hand side of the equation, we can rewrite this equation as

\[\sin θ(2\cos^2θ−1)=0. \nonumber \]

Therefore, the solutions are given by the angles \(θ\) such that \(\sin θ=0\) or \(\cos^2θ=1/2\). The solutions of the first equation are \(θ=0,±π,±2π,….\) The solutions of the second equation are \(θ=π/4,(π/4)±(π/2),(π/4)±π,….\) After checking for extraneous solutions, the set of solutions to the equation is

\[θ=nπ \nonumber \]

and

\[θ=\dfrac{π}{4}+\dfrac{nπ}{2} \nonumber \]

with \(n=0,±1,±2,….\)

Find all solutions to the equation \(\cos(2θ)=\sin θ.\)

- Hint

-

Use the double-angle formula for cosine (Equation \ref{double1}).

- Answer

-

\(θ=\dfrac{3π}{2}+2nπ,\dfrac{π}{6}+2nπ,\dfrac{5π}{6}+2nπ\)

for \(n=0,±1,±2,…\).

Prove the trigonometric identity \(1+\tan^2θ=\sec^2θ.\)

Solution:

We start with the Pythagorean identity (Equation \ref{py1})

\[\sin^2θ+\cos^2θ=1. \nonumber \]

Dividing both sides of this equation by \(\cos^2θ,\) we obtain

\[\dfrac{\sin^2θ}{\cos^2θ}+1=\dfrac{1}{\cos^2θ}. \nonumber \]

Since \(\sin θ/\cos θ=\tan θ\) and \(1/\cos θ=\sec θ\), we conclude that

\[\tan^2θ+1=\sec^2θ. \nonumber \]

Prove the trigonometric identity \(1+\cot^2θ=\csc^2θ.\)

- Answer

-

Divide both sides of the identity \(\sin^2θ+\cos^2θ=1\) by \(\sin^2θ\).

Graphs and Periods of the Trigonometric Functions

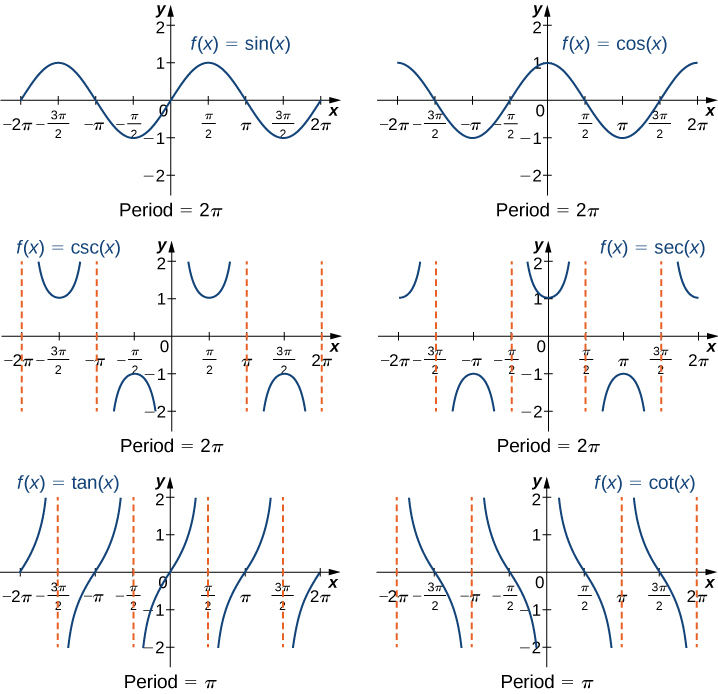

We have seen that as we travel around the unit circle, the values of the trigonometric functions repeat. We can see this pattern in the graphs of the functions. Let \(P=(x,y)\) be a point on the unit circle and let \(θ\) be the corresponding angle . Since the angle \(θ\) and \(θ+2π\) correspond to the same point \(P\), the values of the trigonometric functions at \(θ\) and at \(θ+2π\) are the same. Consequently, the trigonometric functions are periodic functions. The period of a function \(f\) is defined to be the smallest positive value \(p\) such that \(f(x+p)=f(x)\) for all values \(x\) in the domain of \(f\). The sine, cosine, secant, and cosecant functions have a period of \(2π\). Since the tangent and cotangent functions repeat on an interval of length \(π\), their period is \(π\) (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)).

Just as with algebraic functions, we can apply transformations to trigonometric functions. In particular, consider the following function:

\[f(x)=A\sin(B(x−α))+C. \nonumber \]

In Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\), the constant \(α\) causes a horizontal or phase shift. The factor \(B\) changes the period. This transformed sine function will have a period \(2π/|B|\). The factor \(A\) results in a vertical stretch by a factor of \(|A|\). We say \(|A|\) is the “amplitude of \(f\).” The constant \(C\) causes a vertical shift.

Notice in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\) that the graph of \(y=\cos x\) is the graph of \(y=\sin x\) shifted to the left \(π/2\) units. Therefore, we can write

\[\cos x=\sin(x+π/2). \nonumber \]

Similarly, we can view the graph of \(y=\sin x\) as the graph of \(y=\cos x\) shifted right \(π/2\) units, and state that \(\sin x=\cos(x−π/2).\)

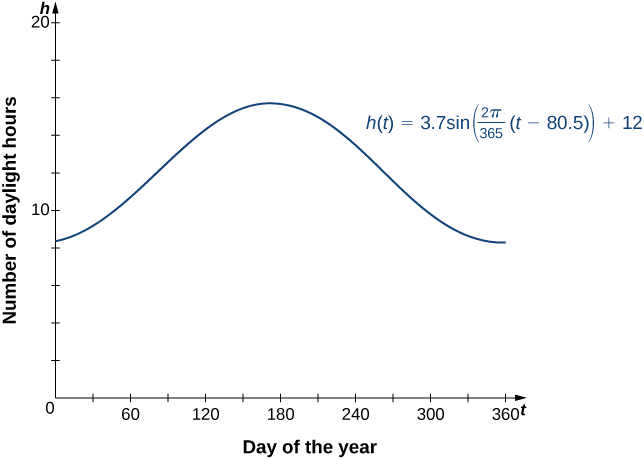

A shifted sine curve arises naturally when graphing the number of hours of daylight in a given location as a function of the day of the year. For example, suppose a city reports that June 21 is the longest day of the year with 15.7 hours and December 21 is the shortest day of the year with 8.3 hours. It can be shown that the function

\[h(t)=3.7\sin \left(\dfrac{2π}{365}(x−80.5)\right)+12 \nonumber \]

is a model for the number of hours of daylight \(h\) as a function of day of the year \(t\) (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)).

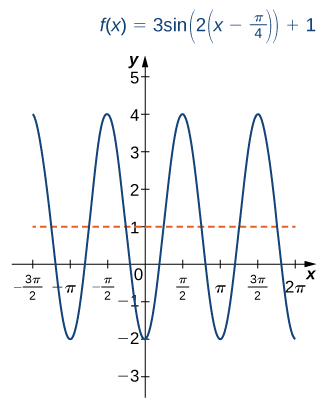

Sketch a graph of \(f(x)=3\sin(2(x−\frac{π}{4}))+1.\)

Solution

This graph is a phase shift of \(y=\sin (x)\) to the right by \(π/4\) units, followed by a horizontal compression by a factor of 2, a vertical stretch by a factor of 3, and then a vertical shift by 1 unit. The period of \(f\) is \(π\).

Describe the relationship between the graph of \(f(x)=3\sin(4x)−5\) and the graph of \(y=\sin(x)\).

- Hint

-

The graph of \(f\) can be sketched using the graph of \(y=\sin(x)\) and a sequence of three transformations.

- Answer

-

To graph \(f(x)=3\sin(4x)−5\), the graph of \(y=\sin(x)\) needs to be compressed horizontally by a factor of 4, then stretched vertically by a factor of 3, then shifted down 5 units. The function \(f\) will have a period of \(π/2\) and an amplitude of 3.

Key Concepts

- Radian measure is defined such that the angle associated with the arc of length 1 on the unit circle has radian measure 1. An angle with a degree measure of \(180\)° has a radian measure of \(\pi\) rad.

- For acute angles \(θ\),the values of the trigonometric functions are defined as ratios of two sides of a right triangle in which one of the acute angles is \(θ\).

- For a general angle \(θ\), let \((x,y)\) be a point on a circle of radius \(r\) corresponding to this angle \(θ\). The trigonometric functions can be written as ratios involving \(x\), \(y\), and \(r\).

- The trigonometric functions are periodic. The sine, cosine, secant, and cosecant functions have period \(2π\). The tangent and cotangent functions have period \(π\).

Key Equations

- Generalized sine function

\(f(x)=A \sin(B(x−α))+C\)

Glossary

- periodic function

- a function is periodic if it has a repeating pattern as the values of \(x\) move from left to right

- radians

- for a circular arc of length \(s\) on a circle of radius 1, the radian measure of the associated angle \(θ\) is \(s\)

- trigonometric functions

- functions of an angle defined as ratios of the lengths of the sides of a right triangle

- trigonometric identity

- an equation involving trigonometric functions that is true for all angles \(θ\) for which the functions in the equation are defined